9 The first Semitic alphabetic script and some of its descendants

It is said at the outset of this treatise that nobody knows for certain why, how, when, and where exactly Greek alphabetic writing began. The same can also be said about the origin of Semitic alphabetic writing. The Proto-Sinaitic and the early Proto-Canaanite inscriptions are the earliest extant Semitic alphabetic writings, which may be dated to about 1700‒1500 BC. These inscriptions attest to the Western Semites’ first attempts to use the alphabetic signs to write their language. How did such signs come into being?

From a papyrus now in the Brooklyn Museum in New York, one can see how Semitic names were written by the ancient Egyptians. The papyrus, whose place of origin is probably Thebes in Egypt, contains a record of claims of ownership in a civil lawsuit between a noblewoman and her father. The record was written probably during the second half of the eighteenth century BC. It contains a long list of servants’ names, at least 45 of which are identified as those of Asiatic people. These people, we believe, are most likely Semites coming from lands adjacent to the eastern part of Egypt. The name list points to both the possible presence of a sizable population of Semitic people in Thebes and the Egyptians’ need to record their names in Egyptian hieroglyphs for various purposes. Such a need most likely arose earlier than 1700 BC, and the simplest way for the Egyptians to write Semitic names was probably to write their sounds by means of the Egyptian monoconsonantal signs.

9.1 The possible origin of the first Semitic alphabet

In regard to the writing of Semitic names by means of Egyptian monoconsonantal signs, one should perhaps mention the city of Avaris, which was situated at the eastern fringe of the Nile Delta and was connected to Sinai and Canaan by overland routes. It was established as early as the twentieth century BC by King Amenemhat I, who ruled Egypt from about 1985 to 1956 BC. It was called Hutwaret in Egyptian, which, when rendered in Greek, became Avaris. Because of its location Avaris was a popular destination for Semitic immigrants from nearby Canaan and other parts of Western Asia. By 1700 BC there was most likely a large population of Semitic immigrants in Avaris. In about 1650 BC the Hyksos dynasty set up court there. Hyksos means ‘rulers of foreign lands’. Judging from the names of the six kings of the Hyksos dynasty, these foreign rulers were most probably Western Semites. They ruled the Nile Delta from Avaris for more than 100 years.[1]

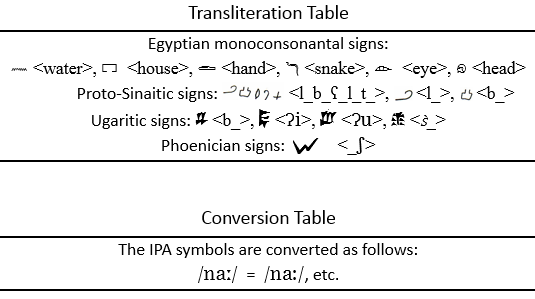

Before the creation of the Semitic alphabet, the Western Semites did not know how to write their native language. The century-long Hyksos dynasty possibly provided conditions favourable for the creation of a Semitic alphabet. The few inscriptions left behind by the Hyksos reveal that the scribes wrote in Egyptian. If these scribes were descendants of the Semitic immigrants, as some of them most probably were, they were likely to be bilingual in Egyptian and West Semitic. Such scribes were in a good position to make an attempt to write their native language in hieroglyphs. As it is possible that the royal court and a large portion of the population in Avaris spoke West Semitic, these scribes might even have been assigned the task of finding a good way to write West Semitic. They must have known how the Egyptians wrote the Semitic names, and this way of writing Semitic names might have inspired them to create their own script. When reading a Semitic name written in hieroglyphs that contained, say, the monoconsonantal sign <water>, they would know that it represented the Semitic syllable /na/, /ni/, /nu/, /na:/, /ni:/, /nu:/, /ne:/, or /no:/ (assuming that West Semitic had these eight vowels at that time). In theory, they could use <water> to stand for these sound values too. However, as the sign <water> was pictorial, its meaning ‘water’ did not relate well to the above Semitic syllables. As the sign <water> was probably called mēm or the like in West Semitic, they would probably prefer to use the water sign <water> to stand for /ma/, /mi/, /mu/, /ma:/, /mi:/, /mu:/, /me:/, or /mo:/. The first CV syllable of mēm was /me:/. It was one of the syllables that the sign <water> could stand for, and it was a sound that could easily be associated with the object water designated by the sign. The use of the sign <water> to represent /m_/ would be more intimate to the Western Semites as it represented the first sound of the word water in their native language. They were thus inclined to use the sign <water> to represent /m_/ rather than /n_/.

