11 The Phoenician way to write a Greek name

As mentioned earlier, it is commonly agreed that the Greeks learnt the alphabet from the Phoenicians. However, despite this consensus about the provenance of the Greek alphabet from the Phoenician signs, scholars differ greatly on when and how the Greeks used the Phoenician signs to write Greek. We believe that proto-Greek alphabetic writing began when the Phoenicians started to write Greek names in their commercial contacts with the Greeks. The Phoenicians exploited the sub-system of writing foreign names in their orthography to denote Greek sounds. When proto-Greek alphabetic writing started, its nature should be no different from that of this sub-system of Phoenician writing. However, the earliest extant Greek alphabetic writing, as inscribed on the Dipylon vase dated to around 740 BC, was already a mature piece of segmental writing. Nobody knows the actual processes by which proto-Greek alphabetic writing evolved into such mature segmental writing as was found on the Dipylon vase, because Greek alphabetic writings that antedate the Dipylon inscription have not yet been found.

When did proto-Greek alphabetic writing begin? Scholars suggest widely different dates, which vary from the 15th to the 8th century BC (Swiggers 1996:267). We believe that it might have taken more than a century for the Greek alphabetic writing to evolve from a syllabic system into a segmental one in the first quarter of the first millennium BC. Some historians of the classical era claimed that the Phoenicians founded the cities of Cadiz in Spain and Utica in Tunisia at the end of the twelfth century BC, but modern historians doubt the truthfulness of their claims, because there is scant archaeological evidence today to support these claims (Culican 1986:952). Despite the lack of physical evidence, one cannot rule out the possibility that the historians of the classical era had based their claims on records now lost to us. According to the modern archaeologist Maria E. Aubet, Phoenician cities like Byblos and Sidon soon recovered after the crisis of 1200 BC caused by the incursions of the Sea Peoples and resumed their commercial activities. At the end of the second millennium contacts between the Greeks and the Phoenicians were most intense (2001:29, 9). The Phoenicians are known to have a long history of seafaring and trading. Their overseas commerce with other lands might have been active during the latter half of the twelfth century BC. If this was the case, then the writing of Greek names by the Phoenicians might have taken place as early as the twelfth century BC when they came into contact with the Greeks en route to the Spanish coasts. In any event, the writing of Greek names by the Phoenicians should have happened no later than the end of the second millennium BC.

In their business transactions with the Greeks, the Phoenicians would need to write down some Greek names, such as the names of the ports of call, their trading partners, and even some produce indigenous to Greece. The Phoenicians might ask the Greeks to say these names slowly and clearly so that they could write them down syllable by syllable by means of Phoenician signs. When writing a Greek name, the Phoenicians would focus on its sound without bothering much about its meaning. As a Phoenician sign is a syllabic sign with multiple sound values, the Phoenicians would be obliged to use a mater to specify its sound value. They would choose the most suitable sign and mater to match as closely as possible each Greek syllable they heard. As there were only twenty-two Phoenician signs and three matres to choose from, the transcriptions might not be able to accurately reflect the Greek pronunciations.

The predominant syllable structure of Phoenician is CV. The CVC structure is also quite common. The Greek syllable structure, however, may comprise CV, CVC, V, and VC. The Phoenicians would not have much difficulty in writing CV syllables in Greek names, but would encounter some difficulty in writing other types of syllables. The written form of a Phoenician sign plus a mater specifically caters to the CV syllable, and so cannot be used conveniently to represent other types of syllable structure without modifications. As the sounds of foreign names need not be very exactly transcribed, the Phoenicians would probably tend to turn the other types of syllable structure into CV or CVCV structures when writing a foreign name. In the transcription of a foreign name, this way of turning its syllable structure to suit one’s own can easily be found in scripts of such languages as Chinese and Japanese today, as these languages have a simple syllable structure like Phoenician’s.

11.1 The Phoenician way to write a Greek CV syllable

To write a Greek CV syllable, the Phoenicians would use a Phoenician sign plus a mater. We first deal with the Phoenician signs used for writing Greek CV syllables in §11.1.1 and then with the matres in §11.1.2.

