8 Writing foreign names in ancient Egyptian

An Egyptian name usually comprises a number of ordinary words. Writing an Egyptian name is no different from writing ordinary words, and so it also involves the use of logograms, phonograms, and determinatives. However, writing a foreign name is a different matter. The Egyptians would come to realize that the most direct and the easiest way of writing a foreign name was to use monoconsonantal phonograms to write its sound syllable by syllable, without bothering much about its sense. However, the problem was that they might not know how to read such a name afterwards, because even a monoconsonantal phonogram had multiple sound values. They had to find a way to specify the sound value of a monoconsonantal phonogram when writing a foreign name. This is where the so-called matres lectionis ‘mothers of reading’ came into play.

8.1 The birth of matres lectionis in ancient Egyptian writing

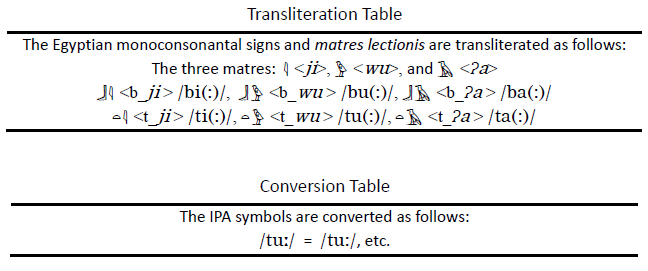

As their writing evolved, the Egyptians eventually discovered an ingenious way of writing the sounds of foreign names. As early as around 2150 BC, they came to know the use of three monoconsonantal signs <j_>, <w_>, and <Ɂ_> to aid the reading of foreign names (Loprieno 1995:14). Linguists call these signs matres lectionis. The Egyptians discovered that the phonograms <j_>, <w_>, and <Ɂ_> would lose their sound most easily when the following two conditions were met: (1) they were read lightly as /ji/, /wu/, and /Ɂa/ respectively, and (2) they were preceded by a phonogram with the same rhyme.

Why would <j_>, <w_>, and <Ɂ_> lose their sound under these circumstances? Why would <j_>, for example, lose its sound easily when it was read lightly as /ji/ and when it was preceded by a phonogram read as [ci] (c stands for any initial consonant)? One can explain the sound loss of <j_> from an articulatory standpoint. When [ji] is pronounced light and fast after a syllable ending in [i], there is a tendency for the two syllables to coalesce into a single syllable ending in [i:]. The sound changes can be shown like this: [ci] + [ji] > [ciji] > [ciii] > [ci:]. Since the sequence of sounds [i] + [j] + [i] in [ciji] is made by one and the same articulatory posture, and since the duration of [j] is much shorter than that of [i], the onset [j] is readily assimilated to the preceding peak [i]. The second syllable [ji], therefore, seems to have disappeared in the resulting syllable [ci:]. Thus, <j_>, representing /ji/, would lose its sound ultimately when read lightly and when preceded by a rhyming phonogram. By the same token, <w_> would lose its sound easily when read lightly as /wu/ and when preceded by a rhyming phonogram. Since the relationship between [w] and [u] is similar to that between [j] and [i], the following sound changes would take place: [cu] + [wu] > [cuwu] > [cuuu] > [cu:]. The case of <Ɂ_> is only slightly different. <Ɂ_>, representing /ʔa/, would also lose its sound easily when preceded by a rhyming phonogram. The sound loss of <Ɂ_> can be explained in this way: [ca] + [Ɂa] > [caɁa] > [caa] > [ca:]. The glottal stop [Ɂ] tends to disappear when located between two [a] sounds because [aa] requires less effort to say than [aɁa].

<j_>, <w_>, and <Ɂ_> ultimately lost their sound in certain words under the circumstances described above. These three phonograms, despite their loss of sound, seemed to assume a new function of indicating the proper reading of the preceding phonogram. Take for example the Egyptian syllable /bi:/ that was written as <b_j_>. This syllable was originally read as /biji/ before <j_> lost its sound. The presence of the silent <j_> thus seemed to indicate that <b_> was to be read as /bi/, but not /ba/ or /bu/. By the same token, a silent <w_> in <b_w_> would indicate that <b_> was to be read as /bu/, but not /ba/ or /bi/. A silent <Ɂ_> in <b_Ɂ_> would indicate that <b_> was to be read as /ba/, but not /bi/ or /bu/. Over time, the Egyptians came to realize that <j_>, <w_>, and <Ɂ_> could be used as auxiliary signs to indicate the proper reading of the preceding phonogram.

