4 The nature of a Phoenician sign

Today one can study directly how the modern Arabic and Hebrew scripts relate to their spoken languages and how their letters are pronounced in a piece of writing. Since the above scripts are descended from Phoenician writing through Aramaic without structural modification, the inner structure of all these Semitic alphabetic scripts should be the same, just as the inner structure of the Greek, Etruscan, Latin, and English alphabetic scripts is the same. A Phoenician sign should thus be of the same nature as an Arabic or Hebrew letter: it is basically a syllabic sign with multiple sound values. The written form ﻛﺘﺐ of the Arabic word /kataba/ ‘he wrote’ can be used as an example to illustrate the nature of an Arabic sign. It comprises three signs: ﻛ + ﺘ + ﺐ, written from right to left. ﻛ stands for /ka/, ﺘ for /ta/, and ﺐ for /ba/. When ﻛﺘﺐ means ‘he wrote’, the signs ﺘ ,ﻛ, and ﺐ are clearly syllabic. The same written form ﻛﺘﺐ can also be read as /kutub/, meaning ‘books’. It can be seen from this example that the signs ﺘ ,ﻛ, and ﺐ have other sound values apart from /ka/, /ta/, and /ba/.

One might argue that ﺐ is a consonantal sign when ﻛﺘﺐ is read as /kutub/, because ﺐ stands for /b/. However, we contend that ﺐ can still be regarded as a syllabic sign representing a syllable whose last part has weakened and finally disappeared. The /b/ in /kutub/ can be regarded as originating from a weakened syllable: /ba/, /bi/ or /bu/. This syllable has become so weakened and short that it is now ordinarily spoken as [b]. If this way of analysing the /b/ of /kutub/ can be established, we can put it more generally by saying that the final consonant of a closed Arabic syllable can be regarded as originating from a short syllable whose last part has weakened. An Arabic letter can then be regarded as a sign representing several syllables which have a common basic structure that can be represented by cα, where c stands for an unvarying consonant and α for a variable vowel. When α is short, it can become so weak and short that it can be regarded as non-existent. If all the Arabic letters are regarded as representing cα, then the phonological structure of Arabic words can be analysed in terms of cα syllables only.

Our analysis of the Arabic syllable is based on the hypothesis that the Semitic CVC syllable can be analysed as deriving, historically or even prehistorically, from two syllables: CV + CV. The evolution from CVCV to CVC is a main form of development in the Semitic languages and is beneficial in many ways to the development of the Semitic languages as systems of communication. According to Sáenz-Badillos, a professor of Hebrew, by 1365 BC the disappearance of case-ending vowels and the development of the verb pattern qatala occurred in some Canaanite dialects, and prior to the ninth century BC, the loss of word-final short vowels took place (1993:45). These are all cases of evolution from CVCV to CVC.[1] Take for example the evolution from qatala to qatal. The shift took place probably because qatal required less effort to speak than qatala. A language community is a kind of “phonetic laboratory”. One factor affecting phonetic change is the constant tug-of-war between the speaker’s tendency to make the least effort possible in communication and the listener’s demand for intelligibility. The development of the verb pattern from qatala to qatal must have gone through a long period of experimentation to make sure that the effectiveness of communication was not adversely affected before the verb pattern settled on qatal. As a matter of fact, the shift from CVCV to CVC or vice versa is not uncommon in the Semitic languages. For example, the Arabic word meaning ‘you are writing’ can be spoken either as /taktubu/ or as /taktub/. The last CVCV /-tubu/ can become CVC /-tub/, or vice versa.

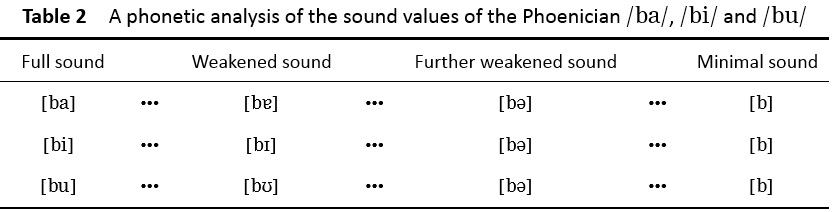

As Phoenician is a Canaanite dialect, its CVC structure can be said to have derived from CVCV (CV stands for a weakened CV). A Phoenician sign stands generally for CV and occasionally for CV. If a Phoenician sign can be seen as a sign representing several CV syllables, including those which have weakened to CV, then the twenty-two Phoenician signs can easily write out all the “sounds” of the Phoenician language. To the Phoenicians, a Phoenician sign stood for several “sounds” which they felt were somehow related both semantically and phonologically. These “sounds”, including those weakened syllables CV, would be regarded as belonging to the same category. The weakened syllables CV would not be regarded as belonging to a separate category, as all the CV syllables will have a chance to turn into CV in their spoken language when V is a short vowel. That is to say, the short Phoenician syllables, say, /ba/, /bi/ and /bu/, might be read as [bɐ], [bɪ], and [bʊ] respectively, or generally as [bə] or [b] in everyday speech as the Phoenician language evolved. Table 2 below shows a phonetic analysis of the sound values of the Phoenician syllables /ba/, /bi/ and /bu/:

The Phoenician syllable /ba/ is here used as an example to illustrate how the Phoenicians would regard the sound values of their basic syllables. What is said about /ba/ applies to /bi/ and to /bu/. When the Phoenician syllable /ba/ is spoken, its sound can vary in length and in accentuation as the actual conversational situation demands. These sounds may range from a fully articulated [ba] through a series of weakened sounds to [bɐ] or [bə] and then to [b]. [bə] is [b] followed by a barely audible schwa [ə], and [b] is a minimal sound without which /ba/ will become mute.[2] The Phoenicians would probably regard this whole series of sounds as different realizations of the same “sound” /ba/, of which [ba] or [bɐ] was the norm.

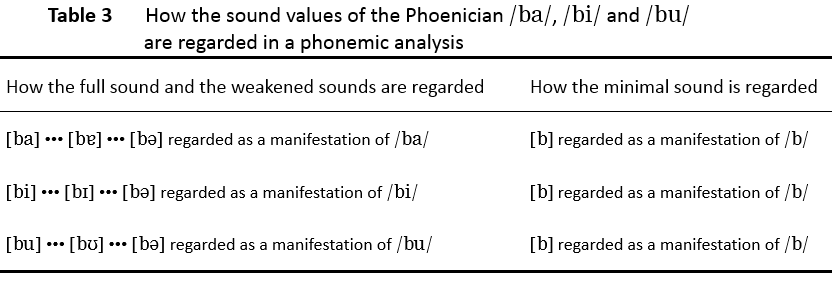

While the Phoenicians probably regarded [ba], [bɐ], [bə], and [b] as one “sound”, a conventional phonemic analysis may treat these sounds differently. [ba], [bɐ], and [bə] may be regarded as different realizations of the underlying syllable /ba/, whereas [b] may be seen as the phonetic realization of the phoneme or consonant /b/. It seems to make just as much sense for the Phoenicians to have regarded [bə] and [b] as one sound as it does for a linguist to regard [ba] and [bə] spoken in Phoenician as different realizations of /ba/. Indeed, to a Phoenician uninitiated in the segmental concept, the phonetic difference between [bə] and [b] might even be smaller than that between [ba] and [bə]. However, in a phonemic analysis, while [ba], [bɐ], and [bə] may be regarded as belonging to the same category, [bə] and [b] may be regarded as belonging to two different categories, as can be shown from Table 3 below.