11.1.1 The Phoenician signs used for writing Greek CV syllables

The earliest extant alphabetic Greek inscriptions, which are dated to the second half of the eighth century BC, can be counted with the fingers of one hand. But in later centuries the number of alphabetic Greek inscriptions increased. By studying the numerous Greek inscriptions of, say, the fifth century BC, one can reconstruct with some certainty the phonological systems of the various Greek dialects spoken in that period. Since this treatise focuses on the time when the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, which we believe occurred probably in the tenth century BC, we have to hypothesize about the vowel and the consonant systems of the Greek dialects spoken then. Despite the lack of inscriptional evidence for the reconstruction of the phonological systems of the Greek dialects spoken in the tenth century BC, one may assume that they should not be drastically different from those in the fifth century BC. Besides, from the Phoenician signs that were first adopted for writing the Greek language, one can still form an idea about the consonant system of the Greek language spoken in the tenth century BC.

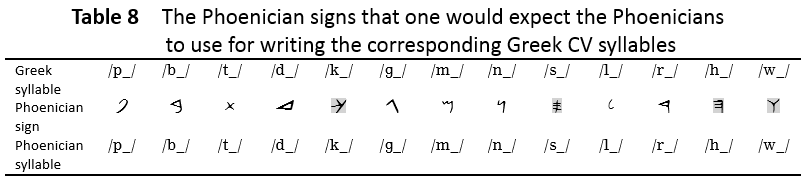

In ancient Greek, most dialects had in common fifteen consonants: /ph, p, b, th, t, d, kh, k, g, m, n, s, dz, l, r/ (Chadwick 1994:1494; Lejeune & Ruijgh 2003: 615). Eleven of them /p, b, t, d, k, g, m, n, s, l, r/ had close counterparts in Phoenician, and so Greek CV syllables beginning with these consonants can readily be represented by the corresponding Phoenician signs. For example, the Phoenician sign <_b>, originally representing the Phoenician /b_/ syllables, would be ready for use to represent all the /b_/ syllables in Greek. Besides the above fifteen consonants, many Greek dialects also had a glottal fricative and a labialized velar approximant: /h/ and /w/. Greek syllables beginning with these two consonants could also be readily represented by the corresponding Phoenician signs <_h> and <_w>, which are meant for writing the Phoenician /h_/ and /w_/ syllables. Table 8 below shows the thirteen Phoenician signs that an outsider would expect the Phoenicians to use at the outset for writing Greek syllables beginning with consonants that had close counterparts in Phoenician:

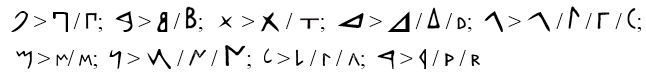

As can be seen from the local scripts of archaic Greece, nine of the above thirteen Phoenician signs did naturally evolve into the corresponding Greek consonant letters: [1]

However, the representation of the Greek /k_/, /s_/, /h_/, /w_/ syllables by these four signs <_k>, <_s>, <_h>, and <_w> (highlighted in Table 8) met with some complications that need to be elaborated on below.

The representation of the Greek /k_/ syllables

How the Phoenicians would write the Greek /k_/ syllables is noteworthy. As can be seen from the Greek inscriptions written in the period from the eighth to the sixth century BC, both the letters <K> (which evolved from the Phoenician sign <_k>) and <Q> (which evolved from the Phoenician sign <_q>) were used to write the Greek consonant /k/. While the Greeks used <Q> to write the onset of the Greek syllables /ku(:)/ and /ko(:)/, they never used it to write the onset of the Greek syllables /ki(:)/, /ke(:)/, and /ka(:)/. To write the onset of the Greek syllables /ki(:)/, /ke(:)/, and /ka(:)/, the Greeks always used the letter <K>. The use of <K> and <Q> to write the Greek consonant /k/ can be seen as circumstantial evidence for the lead that the Phoenicians took in writing archaic Greek. In recording Greek names, the Phoenicians would use the sign <_k> for the Greek /ki(:)/, /ke(:)/, and /ka(:)/ as they would hear these syllables as sounds close to the Phoenician /ki(:)/, /ke:/, and /ka(:)/; however, they would use the sign <_q> for the Greek /ku(:)/ and /ko(:)/, which probably sounded to them like their /qu(:)/ and /qo:/. [k] is a velar stop articulated with the back of the tongue touching the soft palate, whereas [q] is a uvular stop articulated with the root of the tongue touching the very back of the soft palate. It is possible that the place of articulation for the ancient Greek /k/ varied to some extent according to the following vowel: it was further forward before a front vowel and further backward before a back vowel. According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus (c. 60 BC – after 7 BC), a Greek rhetorician, the Greek /k/ is said “with the tongue rising to the palate, near the pharynx” (Petrounias 2007:545). The place of articulation of the ancient Greek /k/ seems to be quite back. /k/ and /q/ are two different phonemes in Phoenician, while a front [k] and a back [k] are allophones in Greek. It seems that the Greek /k/ is realized as a sound close to the Phoenician /k/ when followed by a front vowel but close to the Phoenician /q/ when followed by a back vowel.