The CV syllable /me:/ can be regarded as the acrophone of mēm, which is the Semitic name of the Egyptian sign <water>. It should be stressed here that the acrophone of mēm is a CV syllable, not a consonant as held by many linguists. The acrophone of a Semitic noun is relatively constant and so can be associated more easily with the meaning of the noun than the succeeding sound of the noun. Take the Ugaritic noun for ‘dog’ as an example. It can be pronounced as /kalbu/, /kalbi/, /kalba/, /kalbatu/, /kalbati/, /kalbata/, etc. Its pronunciation varies with its number, gender, and case. No matter how it is inflected, its acrophone remains unchanged. It is always /ka/. Just as the sound /ka/ is easily associated with the meaning ‘dog’ in Ugaritc, so the sound /me:/ is easily associated by the Western Semites with the meaning ‘water’ and thus with the water sign <water>. When the <water> sign represents /me:/, it is to a certain extent a motivated sign to the Semites, and this facilitates the learning of the Semitic alphabet. Once the Hyksos Semitic-speaking scribes had grasped the above acrophonic principle, they would be in a good position to create the necessary signs for representing all the syllables of their native language.

When adopting such Egyptian hieroglyphs as <house>, <hand>, <cobra>, <eye>, and <head> for use as Semitic alphabetic signs, the Hyksos scribes could just call these hieroglyphs by their Semitic name and then convert the signs that represented the acrophones of the designated nouns into signs with multiple sound values. After finding all the necessary signs, which should number less than thirty, they would probably try to arrange them in a certain order to form perhaps a kind of alphabet rhyme so as to facilitate learning. The first Semitic alphabet could have been formed in this way, and the Hyksos scribes in the Nile Delta area must have followed the Egyptian tradition of writing on papyrus. Given the climatic conditions in the Delta area, it is not surprising that the perishable papyri on which they wrote their native language can hardly be found today.

9.2 The Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite alphabets

The creation of the first Semitic alphabet may not be as easy as it appears, but once created, it is not very difficult to learn. Given the chance and the motivation, even ordinary Semites can learn it within a short period of time. After the creation of the first Semitic alphabet, some Semites might have found it convenient to have a rudimentary knowledge of writing to meet some elementary needs in daily life, such as writing their own name, their gods’ names, or some short wishes.

The idea that it was possible to use less than thirty pictographic signs to write Semitic words must have spread during the second quarter of the second millennium BC from Egypt eastwards to Sinai and Canaan. There are, however, only about thirty Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions and about twenty-five Proto-Canaanite inscriptions that can attest to the existence of the first Semitic alphabet that spread to Sinai and Canaan (Sass 1988:157). Moreover, the dates of the Proto-Sinaitic and early Proto-Canaanite inscriptions are uncertain. If it is true that the first Semitic alphabet was created during the Hyksos dynasty, then this alphabet could have spread to Sinai and Canaan in the seventeenth or sixteenth century BC. The Semitic alphabet that reached Sinai is called the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet, and the Semitic alphabet that reached Canaan is called the Proto-Canaanite alphabet.

From an inscription of a few linear signs <l_b_ʕ_l_t_> scratched on a stone sphinx in a temple in the Sinai Peninsula, one can see how the Western Semites put their writing to use. The inscription, dated to the second quarter of the second millennium BC, comprises five Proto-Sinaitic signs <l_b_ʕ_l_t_>, read by the English Egyptologist Alan H. Gardiner as lb‘lt ‘to (the goddess) Ba‘alat’. We believe that these signs stand respectively for /l_/, /b_/, /ʕ_/, /l_/, and /t_/. The linear signs are still fairly pictorial. The first sign <l_> looks like an ox-goad. Regardless of what it is called in the Egyptian language, the Western Semites called it by its Semitic name, which is akin to Hebrew lāmed. The sign, however, does not represent lāmed ‘ox-goad’. It is a syllabic sign with multiple sound values. Not only can it represent the acrophone /la:/ of the noun lāmed, but it can also represent all the possible sounds with the same onset, namely /l_/. Here it stands for the Semitic word for ‘to’, which is pronounced as /l/ plus a definite vowel. The other Sinaitic signs are constructed most probably in the same way as <l_>. For example, the second sign <b_> was probably derived from the Egyptian <house> sign, which depicts the floor plan of a house. In Egyptian, the <house> sign, meaning ‘house’, was read as /p_r_/. The Western Semites adopted this sign and called it bēth or the like, which means ‘house’ in Semitic. The sign <b_> represents /b_/.

The Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions are quite homogeneous. The signs are fairly pictographic. The stance of the signs is not fixed, and neither is the direction of writing. The signs can run vertically or horizontally. They can also run from right to left or from left to right. The Proto-Canaanite inscriptions are less homogeneous. The early signs are quite pictographic, while the later ones are more linear. It should be noted that the dates of the Proto-Canaanite inscriptions found in Canaan and Phoenicia range from the seventeenth century to the early eleventh century BC.

9.3 The Ugaritic alphabet and its significance

The first Semitic alphabet probably spread from Egypt in the seventeenth or sixteenth century BC eastwards to Sinai and Canaan, and then northwards to the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, including the region called Phoenicia by the ancient Greeks. By the thirteenth century BC the Proto-Canaanite alphabet had reached, probably via Phoenicia, Ugarit, an ancient seaport to the north of the Phoenician coastal cities Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos. The use of a Semitic alphabetic writing system at Ugarit in the thirteenth and the early twelfth centuries is well attested by nearly two thousand clay tablets that have been unearthed from there since 1929.

Ugarit in the Late Bronze Age was a cosmopolitan city, where cuneiform was used to write such languages as Akkadian, Hurrian, and Hittite. Akkadian cuneiform was the lingua franca of the time used for international diplomacy and commerce in such areas as Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Canaan, and Egypt. The scribe or scribes who created the Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform script must have been familiar with both the Akkadian cuneiform writing and the linear Semitic alphabetic writing that had spread to Ugarit. The Ugaritic scribes must have perceived the big advantage of the Semitic alphabetic script: it used far fewer signs than the Akkadian script. We believe that the scribes, inspired by the Semitic alphabetic writing, started to create their own script for writing Ugaritic, a Semitic language akin to Phoenician and Hebrew, while maintaining the Mesopotamian scribal tradition of writing cuneiform from left to right on clay tablets.

A clay tablet (KTU 1.6) inscribed in alphabetic Ugaritic contains a statement to the effect that the scribe Ilimilku was working under the patronage of King Niqmaddu. According to Bordreuil and Pardee, two experts on Ugaritic writing, the said King Niqmaddu should be Niqmaddu III (who died during the last decade of the thirteenth century BC), rather than Niqmaddu II (who died about 1350 BC) as was commonly believed. Their reason is that no tablets have been found with the names of the two kings Arḫalbu and Niqmepa (who reigned after Niqmaddu II) written in alphabetic Ugaritic. If the said King Niqmaddu had been Niqmaddu II, then, in all likelihood, the names of Arḫalbu and Niqmepa should have appeared on tablets inscribed in alphabetic Ugaritic. However, their names are not attested in alphabetic Ugaritic. This is probably because the Ugaritic alphabet had not yet been invented during their reign. This indirectly supports the hypothesis that the said King Niqmaddu should be Niqmaddu III (Bordreuil & Pardee 2009:19-20).

The above-mentioned clay tablet (KTU 1.6) thus attests to the fact that the Ugaritic alphabetic script was in use in the second half of the thirteenth century BC. The Ugaritic alphabet must have been invented at an earlier date. According to Bordreuil and Pardee, this alphabet had already been invented during the reign of Ammistamru II (ca. 1260‒1235 BC), since his name is attested in Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform whereas the names of Arḫalbu and Niqmepa (who reigned before Ammistamru II) are not. Thus they believe that the Ugaritic alphabet was not invented until sometime in the first half of the thirteenth century BC (2009:20). If their hypothesis is correct, then the Proto-Canaanite alphabet might have reached Ugarit in the fourteenth century BC. The Ugaritic scribes would need some time to familiarize themselves with the linear Proto-Canaanite alphabet before they could invent their own alphabet in cuneiform.

The Ugaritic alphabet is basically of the same nature as the West Semitic alphabets, such as Phoenician, Hebrew, and Aramaic, in which one sign represents several CV syllables with a common onset. It is unthinkable that this kind of alphabet could have been invented independently at Ugarit without an existing Semitic alphabet to base on.[2] Thus the prior existence of a Semitic alphabet is a prerequisite for the invention of the Ugaritic alphabet, and this Semitic alphabet should have been the Proto-Canaanite alphabet that had probably reached Ugarit in the fourteenth century BC.

The Ugaritic alphabet is well attested by more than a dozen abecedaries, the first of which was found in 1939 (Bordreuil & Pardee 2009:7). Abecedaries are lists of signs arranged in a standard order. The order of the signs in the Ugaritic alphabet is basically the same as in Modern Hebrew. It can be inferred from this that the above two alphabets should have derived from a common source, which is most likely the Proto-Canaanite alphabet. The Ugaritic alphabet originally has 27 signs, and the modern Hebrew alphabet has 22 signs. Despite the difference in the number of signs, the order of the signs in these two alphabets is essentially the same. It can be inferred from the original 27 signs in the Ugaritic alphabet that the Proto-Canaanite alphabet should have at least 27 signs. The 27 Ugaritic signs should be arranged essentially in the same order as in the Proto-Canaanite alphabet. There should also be abecedaries with 27 signs or more for the learning of the Proto-Canaanite alphabet, but their existence is not attested probably because they were written on papyrus or some other perishable material.

