Preface to The Origin of the Greek Alphabet

The birth of the Greek alphabet in the first quarter of the first millennium BC marks a milestone in the development of the writing systems of mankind. A new type of writing system suited to the phonological structures of Greek and many other European languages had been invented by the Greeks at the latest by the eighth century BC. However, nobody has yet been able to give a satisfactory account of the full history of the birth of the Greek alphabet. The essence of the process by which this new writing system came into being is generally described as follows: The Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet to write their language. As the Phoenician writing system is consonantal, its signs denote only consonants. When some of the consonantal Phoenician signs changed into vowel letters, a new type of writing system was born. Some letters of the Greek alphabet denoted vowels, and the others consonants.

Back in 2008 we embarked on a comparative study of the world’s major writing systems. When writing about the ancient scripts, we gradually came to realize that in the study of ancient scripts it is important to try to see them from the ancients’ perspective in order to understand how the scripts actually work. With this in mind, we tried to study the Phoenician signs from the Phoenicians’ perspective and came to realize that to regard the Phoenician writing system as consonantal has in effect prevented one from getting a true picture of the history of the birth of the Greek alphabet, because the Phoenician script does not operate on a consonantal basis. The Phoenicians’ view of the nature of their script is actually quite different from the mainstream one held by most linguists today.

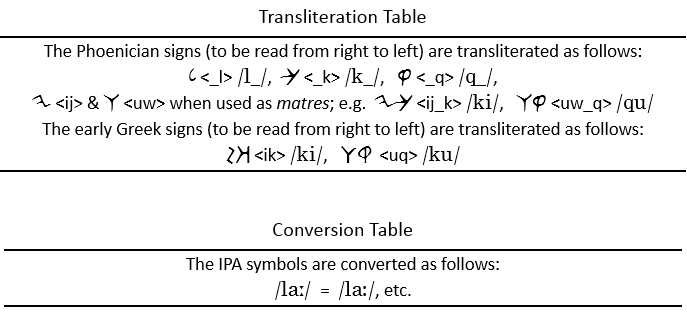

Linguists are generally agreed that a Phoenician sign stands for a consonant followed by any vowel or none. For example, the Phoenician sign <_l> stands for the consonant /l/ followed by any vowel or none. As the Phoenician vowel system is generally assumed to comprise the following vowels: /a, i, u, a:, i:, u:, e:, o:/, the Phoenician sign <_l> presumably stands for /la, li, lu, la:, li:, lu:, le:, lo:/ or simply /l/. This is the phonemic view of the nature of a Phoenician sign. [Authors’ remarks: For technical reasons, many special symbols, such as Phoenician signs and IPA symbols, cannot be displayed here, and so have to be transliterated or converted into ordinary symbols. For these special symbols, please refer to the relevant transliteration or conversion table at the end of this preface. The special symbols in the main text will be treated likewise. Please also note that Phoenician writing runs from right to left. Thus the above-mentioned Phoenician sign is transliterated as <_l>, not <l_>. We contend in this treatise that one must try to see Phoenician writing from the Phoenicians’ perspective.]

The mainstream view of the nature of a Phoenician sign even goes one step further than the phonemic one. It focuses on the unvarying initial consonant that a Phoenician sign represents while ignoring the variable vowel, if any, that follows the consonant. Linguists holding this view assert that Phoenician signs denote only consonants. For example, the Phoenician sign <_l> denotes only the consonant /l/.

It is understandable that Western linguists describe the sound of a sign in a foreign script in terms that are most familiar to them—terms like consonants and vowels. However, it must be noted that these terms and the concepts they express are alien to ancient peoples, including Phoenicians. The Phoenicians most likely regarded the Phoenician signs in a more primitive way. To them, a Phoenician sign had several sounds, and it was the context of a piece of writing that would tell them which sound it was, just as the context of the following sentence would tell the English readers how the word read should be read: The book I’ve just read is easy to read. While words with the same spelling but different pronunciations are fairly rare in English writing, it is a very common phenomenon in the Phoenician script for a Phoenician sign to be read differently to convey different grammatical meanings, such as case and number. On seeing for example the Phoenician sign <_l>, the Phoenicians would recognize this fairly pictorial sign as a sign for a shepherd’s goad, whose Phoenician name is akin to Hebrew lāmed ‘goad’. The initial part of the sign name lā would trigger off in their mind all the sounds that the sign <_l> could represent, namely /la, li, lu, la:, li:, lu:, le:, lo:/ and /l/. To write any of these sounds, the Phoenicians would use the same sign <_l>. They would take each of these sounds as a single whole. Most likely, they were not even aware that each sound could be split into smaller parts.

The Phoenicians, however, might run into situations in which even the context of a piece of writing failed to determine the sound of a Phoenician sign, such as the correct reading of an unfamiliar foreign name. They would then be obliged to use a so-called mater lectionis ‘mother of reading’ after a Phoenician sign to help indicate which sound it was. How does a mater tell the readers how the preceding Phoenician sign should be read?

Strangely enough, the modus operandi of a mater in Semitic alphabetic writing does not seem to be very well understood today. It is often said that a mater is a vowel indicator. Sometimes a mater is even regarded as a vowel letter. However, how a mater actually functions remains unexplained.

