10 Did the Phoenicians use matres?

According to Naveh (1987:62), there were no matres in early Phoenician inscriptions before the eighth century BC. This is not surprising as such inscriptions were few in Phoenicia. The Phoenician script should have been much more widely used from the eleventh century to the eighth century BC than was attested by the extant scanty inscriptions. We believe that among the Semites, the Phoenicians must have had the greatest need for using matres to write foreign names as they had to make extensive trading contacts with the other Mediterranean peoples. Records of these names were most likely made on papyrus, as it was a most convenient writing material for roving traders. However, it is a perishable material which can hardly survive the passage of time in most climactic conditions, hence the absence of evidence that matres were used to write foreign names in early Phoenician.

We contend that the Phoenicians should have known how to use matres to write foreign names for two reasons. First, the inventors of the first Semitic alphabet must have had a good understanding of the ancient Egyptian writing system, including the use of matres to write foreign names, and so when the need to write foreign names occasionally arose, they would simply do as the Egyptians did. Such knowledge would be passed on from users to learners of the Semitic alphabet and from generation to generation. By the eleventh century BC, the Semites could have been using the method of writing foreign names with matres for several hundred years in Canaan, and this method must have formed part of the Phoenician writing system. The Phoenicians must have found this method indispensable for the writing of foreign names. Second, the genesis of the Greek segmental writing system indirectly supports the hypothesis that the Phoenicians used matres in their writing. One would have great difficulty in explaining the genesis of the Greek alphabet satisfactorily if no Phoenician matres had been available for use in the initial phase of its development (this point will later be elaborated on).