If the Greeks had had to write the Greek /ki(:)/, /ke(:)/, /ka(:)/, /ku(:)/ and /ko(:)/ on their own at the outset, they would have used the Phoenician <_k> only to represent all the /k_/ syllables, because to them these syllables all began with the same consonant /k/. They would not have used <_q> to write /ku(:)/ and /ko(:)/. The Phoenicians’ use of <_k> and <_q> to write the Greek /k_/ syllables did not bother the Greeks at the beginning because they knew when to use <_k> and when to use <_q>. However, when the logic of the phonemic principle asserted itself in Greek writing in the sixth century BC, the letter <Q> gradually fell out of use and was replaced by the letter <K>. /ku(:)/ and /ko(:)/ were almost universally written as <ku> and <ko> in Greece in the fifth century BC.

The representation of the Greek /s_/ syllables

The representation of the Greek /s_/ syllables seems to be more complicated than the case above. One would expect that under normal circumstances the Phoenician sign <_s> sāmekh would be used to write the Greek /s_/ syllables because <_s> represents the Phoenician /s_/ syllables. But in the local scripts of archaic Greece, the letter that was used to write the Greek /s/ was <Σ> sigma or <М> san, not the Greek letter <Ξ> that evolved from the Phoenician sign <_s> sāmekh. The Greek name sigma, however, vaguely suggests a link with the Phoenician name sāmekh. Some scholars believe that the name sigma was derived from sāmekh. If this is the case, it might imply that the Phoenician sign <_s> sāmekh had once been used to write the Greek /s_/ syllables before it was abandoned by the mid-eighth century BC. We therefore think it possible that the sign <_s> (sāmekh, later called by the Greeks sigma) had been used at the outset to write the Greek /s_/ syllables before it was replaced by the sign <Σ> sigma, which we believe had evolved from the Phoenician sign <_ʃ> shin.

As regards the letter <М> san in the local scripts of archaic Greece, we believe that it evolved from the Phoenician sign <_ʃ> shin. The letter <М> san suggests a stronger link with the Phoenician sign <_ʃ> shin with respect to both name and shape. Since Greek had only one sibilant: /s/, the Phoenician name shin would naturally become sin in Greek, which later evolved into san. With respect to shape, the Greek letter <М> and the Phoenician sign <_ʃ> apparently can be related. The sign <_ʃ>, when turned upside down, became <М>. There is evidence to suggest that <М> probably originated from <_ʃ>. In two local abecedaries of Corinth and Kroton dated c. 600-550 BC and c. 475-450? BC respectively (Jeffery 1961: Plate 20:16; Plate 50:19), the letter <М> san appears between <R> and <T>, just as the Phoenician sign <_ʃ> shin is located in the alphabet between <_r> rho and <_t> tau. If it is true that <М> san originated from <_ʃ> shin, that means that san would naturally retain shin’s position in the abecedaries and that <_ʃ> was probably used to write the Greek /s_/ syllables at one time. Why did the Phoenicians use <_ʃ>, which should stand for /ʃ_/, to write the Greek /s_/ syllables? The reason may be that some of the Greek /s_/ syllables sounded like their /ʃ_/ syllables. It is possible that the Phoenicians used both <_s> and <_ʃ> to write the Greek /s_/ syllables.