The task of inventing the Ugaritic alphabet would be made much easier for the Ugaritic scribes if they had for reference an abecedary of the Proto-Canaanite alphabet, which we believe they most probably had. They might have thought of borrowing the appropriate Akkadian syllabograms directly and then transforming them into signs with multiple sound values, but might have been deterred by the number of strokes or wedges required to write such syllabograms, which were a far cry from the simple signs in the Proto-Canaanite alphabet. The Proto-Canaanite signs written in the first half of the thirteenth century BC are barely attested by the extant Proto-Canaanite inscriptions, and so one can only guess that they should look slightly more pictorial than the better-attested twelfth-century Proto-Canaanite signs. The Ugaritic scribes probably had great difficulty in turning the still pictographic Proto-Canaanite signs into cuneiform ones. As they were very much used to writing unmotivated cuneiform signs, it is probable that they decided to design their own signs from scratch after much consideration. The form of each sign in the new script that they produced was simple yet distinct, and had on average much fewer strokes or wedges than the Akkadian syllabograms. With the invention of the new signs, the scribes could now use a small number of signs to write Ugaritic (see Appendix 2).

The early Proto-Canaanite signs can be said to be motivated because the name of a sign generally refers to the object depicted by the sign. How did the Ugaritic scribes call the signs in their alphabet, which apparently are not pictorial? They could have called the new signs by the Proto-Canaanite names. However, as the Ugaritic signs are not pictorial from the start, the scribes might have found it rather unnatural to call them by their traditional names. They might have called the signs simply by the first CV syllables of these names. A broken Ugaritic abecedary tablet (KTU 5.14) shows a list of twenty signs, each of which is annotated by an Akkadian syllabogram. This syllabogram might indicate either the name or a sound value of the annotated sign. For example, the second sign <b_> in the Ugaritic alphabet might be called bēth or the like as part of the tradition. Or it might be called bē, as annotated by the Akkadian syllabogram with the sound value of /be/.

There are three signs appended to the original alphabet with 27 signs: <Ɂi>, <Ɂu>, and <ś_>, numbered as signs 28, 29, and 30 respectively. Sign 30 is used, some scholars believe, to represent a Hurrian sound which is transliterated here as ś. Sign 28 stands for /Ɂi/, /Ɂi:/, and /Ɂe:/, whereas sign 29 stands for /Ɂu/, /Ɂu:/, and /Ɂo:/. Before the addition of these two signs, sign 1 <Ɂa> originally stands for /Ɂ_/, i.e., it stands for /Ɂ/ plus any vowel or none. After the addition of signs 28 and 29, sign 1 now only stands for /Ɂa/ and /Ɂa:/. However, a problem arose when signs 28 and 29 were added: How should the sound /Ɂ_/ be represented in a word when the vowel after /Ɂ/ has become /ə/ or is elided? If the scribes knew the sound of the original vowel before it weakened into /ə/ or was elided, then they would know which of the three signs (signs 1, 28 and 29) should be used. But if they did not know the sound of the original vowel, they would have to decide arbitrarily which of the three signs was to be used by consensus. If signs 28 and 29 had not been added, such a problem would not have arisen. The addition of signs 28 and 29 to the Ugaritic writing system has in effect both advantages and disadvantages.

The ways in which the Ugaritic alphabet was used at Ugarit during the thirteenth century BC provide an invaluable insight into the ways in which the Proto-Canaanite alphabet could have been used in nearby Phoenicia during the same period. From the clay tablets unearthed from Ugarit, one knows that alphabetic cuneiform was used for writing the native language at Ugarit for administrative, economic, epistolary, religious, literary, and scholastic purposes while Akkadian was used as a lingua franca for legal and diplomatic purposes. One can imagine that the Proto-Canaanite script and Akkadian were probably used in more or less the same ways in Phoenicia during the same period.

9.4 The Phoenician alphabet

It can be inferred from the invention of the Ugaritic alphabet in the first half of the thirteenth century BC that a Semitic alphabet consisting of at least 27 signs must have been in use at least for some time at Ugarit before the invention of the Ugaritic alphabet. The probable candidate for this Semitic alphabet was most likely the Proto-Canaanite alphabet that had spread to Ugarit via Phoenicia. Thus it is likely that this Proto-Canaanite alphabet was in use in the second half of the fourteenth century BC in Phoenicia. Apart from the circumstantial evidence of the Ugaritic alphabet, there is no extant data, however, to support this point.