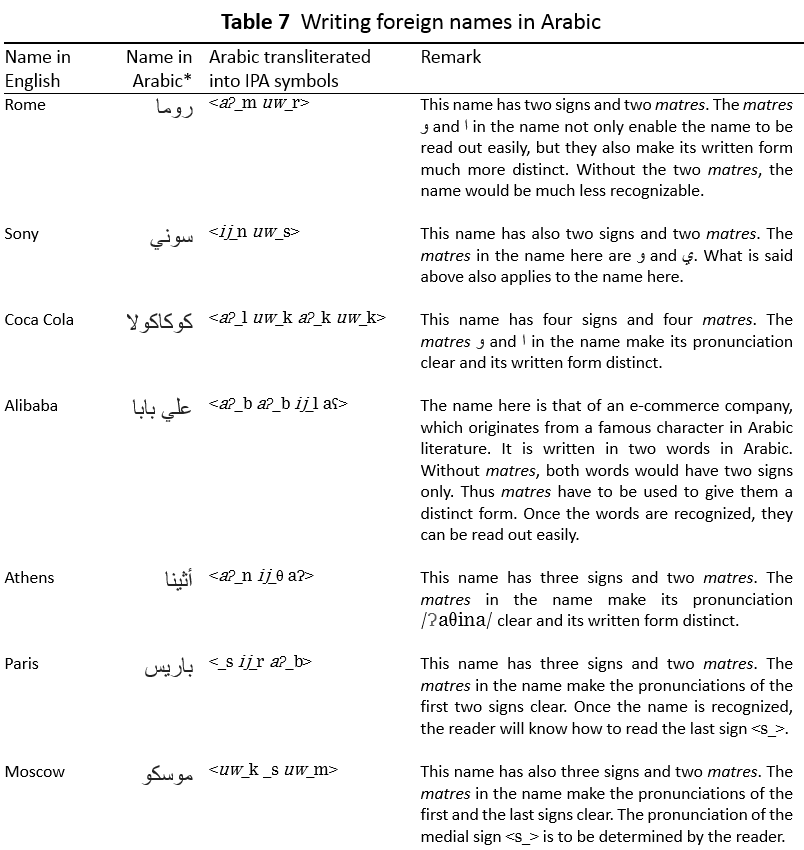

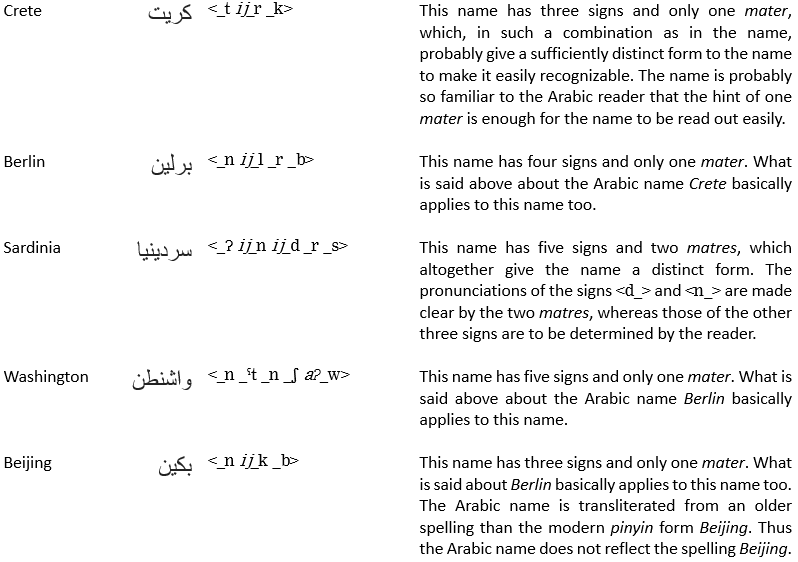

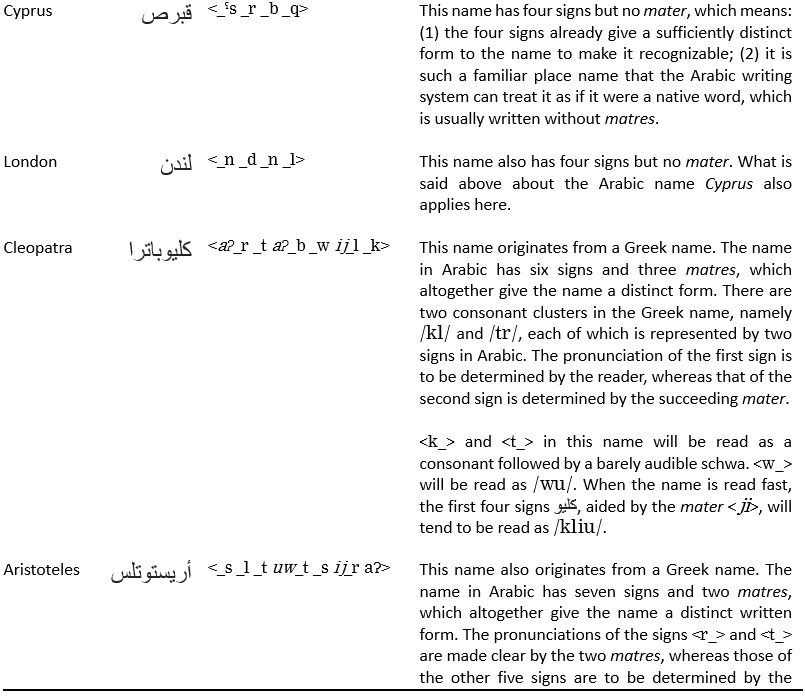

Despite the absence of concrete evidence for the use of matres to write foreign names in early Phoenician, one can still figure out how the Phoenicians would set about writing a foreign name by studying how foreign names are written in ancient Egyptian and in modern Semitic scripts like Arabic and Hebrew. As far as the line of descent of the Phoenician script is concerned, Egyptian is its predecessor while Arabic and Hebrew are its successors. By studying the way in which foreign names from both ends are written, one can probably form an idea of how the Phoenicians would write a foreign name. We have already examined by means of a few specific examples in §8.3 the Egyptian way of writing foreign names. We are going to study some more examples in modern Arabic, which, we believe, is a suitable choice among the Semitic alphabetic writings as its method of writing foreign names is based on the use of three matres like that of Egyptian and presumably that of Phoenician too. Table 7 below shows how foreign names are written in Arabic. Please note that the transliterations here should be read from right to left in accordance with the direction of Arabic writing.

