7 The nature of ancient Egyptian writing

(Revised on 12 September 2019)

To understand the nature of Egyptian writing, one must first understand the nature of the Egyptian language because the two are closely related to each other. The ancient Egyptian language and the Semitic languages belong to the Afro-Asiatic language family. As explained in §4, the basic syllable structure of the Semitic languages is cα. The basic syllable structure of the ancient Egyptian language should also be the same. By adhering to this basic yet flexible syllable structure cα, native speakers of the Egyptian language could easily form derivative or inflectional words according to a simple principle. Our analysis of the syllable structure of ancient Egyptian in terms of cα is basically consistent with Loprieno’s (1995:36). Generally speaking, the phonological structure of an ancient Egyptian word is either c1α1, or c1α1c2α2, or c1α1c2α2c3α3. As early as five thousand years ago, the ancient Egyptians were able to write their language word by word either in pictorial signs called hieroglyphs or in a cursive or linear form of hieroglyphic writing called hieratic.

7.1 The Egyptian logograms

Egyptian hieroglyphs are used in monumental inscriptions. They are classified by scholars broadly into three types: logograms, phonograms, and determinatives (Davies 1987:30; Coulmas 2003:173). A logogram generally represents a common Egyptian noun whose pronunciation may vary with its case (this point will be elaborated below). The noun that a logogram represents generally refers to a common object or a living thing that could often be seen in the Egyptians’ daily lives. So an Egyptian logogram is a word sign, which is a conventionalized pictogram that represents a whole spoken word. It is a motivated sign because its shape is related to the sense of the spoken word that it stands for. For example, the logogram <t_>, depicting a loaf, represents the spoken word for ‘loaf’ in Egyptian. As a spoken word has both sense and sound, a logogram created to stand for an Egyptian word perforce carries, besides its sense, its sound values. The logogram <t_> therefore carries not only the sense ‘loaf’ but also the sound of the Egyptian word it stands for, namely /t_/. It should be noted that this spoken word has multiple sound values even though it has the simple phonological structure of c1α1, and so when its logogram <t_> is used as a phonogram through rebus, it also carries the multiple sound values of the spoken word /t_/ ‘loaf’. As a matter of fact, <t_> stands for several syllables related by an unvarying onset c1 followed by variable rhymes α1.

7.2 The Egyptian phonograms

Ancient Egyptian has a simple syllable structure (cα) and only a few vowels. Linguists are generally agreed that there were six vowels in archaic or old Egyptian: /a/, /i/, /u/, /a:/, /i:/, /u:/ (Loprieno 1995:35). Another way to describe the Egyptian vocalic system is that it had three vowels: /a/, /i/, /u/, each of which could be either long or short (Davies 1987:37). As it is generally presumed that ancient Egyptian had 23 or 24 consonants, there were at most: 24 c × 6 α = 144 cα syllables in the language (excluding those weakened cα syllables in which α had almost disappeared). As was said earlier, the phonological structure of an ancient Egyptian word is generally c1α1, c1α1c2α2, or c1α1c2α2c3α3. Discounting those weakened cα syllables in which α had almost disappeared, the ancient Egyptians could, in theory, create at most: (a) 144 words with the phonological structure of c1α1 (24 × 6 = 144); (b) 20,736 words with the phonological structure of c1α1c2α2 (24 × 6 × 24 × 6 = 20,736); (c) 2,985,984 words with the phonological structure of c1α1c2α2c3α3 (24 × 6 × 24 × 6 × 24 × 6 = 2,985,984). Each of the words thus created would be different in pronunciation. But in practice the ancient Egyptians would not exhaust all the possible sound combinations in their language in creating words because there was no such need. In fact, among all the words created by the ancient Egyptians, some would turn out to be, quite naturally, homophonous, just as in any other language.

When the ancient Egyptians had difficulty in creating a sign to represent a word whose sense is too abstract to be easily represented by a pictogram, they would be obliged to resort to the use of the rebus principle by borrowing a homophonous logogram to represent it. In fact, as can be seen from how Egyptian words are written in the ancient Egyptian script, many logograms are often used as phonograms, including those logograms with the phonological structures of c1α1c2α2 and c1α1c2α2c3α3. It goes without saying, however, that logograms with the phonological structure of c1α1 are used the most frequently as phonograms because phonograms of this kind are the most convenient, flexible, and versatile.