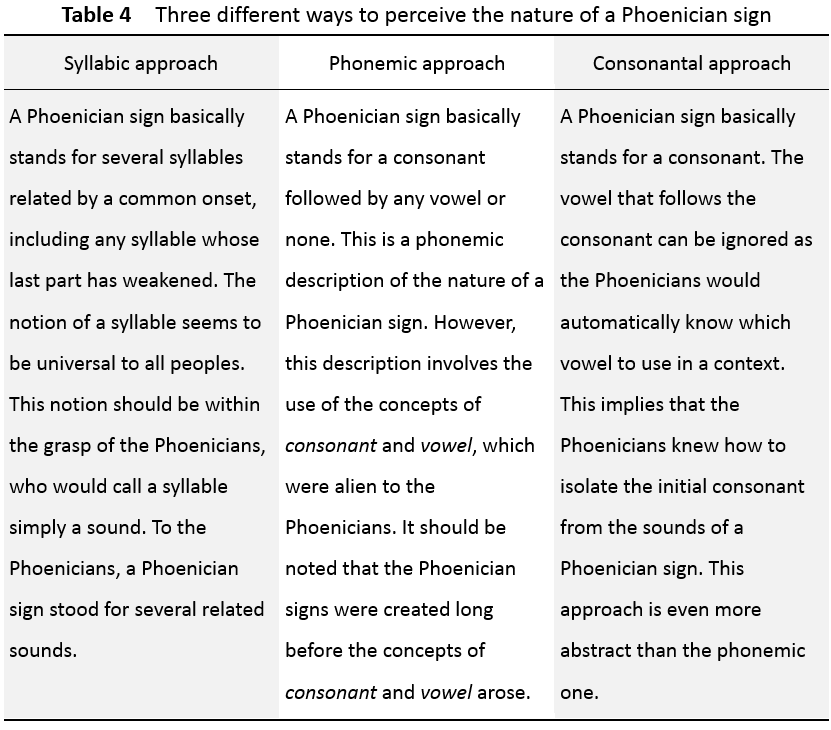

While it is universally agreed that a Phoenician sign is a phonogram, views are divided as to whether it is a syllabic sign or a consonantal one. The Phoenicians would probably regard a Phoenician sign as representing several “sounds”, which they felt were somehow semantically related. Take for example the Phoenician sign <_b>. To the Phoenicians, it represents /ba/, /bi/, /bu/, /ba:/, /bi:/, /bu:/, /be:/, or /bo:/. When it represents a syllable with a short vowel /ba/, /bi/, or /bu/, it might be read respectively as [bɐ], [bɪ], and [bʊ], or generally as a further weakened [bə] or [b]. There is no doubt that [bə] could still be regarded as a syllable. As for [b], it is a weakened form of [ba], [bi], or [bu], and so one could argue that the inner or underlying structure of [b] is the same as that of [ba], [bi], or [bu]. As the underlying structure of [ba], [bi], or [bu] is undoubtedly a syllable, one could argue that [b] is structurally or underlyingly a syllable, too. If this argument holds, the formula cα which we use for analysing the sounds of the Semitic languages is structurally or underlyingly a set of CV syllables, some of which can become so weakened that their rhyme (or V) may be elided. Since a Phoenician sign stands for cα, we believe that it is in essence a syllabic sign.

Many scholars hold that a Phoenician sign stands for the consonantal element of a CV syllable. The vocalic element of the syllable can be ignored as the Phoenicians would know which vowel to use, if any. This view implies that the Phoenicians knew how to isolate the consonant from the syllable. We deem it very unlikely for the Phoenicians to have known how to do that as the concept of consonant did not arise until the Greek segmental writing system had come into being. The Phoenicians did not need to have the concepts of consonant and vowel before they could use their script to read and write. To the Phoenicians, a Phoenician sign had several sounds. The proper reading of the sign in a written word would pose little difficulty for them once they recognised which word it was from the context. When they were unsure about which word was used, they could try out the likely sound combinations of the signs. A few attempts would probably enable them to know the lexical core meaning and then which word it was.

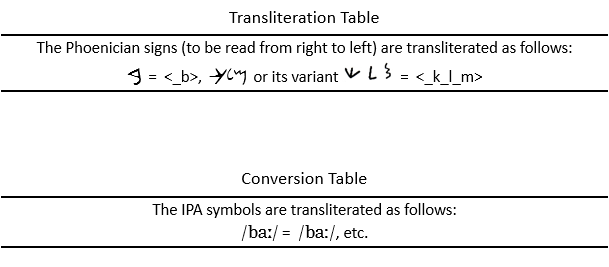

There are twenty-two signs in the Phoenician orthography, with which the Phoenicians wrote their language. For example, the Phoenician word for ‘king’ is written as <_k_l_m>, to be read from the right, as explained in §2. <_m> stands for /m_/, <_l> for /l_/, and <_k> for /k_/. (Here the phonetic symbol within the slashes represents the syllable onset, while the underscore represents the variable rhyme. In the basic structure of a Phoenician cα, the onset is an unvarying consonant while the rhyme is a variable vowel that can be elided at times.) Whichever is the sound value of /m_/ in <_k_l_m>, it is still written as <_m>. The same goes for /l_/ and for /k_/. The word /m_ l_ k_/, depending on its number, gender, and case, can be read in a great number of ways. No matter how it is read, the word is still written as <_k_l_m>. When used in isolation, <_k_l_m> can be read in different ways. Once a Phoenician understood its meaning from its context, he would naturally know how to read it, being a native speaker of Phoenician. It should be noted that some Phoenician signs may have variant forms. For example, /m_ l_ k_/ might also be written as a slightly different form of <_k_l_m>, as attested in the inscription on Aḥiram’s sarcophagus dated to around 1000 BC. The Phoenicians wrote their language essentially syllable by syllable, not consonant by consonant.

To sum up, there are basically three ways to perceive the nature of a Phoenician sign. The table below is a critical summary of these three approaches:

[1] Examples of CVCV turning into CVC can also be found in English. The first two syllables of the words medicine and reference may be spoken as /med-/ and /ref-/ respectively, apart from /medɪ-/ and /refə-/.

[2] A minimal sound such as [b] and [p] may not be very audible in isolation, but its presence will be made more salient by a preceding vowel. For example, in the Arabic word /kutub/ ‘books’, the [b] sound at the end of the word is brought out by the preceding [u].

26 December 2016

Views: 674