Judging from the way in which the Cantonese /s_/ syllables are written in modern Arabic, we believe that it was possible for the Phoenicians to use not only <_s> and <_ʃ> but also <_ʕs> to write the Greek /s_/ syllables. It should be noted here that Cantonese, like archaic Greek, has only one sibilant phoneme, namely /s/. When requested to write out in Arabic letters the sounds of some Cantonese words read out to him, our teacher of Arabic, under the influence of his mother tongue Egyptian Arabic and constrained by the nature of the Arabic script, wrote the Cantonese syllables beginning with /s/ in the following three words as follows: 思/si/ سي, 書/sy/ شيو, 山/san/ صان. The Arabic transcriptions, if rendered in IPA symbols, would become: سي /si:/, شيو /ʃi:w/, صان /sʕa:n/. The Arabic letters ش ,س and ﺼ represent /s_/, /ʃ_/, and /sʕ_/ respectively. It can be seen from here that the Cantonese phoneme /s/ was perceived as three different sounds /s/, /ʃ/ and /sʕ/ by our Arabic teacher. His perception of the Cantonese /s/ as three different sounds might be due to the fact that the sound of /s/ is affected by the vowel that follows it. The vowel /i/ in the Cantonese syllable /si/ is close, front, and unrounded like the vowel /i:/ in the English word see; the vowel /y/ in the Cantonese syllable /sy/ is close, front, and rounded like the vowel /y:/ in the German word für and the French word sûr; the vowel /a/ in the Cantonese syllable /san/ is open and back like the vowel /ɑ:/ in the English word father. Hence our Arabic teacher used three different Arabic letters ش ,س and ﺼ to transcribe the Cantonese /s_/ syllables.

The Arabic letters ش ,س and ﺼ can be regarded as the respective counterparts of the Phoenician signs <_s>, <_ʃ>, and <_ʕs>: while <_s> and س denote /s_/, <_ʃ> and ش denote /ʃ_/, and <_ʕs> and ص denote /sʕ_/ (see Appendix 2). Just as the Arabic letters ش ,س and ﺼ can be used to write the Cantonese /s_/ syllables, so the Phoenician signs <_s>, <_ʃ>, and <_ʕs> could be used to write the Greek /s_/ syllables. If it is true that the Phoenicians used three different signs <_s>, <_ʃ>, and <_ʕs> to write the Greek /s_/ syllables at the outset, it was probably the Greeks who decided to make the representation of /s_/ simple by using only one sign later on, after grasping the Phoenician alphabet. Judging from the local scripts of archaic Greece, the Greeks seemed to have chosen the sign <_ʃ> to represent /s_/.

Two other probable modern parallels of the Phoenicians’ use of <_s> and <_ʃ> to write the Greek /s_/ syllables can be found in the English speakers’ use of <s_> and <sh_> to transcribe the /s_/ syllables in Japanese and Cantonese. The Japanese syllables /sa/, /su/, /se/, and /so/ are written as <sa>, <su>, <se>, and <so> respectively while /si/, /sja/, /sju/, and /sjo/ are written as <shi>, <sha>, <shu>, and <sho> in the Hepburn system, named after the American missionary James Curtis Hepburn. To Hepburn, the Japanese /si/ and /sj_/ sounded like the English /ʃi/ and /ʃ_/. Japanese scholars, however, uniformly wrote their /s/ phoneme with <s>, as shown by the Nihon-shiki and kunrei-shiki systems. Under these systems, the Japanese /si/ and /sj_/ are written as <si> and <sy_>. As regards Cantonese, the /s_/ syllables with a rounded front vowel are often written by the British as <sh_>. For example, the syllables /syt/ and /sœn/ are often written as <shuet> and <shun>. Even the syllables /sa/ and /san/ are often written as <sha> and <shan>, for unknown reasons. It is not very surprising, therefore, that the Phoenicians took some of the Greek /s_/ syllables for their /ʃ_/ syllables and so used <_ʃ> to write them.