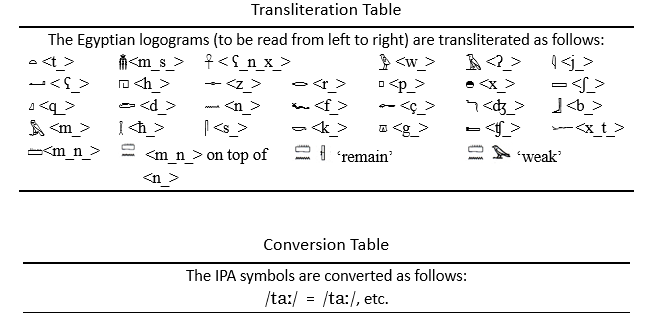

Approximately 750 logograms were used in the second millennium BC for the classical language of ancient Egyptian (Loprieno 1995:12). About 170 of them could also be used through rebus as phonograms to represent the sounds of homophonous words. For example, the three logograms <t_>, <m_s_> and <ʕ_n_x_>, originally used to represent the words /t_/ ‘loaf’, /m_s_/ ‘fox fur’, and /ʕ_n_x_/ ‘sandal strap’ respectively, were also used as phonograms to represent the homophonous words or morphemes /t_/ ‘feminine gender’, /m_s_/ ‘to give birth to’, and /ʕ_n_x_/ ‘life’. These three types of phonograms are generally called monoconsonantal, biconsonantal, and triconsonantal signs respectively (Davies 1987:32; Loprieno 1995:12). Since a phonogram was borrowed from a logogram through rebus, the former would naturally have as many sound values as the latter. If an Egyptian logogram had multiple sound values, then the phonogram derived from it would have multiple sound values.

To call an Egyptian phonogram “consonantal” is to call attention to its consonantal sounds, which are the unvarying elements of a phonogram whichever way the phonogram is pronounced. By counting the number of these unvarying consonants, one can divide the Egyptian phonograms conveniently and neatly into three types. Today these three types of phonograms are conventionally transliterated as <c1>, <c1c2>, and <c1c2c3>, which obviously cannot be easily pronounced. For the phonograms to be pronounceable, the vowel after c, if any, has to be supplied by the reader according to the context in which the phonograms are found. A fuller form of transliteration would be <c1α1>, <c1α1c2α2>, and <c1α1c2α2c3α3>. A phonogram that stands for c1α1 here would be regarded by the ancient Egyptians as representing several “sounds”, each of which was a single integral sound unit. However, this kind of phonogram is generally introduced today as a monoconsonantal sign which represents several CV syllables in which V could vary or even disappear at times.

Of the three types of Egyptian phonograms, the most noteworthy are the monoconsonantal signs. It is generally believed that the Egyptian monoconsonantal signs most probably inspired the creation of the first Semitic alphabet. Thus a good understanding of the Egyptian monoconsonantal signs is of paramount importance. The better we can understand the nature of this type of signs, the better we know how the first Semitic alphabet came into being.

7.2.1 Why has an Egyptian logogram multiple sound values?

As explained earlier, the logogram <t_> for ‘loaf’ can be used as a phonogram through rebus. The sound values of the phonogram <t_> are quite certain, as it most probably represents /t/ followed by any vowel in the Egyptian vocalic system (the notation we use in this treatise is /t_/). As ancient Egyptian has six vowels: /a/, /i/, /u/, /a:/, /i:/, /u:/, the phonogram <t_> most probably represents /ta/, /ti/, /tu/, /ta:/, /ti:/, and /tu:/.[1] What needs explaining is why the phonogram <t_> can assume these sound values.