Today the Arabic script is generally regarded as consonantal writing. Each Arabic sign or letter is taken to be a consonant letter. For example, in the name روما ‘Rome’, which is generally transliterated as <ruma>, the signs ر and ﻤ are seen as consonant letters that represent /r/ and /m/, whereas the matres و and ا are seen as vowel letters that represent /u(:)/ and /a(:)/. However, to regard the Arabic writing as consonantal is questionable for two reasons. First, the sound of a mater in Arabic is not a vowel; it is always a CV syllable. The silent matres و and ا should be read as /wu/ and /Ɂa/, not /u/ and /a/. Second, native Arabic words are usually written without matres. If the Arabic signs were consonant letters, these words would not be easily pronounced. But the fact is that they are perfectly pronounceable. This means that an Arabic sign is not of the same nature as a consonant letter in a segmental writing system like English. All Arabic words, written with or without matres, are pronounceable. Even a foreign name written without matres, such as لندن ‘London’, is pronounceable. The letters <L, n, d, n> in the English word <London> are bona fide consonant letters whereas the signs <ﻠ, ﻧ, د, ن > in the Arabic word <لندن> are not. An English consonant letter represents a sound that usually has to be brought out by sounding together with that of a vowel letter, while an Arabic sign represents several CV syllables which can be read out easily.

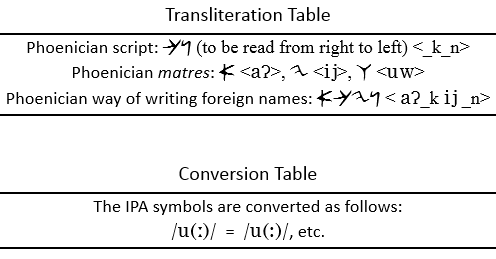

Foreign names written in Egyptian or Arabic are typically transliterations of names written in a foreign script. However, when the Phoenicians tried to write a Greek name in their trading contacts with the Greeks, they would not have a written form of the name to rely on. To record the name, they could only resort to the sound of the name actually spoken by native speakers. Owing to the nature of the Phoenician script, the Phoenicians would come to realize that the Greek names had better be written with the aid of matres. For example, if they wrote down the Greek name /nika:/ simply as <_k_n> (to be read from right to left) /n_ k_/, then they might not be able to recall how it should be read at a later time since <_k_n> could be read in a great number of ways. To give a definite reading to the name, they could simply follow the Egyptians’ method of writing foreign names with matres.

The Phoenician signs <_Ɂ>, <_j>, and <_w>, we believe, can be used as matres to disambiguate the reading of a foreign name, apart from functioning normally like the other Phoenician signs. The Phoenician matres, we also believe, are only three in number because of their Egyptian origin. When used as matres, the signs <_Ɂ>, <_j>, and <_w> would be read as /Ɂa/, /ji/, and /wu/ respectively. Since an ordinary Phoenician sign has multiple sound values, a mater is placed after it so as to specify its sound value in the writing of a foreign name. The mater requires the preceding sign to rhyme with it. It should be noted, however, that a mater is a syllable indicator only. It is a silent letter which does not represent any part of the preceding sign’s sound. To write the Greek name /nika:/, the Phoenicians would use the most suitable matres after <_n> and <_k> to specify their sound value. How the Phoenicians would write a Greek name depends on not only their writing system, but also their perception of the actual Greek pronunciation of the name. It goes without saying that the Phoenicians’ perception of the Greek sounds was affected to a large extent by their mother tongue. The Phoenicians would probably write the name as <aɁ_k ij _n>. Since <_n> /n_/ should rhyme with <ij> /ji/, and <_k> /k_/ with <aɁ> /Ɂa/, the written name <aɁ_k ij _n> would be read as /nika:/. The Phoenicians should be happy with writing the Greek name /nika:/ as <aɁ_k ij _n>, because to them there seemed to be little difference between the Greeks’ pronunciation of the name and their way of reading the written name.

8 January 2017

Views: 364