8.2 The creation of matres was need-driven

In a sense, a mater is like a determinative in ancient Egyptian writing. The creation of both the matres and the determinatives was probably driven by need. Since a monoconsonantal phonogram has three basic sound values, there is a need at times to use a mater to determine which of the three sound values is the intended one, as in the case of the writing of an unfamiliar foreign name. Just as a determinative is employed to disambiguate a written word with multiple semantic values, so a mater is used to disambiguate a phonogram with multiple sound values. A mater can thus be regarded as a sort of “phonetic determinative”. To sum up, a mater and a determinative can be regarded as a sort of ancillary pointer, attached to the main body of a written word, thus enabling the reader to grasp the sound or meaning of the word more quickly. Many see a mater as a vowel letter (Healey 1994:74). This is not correct because a mater always represents a CV syllable in Egyptian writing, not a single vowel sound. A mater is not even a vowel indicator, as suggested by some linguists (Gelb 1952:169; Naveh 1987:9). Strictly speaking, a mater is a syllable indicator used to indicate the preceding phonogram’s right syllable that rhymes with the mater.

8.3 The rhyming principle of matres

In many pre-literate societies rhymes were used as a powerful mnemonic device to help pass myths and legends orally from generation to generation. In ancient Egypt, however, rhymes were utilized for a new purpose, the significance of which is much greater than is generally realized. There, matres were used as rhymes to determine the sound values of phonograms in writing. Since ancient Egyptian has only three basic vowels or rhymes, the rhyming principle is very easy to use in ancient Egyptian writing.

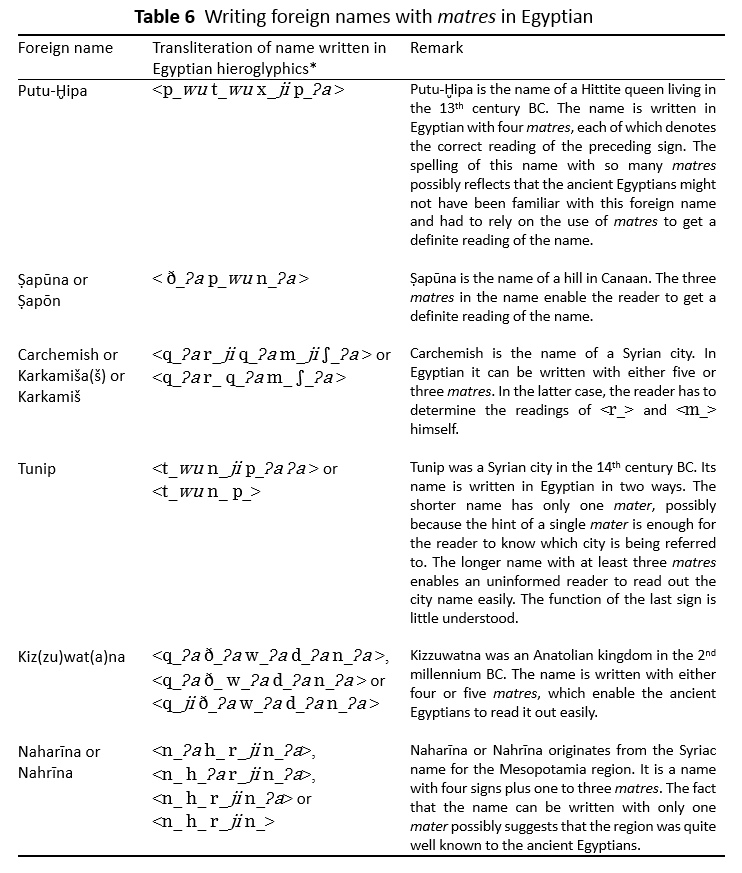

The Egyptians would have little difficulty in reading matres in foreign names as matres were fairly easy to identify in Egyptian writing. When a reader encounters a foreign name in a piece of Egyptian writing, the context will point to its nature as such. Besides, the signs with which to write a foreign name always appear in a particular pattern in which each phonogram is generally followed by a mater. Since there are only three matres, their recurrence in a written word also makes it easy for a reader to recognize it as a foreign name. According to Gelb, there were intensive contacts in the second millennium BC between the Egyptian kingdom and the neighbouring lands. As there was a regular need to write foreign names in Egyptian, the convention to write these names systematically with matres was eventually established in ancient Egypt. To illustrate how the ancient Egyptians wrote foreign names with matres, Gelb cited the following examples (1952:168-169):

*A specific example can be used to illustrate how a foreign name written in Egyptian hieroglyphics is transliterated in this treatise. To write the sound /tu(:)/ in a foreign name, the Egyptian scribes would use the so-called monoconsonantal sign <t_> plus the mater <w_>. <t_> represents /t_/; <w_>, a silent mater read as /wu/, requires the preceding sign <t_> to rhyme with it. Thus <t_> is to be read as /tu(:)/. <t_w_> are here transliterated into IPA symbols within angle brackets as <t_wu>. In the transliteration here the mater is written in italics. If <t_> is not followed by a mater, its reading is to be determined by the reader.

When reading the signs <t_wu> in a foreign name, the Egyptian scribes would read them automatically as /tu(:)/ as they were familiar with the use of matres. However, the Egyptian scribes would have to decide whether <t_wu> should be read as /tu/ or as /tu:/. It must be stressed here that they would by no means see <t_> as representing a consonant sound and <wu> as representing a vowel sound. It should also be noted that when writing <t_wu> on papyrus, the Egyptian scribes would most probably use a cursive form called hieratic.

27 December 2016

Views: 352