A brief explanation is that the logogram <t_>, from which the phonogram <t_> is borrowed through rebus, has multiple sound values. The logogram <t_> has multiple sound values because the noun it represents has multiple sound values. The Egyptian noun for ‘loaf’, we believe, is spoken as /ta:/, /ti:/, or /tu:/. Each syllable is likely to be long rather than short, for it represents possibly a fusion of a lexical morpheme and a grammatical morpheme.[2] The lexical morpheme for ‘loaf’ is spoken possibly as /t_/, and the case morpheme for ‘accusative’, ‘genitive’, and ‘nominative’ is spoken possibly as /-a/, /-i/, or /-u/. When the lexical morpheme is fused with the succeeding case-ending vowel to form the Egyptian noun for ‘loaf’, the noun is spoken as /ta:/, /ti:/, or /tu:/. Its pronunciation varies with its grammatical case in a sentence.[3] The logogram <t_> that represents the Egyptian noun for ‘loaf’ is thus read as /ta:/, /ti:/, or /tu:/. When the sign <t_> is used through rebus as a phonogram, it can obviously represent /ta:/, /ti:/, /tu:/. The method of rebus, however, allows the phonogram <t_> to represent a syllable in any spoken word that has the same onset and rhyme as the spoken word /t_/ ‘loaf’, irrespective of vowel length; that is, the phonogram <t_> can also represent /ta/, /ti/, /tu/, apart from /ta:/, /ti:/, /tu:/.

The Egyptian logogram <t_> for ‘loaf’ probably represents a masculine noun as it is never followed by the feminine gender marker. When it has no written suffix to signify its number, it should stand for a singular noun. If this singular Egyptian noun /t_/ ‘loaf’ had no grammatical case to signify, it would be spoken as a single syllable only, not three. The Egyptian logogram <t_> that stands for the noun /t_/ ‘loaf’ would then have a single reading, and when used as a phonogram through rebus, the phonogram <t_> would have a single reading too, not several. However, the phonogram <t_> does have several readings. This indirectly shows that the Egyptian logogram <t_>, from which the phonogram <t_> is borrowed, has several readings. The logogram <t_> has several readings because the noun that <t_> represents has pronunciations that vary with its grammatical case. This is also the reason why we believe that an Egyptian noun is inflected for case, just like an Akkadian or Ugaritic noun. The final part of a noun and the case-ending vowel seem to have fused together in ancient Egyptian. A logogram that stands for a noun perforce carries the pronunciations that vary with the cases. The phonogram that is borrowed from a logogram therefore also has various pronunciations.

7.2.2 The creation of the Egyptian monoconsonantal signs

We know from the Egyptian script that the monoconsonantal signs <w_> and <t_> are generally used after a logogram to write respectively the plural number and the feminine gender of an Egyptian noun. When a logogram is not followed by these signs, it can be assumed that the logogram probably represents a singular and masculine noun. The way in which the logogram <t_> is written and pronounced indicates that it probably stands for a singular and masculine noun. We believe that the ancient Egyptians would search among the logograms for those which represent a singular and masculine noun that is pronounced as cα, because these logograms could then be used as phonograms through rebus in a straightforward manner. Judging from the list of Egyptian monoconsonantal signs in Figure 80 of G. R. Driver’s Semitic Writing (1948:135), the ancient Egyptians seem to have found six such signs in this way: <ʔ_> /ʔ_/, <j_> /j_/, <ʕ_> /ʕ_/, <h_> /h_/, <z_> /z_/, <t_> /t_/. Each sign represents six syllables, as explained at the beginning of this section. It seems that there are not many monoconsonantal nouns that refer to common objects or living things in the Egyptian language.