The letter <Σ> sigma in the local scripts of archaic Greece, we believe, is a variant form of <_ʃ> (shin > sin > san), not a descendant of <_s> (sāmekh > sigma). <_ʃ>, when turned 90˚ anti-clockwise, became <Ȝ>, and then <Σ> when written boustrophedon. <Ȝ> or <Σ>, accordingly, should have been called san too. Why was it called sigma instead? One possible reason is that the name sigma, being commonly accepted as the name of the sign <_s> for writing the /s_/ syllables, had persisted from force of habit even after the original sign <_s> had been replaced by <Ȝ>.

As was said earlier, it is possible that the Phoenicians used three different signs <_s>, <_ʃ>, and <_ʕs> to write the Greek /s_/ syllables and that the Greeks decided later on to make their writing easier by using only one sign for this purpose. It is not very clear why <_ʃ> was preferred. One possible reason is that <_ʃ> was the easiest to write. The shape of <_ʕs> is not symmetrical enough for a beginner to learn it as easily as the other two signs <_s> and <_ʃ>, which are more regular and symmetrical in shape. <_ʃ> was preferred to <_s>, possibly because <_ ʃ> can be written in a single stroke without lifting the pen while <_s> has to be written in four strokes.

The Greek historian Herodotus reported in the late fifth century BC that the same letter was called san by the Dorians and sigma by the Ionians (Histories 1.139). It is possible that by ‘the same letter’ Herodotus meant the letter <Σ>, which was variously called san and sigma in different Greek regions. Regions that called <Σ> san might have come under the influence of those regions that called <Σ> sigma and so would gradually come to call <Σ> sigma too. The name sigma finally came to replace the name san and was adopted as the proper name for the letter <Σ>. It should be noted that to the Phoenicians, the shape of a Phoenician sign, however abstract, could still be considered motivated because the name of a Phoenician sign still reminded them of the object that the name stood for, but to the Greeks, the relation between the shape of a Phoenician sign and its name was basically arbitrary. Thus the Greeks could freely associate the name sigma with the letter <Σ>. Though called sigma, the letter <Σ> still retained shin’s position in the alphabet.

The representation of the Greek /h_/ syllables

One would expect the Phoenicians to use the sign <_h> he to write the Greek /h_/ syllables because <_h> represents the Phoenician /h_/ syllables. But in the local scripts of archaic Greece, the letter that was used to write the Greek /h/ was <H> (which evolved from the Phoenician sign <_ḥ> ḥēth), not <E> (which evolved from the Phoenician sign <_h> he). In Phoenician, while the sign <_h> is meant for writing the /h_/ syllables, the sign <_ḥ> is meant for writing the /ħ_/ syllables. Why was the sign <_ḥ> used to write the Greek /h_/ syllables instead of the sign <_h>?

Judging from the way in which the Cantonese /h_/ syllables are written in Arabic letters, it is possible that the Phoenicians used both the signs <_h> and <_ḥ> to write the Greek /h_/ syllables. Our Arabic teacher wrote in Arabic letters the following four Cantonese words (all beginning with /h/) read out to him as follows: 希 /hei/ → حِي /ħi:/; 哈 /ha/ → حَا /ħa:/; 圈 /hyn/ → هُوﻦ /hu:n/; 開 /hɔi/ → هُویّ /hu:j/. The letters ح (written as ﺤ at the beginning of a word) and ه (written as ﻫ at the beginning of a word) represent /ħ_/ and /h_/ respectively. It can be seen from here that the Cantonese phoneme /h/ was perceived as two different sounds /ħ/ and /h/ by our Arabic teacher. The Arabic letters ح and ه can be regarded as the respective counterparts of the Phoenician signs <_ḥ> and <_h> : while <_ḥ> and ح denote /ħ_/, <_h> and ه denote /h_/ (see Appendix 2). Just as the Arabic letters ح and ه can be used to write the Cantonese /h_/ syllables, so the Phoenician signs <_ḥ> and <_h> could be used to write the Greek /h_/ syllables.