From the study of ancient Egyptian writing, we came to know that the matres lectionis used in Semitic alphabetic writing most probably originated from this ancient script, and by working out how the matres were born in Egyptian writing, we came to know how they were used to help indicate the sound of a foreign name. We believe that if one knows how the matres came into being in Egyptian writing, one will know how they actually function as sound indicators, and that, with a good understanding of their function as sound indicators, one can give a satisfactory account of the birth of the Greek alphabet. To find out how the matres came into being and how they functioned in Egyptian writing, the readers can refer to §8 of the main text.

It is possible that the first Semitic alphabet was invented by the scribes of the Hyksos dynasty, which ruled the Nile Delta from the Egyptian city Avaris for more than 100 years from about 1650 BC. Avaris had a large population of Semitic immigrants, and the Hyksos rulers were probably Western Semites. As Western Semites had no writing of their own, the Hyksos scribes wrote in ancient Egyptian. Some scribes might have used their knowledge of Egyptian writing to invent the first Semitic alphabet, from which the Phoenician script is descended via proto-Canaanite writing. The knowledge of the first Semitic alphabet, including how matres are used to write foreign names, would then be passed on down the generations from users to learners among the Western Semites.

The Phoenicians are well-known seafaring traders. When doing business with other Mediterranean peoples, Greeks included, the Phoenicians probably needed to record some Greek names, such as the names of their trading partners and the ports of call, with the aid of matres. The Phoenicians might have attempted to record Greek names as early as the twelfth century BC. We believe that these attempts mark the beginning of Greek alphabetic writing.

Sooner or later it would come to the notice of the Greeks that not only could the Phoenicians write out their names with merely about twenty Phoenician signs but they could also read out the names easily, sometimes with remarkable accuracy. This might have motivated some Greeks to learn the Phoenician alphabet. There is evidence in the various regional scripts of ancient Greece to suggest that the Greeks learned the Phoenician alphabet by noting how the Phoenicians wrote a Greek name. We believe that the Phoenician way of writing Greek names would be determined by both the Phoenicians’ perception of Greek sounds and their method of writing foreign names. The way the Phoenicians wrote out the sounds of Greek names would set the model from which the Greeks developed their own writing.

This treatise argues that if proto-Greek alphabetic writing developed from the above model, it would evolve quite naturally into the different regional scripts of ancient Greece in the second quarter of the first millennium BC. If it is true that proto-Greek alphabetic writing began when the Phoenicians tried to record Greek names, then the better one can understand how the Phoenicians perceived Greek sounds and how they wrote foreign names, the better one can reconstruct proto-Greek alphabetic writing. When reconstructing proto-Greek alphabetic writing, one should of course also take into account the various regional scripts of ancient Greece, because one needs to explain how the former could plausibly evolve into the latter.

How the Phoenicians would write the Greek sounds /ki/ and /ku/ in proto-Greek alphabetic writing can be used as an example to illustrate the above point. Judging from the regional scripts of ancient Greece, we believe that it is possible that under the influence of their mother tongue the Phoenicians would hear the Greek sounds /ki/ and /ku/ as the Phoenician sounds /ki/ and /qu/ respectively, because they would probably identify the Greek sounds /ki/ and /ku/ with the Phoenician sounds /ki/ and /qu/. To write the sounds /ki/ and /qu/ in a foreign name, the Phoenicians would use the forms <ij_k> and <uw_q>, which should be read from right to left in accordance with the direction of writing in Phoenician. The second signs <ij> and <uw> are matres used to help indicate the sounds of the first signs <_k> and <_q>. When the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, they simply followed the Phoenicians’ lead in writing the Greek sounds /ki/ and /ku/ as <ij_k> and <uw_q>. This, we believe, could be the reason why the Greek sounds /ki/ and /ku/ were written as <ik> and <uq> in the regional scripts of ancient Greece. For the Phoenician way of writing the other Greek sounds and for a fuller history of the birth of the Greek alphabet, see the main text.

To better understand how the Phoenician writing actually works, we learned from an Egyptian the writing system of modern Arabic, which is descended from Phoenician through Aramaic. To find out how the Phoenicians might perceive some Greek sounds, we requested our Egyptian teacher to transcribe in Arabic letters some Cantonese syllables beginning with /s/, /h/, and /th/. The findings are revealing, for they provide surprisingly simple answers to some much-debated questions about the origin of some written forms used in the regional scripts of ancient Greece.

Even though the Phoenician way of writing Greek names is not attested, this does not mean that there was no need for the Phoenicians to write Greek names. The proto-Canaanite and the Phoenician inscriptions belonging to the period from the twelfth to the eighth century BC are so few and they are used for such limited purposes that small wonder there is no inscriptional evidence for the Phoenician way of writing Greek names. This treatise argues that the Phoenicians needed to record Greek names with the aid of matres in their commercial contacts with the Greeks. We believe that one can still figure out how they would record Greek names by studying how foreign names are written in ancient Egyptian and in Semitic alphabetic scripts such as modern Arabic or Hebrew. To this end, we studied how foreign names are written in ancient Egyptian and in modern Arabic.

This treatise offers a whole new perspective on the history of the birth of the Greek alphabet. In the treatise, the current views on this issue and ours are compared. The treatise should be of great interest to linguists and phoneticians, especially those taking an interest in the world’s writing systems. General readers who are curious about the genesis of the Greek alphabet are also likely to find the subject of the treatise interesting.

25 December 2016

Views: 834