How would the ancient Egyptians write the other cα syllables in their language, such as the syllable for the preposition meaning ‘towards’? We know from the Egyptian script that this preposition begins with /r/ and ends with a vowel. As prepositions are most unlikely to be inflected in their pronunciations, we believe that the Egyptian preposition for ‘towards’ is read as /r/ followed by a definite vowel. The ancient Egyptians would look for a suitable logogram that could be used as a phonogram through rebus to represent this sound. If they had difficulty in finding a monoconsonantal logogram for this purpose, they would resort to a biconsonantal or even triconsonantal one. In theory, they could choose any logogram whose first syllable is the same as the pronunciation of the preposition ‘towards’ and use it as a phonogram to represent, apart from the pronunciation of the preposition ‘towards’, /r/ followed by any vowel, i.e. /r_/. But judging from the monoconsonantal phonograms that the Egyptians finally used, as listed in G. R. Driver’s Figure 80 mentioned above, they seemed to prefer logograms that begin with a strong syllable and end with one or even two weak syllables. For example, they finally chose the logogram <r_> for ‘mouth’ and used it as a phonogram for writing the preposition ‘towards’. The logogram <r_> is read as /r_ʔ_/ or as /r_j_/. The first syllable /r_/ is probably both prominent and fixed, and is perhaps the same as the sound of the preposition ‘towards’. It is possible, however, that the Egyptian noun for ‘mouth’ can also be spoken informally simply as /r_/ when the weaker syllable /ʔ_/ or /j_/ is assimilated to the preceding stronger syllable /r_/ (see footnote 5). If that is so, the remaining or surviving /r_/ should be inflected for case. The logogram <r_> that represents the surviving /r_/ can thus be read as /ra:/, /ri:/, /ru:/. The logogram <r_> then has multiple sound values, hence the phonogram <r_>. The ancient Egyptians might have found, in accordance with this principle, the following five monoconsonantal signs: <r_> /r_/ < /r_ʔ_/ or /r_j_/, <p_> /p_/ < /p_j_/, <x_> /x_/ < /x_j_/, <ʃ_> /ʃ_/ < /ʃ_ʔ_j_/, <q_> /q_/ < /q_ʔ_ʔ_/.

However, two monoconsonantal signs <d_> and <ʤ_> seem to have originated from logograms in different ways. The hand logogram <d_> is read as /j_d_/. It is possible that the first syllable /j_/ is weak or unstressed whereas the second syllable /d_/ is strong or stressed. If this is the case, as the final part of a noun and the case-ending vowel were probably fused together in Egyptian, the noun for ‘hand’ might be read as /j_da:/, /j_di:/, or /j_du:/. Since the first syllable /j_/ is weak, it is possible that the noun for ‘hand’ could be spoken informally as /da:/, /di:/, or /du:/ when the meaning of this sound is clear in the context. Thus the logogram <d_> for ‘hand’ might also be read simply as /da:/, /di:/, or /du:/, depending on its case. The logogram <d_> could then be used through rebus as a phonogram with multiple sound values. How the cobra logogram <ʤ_> turned into a phonogram is more complicated, as it seems to represent a feminine noun whose gender needs to be indicated in writing as well. Four monoconsonantal signs <ʤ_>, <f_>, <n_>, and <ç_> seem to have originated from logograms that represent feminine nouns. We now try to explain how these logograms came to be used as phonograms.

We start with the logogram <n_> for ‘water’. The Egyptian noun for ‘water’ is spoken as /n_t_/. One can regard this noun as consisting of the base /n_/, which conveys the lexical meaning ‘water’, plus the ending /t_/, which signifies ‘the feminine gender’. The noun /n_t_/ ‘water’ is written as <n_> on top of <t_>. <n_> is a logogram depicting rippling water, while <t_> is a monoconsonantal sign that indicates ‘the feminine gender’ /t_/. As <t_> represents the /t_/ in /n_t_/, the water logogram <n_> can then be regarded as representing /n_/. In theory, the Egyptian case-ending vowels can be suffixed either to the noun base /n_/ or to the feminine gender marker /t_/. In the former case, the case-ending vowels will be fused together with the base. The /n_/ of /n_t_/ will probably be spoken as /na:/, /ni:/, or /nu:/, depending on the case of the noun in a sentence. When the logogram <n_> that represents /na:/, /ni:/, or /nu:/ is used as a phonogram through rebus, the phonogram <n_> will obviously have multiple sound values.