Judging from the wide use of the Ugaritic script at Ugarit in the thirteenth century BC, the Proto-Canaanite alphabet should have also been widely used for writing the Canaanite dialects spoken in Phoenicia in the same period. However, the extant inscriptions barely attest to the use of the Proto-Canaanite alphabet in that area then. There are in fact very few Proto-Canaanite inscriptions that can be dated to the thirteenth century BC. The earliest extant Proto-Canaanite abecedary attested by the ostracon from ʽIzbet Ṣarṭah in Canaan is dated to the twelfth century BC. This abecedary seems to attest a Semitic alphabet with only 22 signs, five signs less than the Ugaritic abecedary. The Canaanite inscriptions found in Phoenicia, dated as belonging to the period between the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC, also attest to the use of an alphabet with 22 signs. It seems that some signs in the Proto-Canaanite alphabet were not required to write the Canaanite dialects in ʽIzbet Ṣarṭah and in Phoenicia in the twelfth century BC.

The Phoenician alphabet has at least 5 signs less than the Proto-Canaanite alphabet that gave rise to the invention of the Ugaritic alphabet, probably because these signs were no longer needed for representing Phoenician in the last two centuries of the second millennium BC. When the place of articulation of the following five dental or velar fricatives /x, θ, ð, ðʕ, ɣ/ in Proto-Canaanite had shifted backwards in the oral cavity to merge with /ħ, ʃ, z, sʕ, ʕ/ respectively in Phoenician, the signs that had originally stood for /x_, θ_, ð_, ðʕ_, ɣ_/ became redundant. The redundant signs, except the tooth sign that stood for /θ_/, became obsolete. As for the tooth sign, when /θ/ had merged with /ʃ/, theoretically the sign should have been discarded just as the other four redundant signs. However, for some unknown reason, the Phoenicians used the tooth sign to replace the original sign for /ʃ_/. See Appendix 2.

The Proto-Canaanite alphabet that gave rise to the invention of the Ugaritic alphabet should be a long alphabet with at least 27 signs, not the shorter alphabet with 22 signs as used in Phoenician writing. If the Ugaritic alphabet had originated from the shorter alphabet, the signs in the Ugaritic alphabet would have been arranged as follows: the first 22 signs would have been arranged in the same order as in the Phoenician alphabet, and the remaining five signs would have been appended to the end of the shorter alphabet. But this is not the ordering of the Ugaritic alphabet.

The Phoenician script, which stabilized around 1100-1050 BC, is a direct descendant of Proto-Canaanite. The early Phoenician signs are less pictographic than the early Proto-Canaanite signs, but resemble the late Proto-Canaanite signs. They may look different from the Proto-Sinaitic and early Proto-Canaanite signs, but as sound symbols they are all of the same nature. Like a Proto-Sinaitic or Proto-Canaanite sign, each Phoenician sign stands for cα. It is a syllabic sign with multiple sound values. If it is true that the Phoenician language has eight vowels like Ugaritic, then it can be said that a Phoenician sign stands for eight syllables plus a reduced syllable.[3] Since there are 22 signs in the Phoenician alphabet, the Phoenician signs stand for 176 cα syllables (22c × 8α = 176 cα syllables) plus 22 reduced syllables, i.e., 198 syllables ((22 × 8) σ + 22σ = 198σ). With these 22 signs, the Phoenicians could write all the syllables in their language.

The earliest extant extended Phoenician text is the inscription on Aḥiram’s sarcophagus dated to around 1000 BC. It is already a mature piece of alphabetic Semitic writing. As was said earlier, the Proto-Canaanite alphabet should have been widely used in Phoenicia in the thirteenth century BC. There should be extended Proto-Canaanite texts written in Phoenicia then, but these texts have not been found. If they were written on papyrus or some other perishable material, they may have been lost to us forever.

[1] See Mieroop (2011:126-145).

[2] In this sentence, ‘this kind of alphabet’ refers to any alphabet in which one sign represents several CV syllables with the same onset. In theory, it can be used to write any languages, including even non-Semitic languages, such as Hurrian and Greek. Nevertheless, how appropriate or effective it is for the languages concerned is another matter.

[3] The “reduced syllable” here refers to a consonant followed by a barely audible schwa. It originates from a CV syllable in which V is short. However, this “reduced syllable” is generally regarded as a consonant in a phonemic analysis. See Tables 2 & 3.

7 January 2017

Views: 929