If it is true that the Phoenicians used both <_ḥ> and <_h> to write the Greek /h_/ syllables at the outset, why did the Greeks eventually use <_ḥ> only to represent their /h_/ syllables? One possible reason is that at a later stage of the development of the Greek alphabetic writing system, the Greeks found it necessary to create a new mater for rhyming with syllables ending in /e(:)/ or /ɛ:/. Since the name of the Phoenician sign <_h> was /e:/ (or /ɛ:/) in some Greek regions and /he:/ (or /hɛ:/) in others (this point will be elaborated in §13), it was a strong candidate for the new mater in the alphabet. The Greeks finally chose the sign <_h> as the new mater for rhyming with syllables ending in /e(:)/or /ɛ:/. Hence the Greeks used the sign <_ḥ> to represent the Greek /h_/ syllables while using the sign <_h> exclusively as a mater. The use of <_h> as a mater, we believe, is a turning point in the evolution of the Greek writing system. This point will be elaborated on in §12.3.

The representation of the Greek /w_/ syllables

The representation of the Greek /w_/ syllables does not seem to be very complicated. One would expect the Phoenicians to use the sign <_w> waw to write the Greek /w_/ syllables because <_w> represents the Phoenician /w_/ syllables. But in the local scripts of archaic Greece, the letter that was used to write the Greek /w/ was <F> wau / digamma, not <Y> (which evolved from the Phoenician sign <_w> waw). Why? The reason is not difficult to understand if one realizes that <F> is in fact just a variant form of <Y>. We believe that initially, the Phoenician sign <_w> was probably used both as a mater and as an ordinary or normal sign that represented the Greek /w_/ syllables. Later, when its variant form <F> was used as an ordinary sign that stood for /w_/, <Y> could then be used exclusively as a mater.

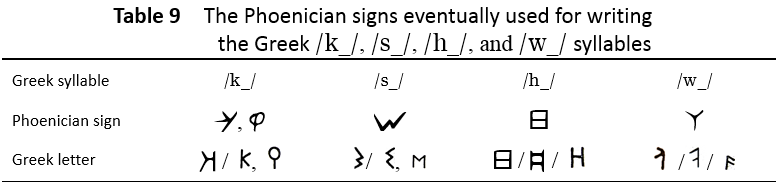

The Phoenician signs eventually used for writing the Greek /k_/, /s_/, /h_/, /w_/ syllables

The Phoenician signs eventually used for writing the Greek /k_/, /s_/, /h_/, /w_/ syllables are listed in Table 9 below. The Greek letters in the third row evolved from the Phoenician signs in the second row.

The Phoenician signs used for writing Greek CV syllables that had no close counterparts in Phoenician

As was said at the beginning of §11.1.1, many Greek dialects had seventeen consonants, thirteen of which had close counterparts in Phoenician. In other words, archaic Greek had four consonants which did not exist in Phoenician. These four consonants are /ph, th, kh, dz/. How did the Phoenicians write the Greek CV syllables beginning with these consonants? We first deal with the syllables beginning with the aspirated stops /ph, th, kh/.

The Phoenician signs used for writing Greek syllables beginning with /ph, th, kh/

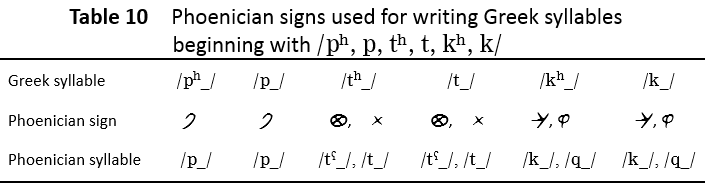

Phoenician had six stops /p, t, k, b, d, g/ while archaic Greek had, besides these six stops, three more, namely /ph, th, kh/. This being the case, the Phoenicians probably heard the Greek syllables beginning with /ph, th, kh/ as sounds closest to their /p_, t_, k_/ syllables. Since the Phoenicians used <_p>, <_t>, and <_k> to represent their /p_, t_, k_/ syllables respectively, one would expect them to use these signs to represent the Greek /ph_, th_, kh_/ syllables too. As can be seen from the local scripts of archaic Greece, the letters <P> and <K>, which evolved from the Phoenician signs <_p> and <_k>, were used just as expected to represent not only /p/ and /k/ but also /ph/ and /kh/. However, the letter <Θ> (which evolved from the Phoenician sign <_ʕt>) was used to represent /th/ instead of the expected <T> (which evolved from the Phoenician sign <_t>). This means that the Phoenician sign <_ʕt> was used to represent the Greek /th_/ syllables. Why did the Phoenicians use the sign <_ʕt> to write the Greek /th_/ syllables?