However, judging from how case endings are suffixed to the feminine gender marker /t/ in both Akkadian and Ugaritic, we think it much more likely that the case-ending vowels in ancient Egyptian are likewise suffixed to and fused with the /t_/ sound for ‘the feminine gender’. If that is so, the /t_/ in /n_t_/ will likely be inflected for case, and the sound of the base /n_/ will probably be both prominent and fixed, like that of the base of a noun in Akkadian and Ugaritic. In other words, the base /n_/ will probably be spoken as /n/ plus a definite vowel. The logogram <n_> will then represent /n/ plus a definite vowel, i.e. a single CV syllable, and the phonogram derived from it will likewise represent a single CV syllable. This kind of phonogram that represents a single CV syllable will be distinct from the other phonograms that have multiple sound values, such as <t_>, which basically represents six CV syllables. Four phonograms representing a single CV syllable seem to have derived from logograms in this way: <n_> /nV/ < /nVt _/, <f_> /fV/ < /fVt_/, <ç_> /çV/ < /çVt_/, <ʤ_> /ʤV/ < /w_ʔ_ʤVt _/.

We believe that the above four phonograms eventually changed from syllabograms with a single sound value into monoconsonantal signs with multiple sound values, possibly after a period of trial and error during which these two kinds of phonograms were in use to write different Egyptian words. The monoconsonantal signs with multiple sound values eventually prevailed probably because they are more appropriate for representing the Egyptian language than the syllabograms with a single sound value. To understand this point, one has to look into the morphological structure of a noun or a verb used in ancient Egyptian and Semitic languages. As was said earlier, the phonological structure of such a noun or verb is c1α1, c1α1c2α2, or c1α1c2α2c3α3. Take for example a noun or a verb with the most common structure of c1α1c2α2c3α3. It can be analysed as consisting of a lexical root c1_c2_c3_, which is a sequence of three consonants used for conveying the lexical core meaning, and a pattern _α1_α2_α3, which is a sequence of variable vowels interdigitating with the sequence of unvarying consonants to convey the grammatical or derived meanings. If monoconsonantal signs with multiple sound values are used to write such a noun or verb, it will be represented by an unvarying sequence of three signs, from which one can easily identify the skeletal structure of a written noun or verb and then grasp its lexical core meaning. However, if syllabograms with a single sound value, like Akkadian syllabograms or Japanese kana, are used to write such a noun or verb, it will be represented by a sequence of three syllabograms which may vary with the change of grammatical or derived meanings. As a result, the same noun or verb may be written in completely different combinations of syllabograms and so one cannot easily identify the written noun or verb from a glance at the sequence of the three syllabograms.

In ancient Egyptian writing, if the phonogram <n_> represented a single CV syllable, it would not be as versatile as a phonogram that represented several CV syllables with the same onset. One might wonder why the Egyptian scribes did not find another logogram that could be read as /na(:)/, /ni(:)/, /nu(:)/ to replace the phonogram <n_>. The answer might have something to do with the fact that this logogram was not easy to find. If that is so, the Egyptian scribes would be obliged to see whether they could use the phonogram <n_> as if it was a phonogram with multiple sound values, just like <t_>, <r_>, <d_>, etc. If <n_> could actually work as a phonogram with multiple sound values, as it most likely could, they could then convert it into a phonogram with multiple sound values. The ancient Egyptians did end up using <n_> as a phonogram with multiple sound values. We believe that they might have found the following monoconsonantal signs in a similar way: <n_> /n_/, <f_> /f_/, <ç_> /ç_/, <ʤ_> /ʤ_/. Each sign stands for six syllables. The Egyptian method of creating these phonograms in the above way might have inspired the Semites to create their own alphabet in the first half of the second millennium BC. This point will be elaborated on when the creation of the Semitic alphabet is discussed.

According to G. R. Driver (1948:135), there is no way of telling precisely how some phonograms are derived from logograms through rebus, as the way in which these logograms are read remains unknown. Hence, the origin of some phonograms remains obscure. These phonograms are: <w_> /w_/, <b_> /b_/, <m_> /m_/, <ħ_> /ħ_/., <s_> /s_/, <k_> /k_/, <g_> /g_/, <ʧ_> /ʧ_/.

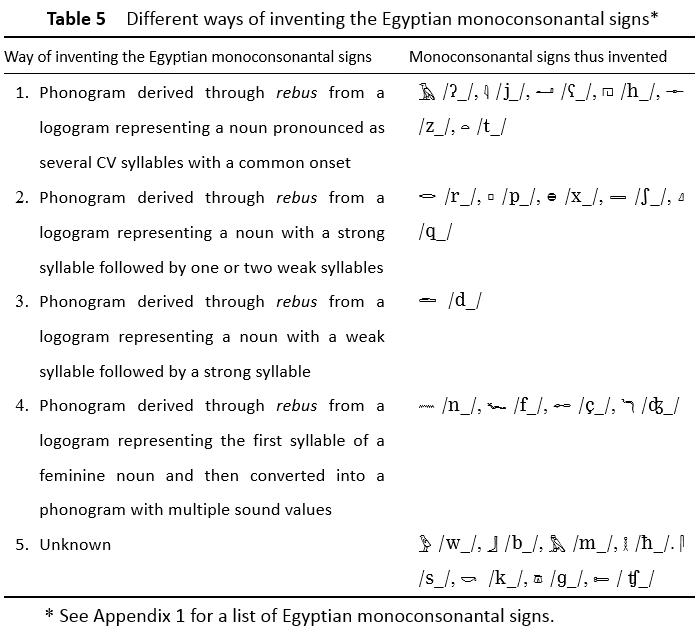

The Egyptian monoconsonantal signs seem to have arisen naturally from the evolution of the Egyptian script. To represent a monosyllabic function word whose sense is too abstract for easy graphic representation, the ancient Egyptians would be obliged to turn a logogram into a phonogram through rebus. They would search among the logograms for those which represent a noun with the c1α1 phonological structure. They managed to find only a few such logograms, as the Egyptian nouns that refer to physical objects are generally disyllabic or polysyllabic. Thus the ancient Egyptians had to resort to those logograms that are characterized by having a strong syllable and one or two weak syllables. These weak syllables begin with the so-called weak consonants and so can easily be elided or assimilated. The Egyptians ended up using about twenty-five logograms as monoconsonantal signs. The different ways in which these signs came into being can be summarized in the table below:

An Egyptian monoconsonantal sign is generally introduced as a phonogram that represents a consonant. It is often said, for example, that the phonogram <t_> represents the consonant /t/. We believe that the concept of consonant would be alien to the ancient Egyptians. To them, the phonogram <t_> had several concrete and pronounceable sounds, which can be transcribed today as /ta/, /ti/, /tu/, /ta:/, /ti:/, /tu:/. When weakened, the Egyptian syllables /ta/, /ti/, /tu/ might be realized respectively as [tɐ], [tɪ], [tʊ], or generally as a further weakened [tə] or [t], just as the Phoenician syllables /ba/, /bi/, /bu/ might be realized respectively as [bɐ], [bɪ], [bʊ], or generally as a further weakened [bə] or [b] (see Table 2). In whichever way the above Egyptian syllables are pronounced, they can be represented by the same phonogram <t_>. Even when they are pronounced as the minimal sound [t], they can be similarly represented. The phonogram <t_>, in isolation, represents six full syllables, but in a piece of writing it represents either a full syllable or a weakened one. Hence the Egyptian monoconsonantal signs are in essence syllabic, not consonantal.

To put it more simply, the phonogram <t_> can be regarded as representing three basic sounds /ta/, /ti/, and /tu/. These sounds can be lengthened or shortened. When lengthened, they become /ta:/, /ti:/, and /tu:/. When shortened, they become /t/.

Although it seems justified to call the Egyptian phonograms mono-, bi- and tri-consonantal signs, it should be noted that the Egyptian scribes would not see their phonograms as consonantal signs simply because they had no concept of consonant. They would regard each phonogram simply as a sign that could be pronounced in a number of ways. Normally they would not take the trouble to analyse the pronunciation of a phonogram. If they had to do so, they would probably break it up into syllables. To say that an Egyptian phonogram records only the unvarying consonant(s) while ignoring the variable vowels is to ‘falsify essentially the Egyptians’ own experience of writing in order to understand it’ (Powell 2009:164).

To the Egyptians, it might be quite natural for a phonogram to have multiple sound values. Such phonograms would not pose much of a problem for the Egyptians, as they would not read an Egyptian word phonogram by phonogram, just as we would not read an English word letter by letter. When the Egyptians read, they would take in the shape of the word as a whole. Once they recognized a written word in a context, they, guided by their mother tongue, would automatically know how to read it.

7.2.3 How phonograms function in Egyptian writing

How did the Egyptians use their phonograms? To write the sound of a c1α1 word, an Egyptian could use a monoconsonantal sign, as in the case of using the phonogram <r_> /r_/ for the word /r_/ ‘to’. To write the sound of a c1α1c2α2 word, an Egyptian could use either two monoconsonantal signs, as in the case of using the phonograms <r_> /r_/ and <n_> /n_/ for the word /r_n_/ ‘name’, or a single biconsonantal sign, as in the case of using <m_s_> /m_s_/ for the word /m_s_/ ‘to give birth to’. A monoconsonantal sign <s_> /s_/ was added to <m_s_> as a phonetic complement, not only to give an extra hint to the last part of the pronunciation of the word, but also to give the word a more distinctive written form. It should be noted that a phonetic complement is a sound indicator only and is silent in the written word. To write a c1α1c2α2c3α3 word, an Egyptian could use either three monoconsonantal signs, or a monoconsonantal sign plus a biconsonantal sign, or a single triconsonantal sign. For example, to write the word /n_x_t_/ ‘strong’, the Egyptians conventionally used the monoconsonantal sign <n_> /n_/ plus the biconsonantal sign <x_t_> /x_ t_/.

7.3 The Egyptian determinatives

To use phonograms alone to represent words with the same phonological structure c1α1, c1α1c2α2, or c1α1c2α2c3α3 may not be sufficient to disambiguate their meanings. Thus sometimes there is a need to add determinatives to phonograms to clarify their meanings. For example, the Egyptian words meaning ‘remain’ and ‘weak’ are both pronounced /m_n_/, written as <m_n_> on top of <n_>, <m_n_> being the biconsonantal phonogram for /m_n_/ and <n_> being a complementary phonogram for /n_/. The Egyptians added the determinatives <book-roll> and <small bird> to clarify the meanings of the two words with the same phonological structure c1α1c2α2: {remain} represented by <m_n_> on top of <n_> + determinative <book-roll>, and {weak} represented by <m_n_> on top of <n_> + determinative <small bird>. The <book-roll> signifies an abstract notion, whereas the <small bird> signifies something weak. It is worth noting that determinatives are semantic indicators only and do not carry any sound values.

7.4 The signs used in ancient Egyptian writing: a summary

To sum up, ancient Egyptian writing has three kinds of signs: logograms, phonograms, and determinatives. Logograms can be regarded as the basic signs because all phonograms and determinatives are derived from logograms. To write an Egyptian word, an Egyptian scribe had a large repertoire of signs at his disposal. He could use a single sign, which is either a logogram or a phonogram. Or he could use a combination of signs, which can vary in both kind and number. This enabled the Egyptians to create a rich variety of word forms that enhanced legibility. The pronunciation of each written noun or verb in ancient Egyptian varied with its grammatical meanings, while its written form might remain unchanged. However, this did not bother the Egyptians, because once they recognized its written form and grasped the meaning from its context, they knew how to read it. The reading of foreign names, however, was quite another matter because the context was of little help.

[1] It should be noted that the three basic Egyptian syllables /ta/, /ti/, and /tu/, when weakened, can be realized as [t]. See Table 2, which shows that the three basic Phoenician syllables /ba/, /bi/, and /bu/ can be realized as a weakened [b].

[2] An Egyptian syllable with a long vowel could have evolved from the c1α1c2α2 structure, in which c2 is a so-called weak consonant and α2 is a short vowel. When the weaker c2α2 is assimilated to the stronger c1α1, the two syllables coalesce into a syllable with a long vowel.

[3] The Egyptian noun for ‘loaf’ is spoken as /ta:/, /ti:/, and /tu:/, just as the Ugaritic and Akkadian noun for ‘mouth’ is spoken as /pa:/ (accusative), /pi:/ (genitive), and /pu:/ (nominative). About the pronunciations of the Ugaritic and Akkadian noun for ‘mouth’, see Gordon (1965:57).

27 December 2016

Views: 581