Judging from the way in which the /th_/ and /t_/ syllables in foreign names are written in modern Arabic, it was possible for the Phoenicians to use both the signs <_t> and <_ʕt> to write the Greek /th_/ and /t_/ syllables. The respective Arabic counterparts of the Phoenician signs <_t> and <_ʕt> are ت and ط. While <_t> and ت denote /t_/, <_ʕt> and ط denote /tʕ_/ (see Appendix 2). In modern Arabic the /th_/ and /t_/ syllables in foreign names are written generally as ت (read as /t_/) and occasionally as ط (read as /tʕ_/). For example, the /th_/ syllables in the following English names and the /t_/ syllables in the following French names are written in modern Arabic by the letter ت /t_/ (written as ﺘ at the beginning of a word): Tony توني, Newton نيوتن; Toussaint توسان, Étienne إتيان. Nevertheless, the /th_/ and /t_/ syllables in some names are written by the letter ط /tʕ_/: Washington واشنطن, Italia ايطاليا, Αριστοτέλης (Aristoteles) أريسطوطلس, Augustus أغسطس. The /th_/ and /t_/ syllables in foreign names are written in modern Arabic as either ت or ط, possibly because the /th/ or /t/ phoneme in these syllables is perceived as two different sounds by the native speakers of Arabic. Some /th_/ and /t_/ syllables are heard as sounds close to their /t_/ syllables, and so the letter ت is used to denote these sounds; some /th_/ and /t_/ syllables are heard as sounds close to their /tʕ_/ syllables, and so the letter ط is used to denote these sounds.

Our Arabic teacher wrote the Cantonese syllables with the initial consonant /th/ in the following three words as ت /t_/: 湯 /thɔŋ/ تونغ, 天 /thin/ تِن, 太 /thai/ تاي. However, he wrote the Cantonese word 灘 /than/ as طان /tʕa:n/. His pereption of the Cantonese word /than/ as a sound close to the Arabic /tʕa:n/ might be due to the fact that in the word /than/, the sound /th/ is affected by the following vowel /a/, which is open and back like the vowel /ɑ:/ in the English word father.

The use of ت and ط to write the /th_/ and /t_/ syllables in foreign names in modern Arabic indirectly supports the hypothesis that it was possible for the Phoenicians to use both the signs <_t> and <_ʕt> to write the Greek /th_/ and /t_/ syllables. In Table 10 below are listed the signs that the Phoenicians probably used to write the Greek syllables beginning with the six voiceless stops /ph, p, th, t, kh, k/ :

If it is true that the Phoenicians used both the signs <_t> and <_ʕt> to write the Greek /th_/ and /t_/ syllables, then two problems would arise in the writing and reading of Greek. In writing /th_/ and /t_/, the Greeks would have to decide whether to use the sign <_t> or <_ʕt>. In reading the sign <_t> or <_ʕt>, the Greeks would have to decide whether it represented /th_/ or /t_/. To make life easier, the Greeks probably decided eventually to use only <_ʕt> to write /th_/ and only <_t> to write /t_/. Consequently, as can be seen from the scripts of archaic Greece, <T> denoted only /t/, and <Θ> only /th/.

The Phoenician sign used for writing Greek syllables beginning with /dz/

The Phoenician sign <_z> zayin, we believe, was used to represent the Greek /dz_/ syllables. According to the British linguist W. Sydney Allen, at the time when the Greeks adopted the Semitic alphabet, the sign <_z> probably represented the Greek affricate /dz/, which later underwent metathesis in early Greek to become /zd/. The archaic Greek affricate /dz/, Allen argues, probably evolved from a coalescence of /dj/ in Indo-European. How /dj/ could evolve into /zd/ through /dz/ may be illustrated by the possible route of evolution taken by the Indo-European word *ped-yos (1974:53-55):

*ped-yos /pedjos/ > archaic Greek */pedʒos/ > */pedzos/ > early Greek πεζός /pezdos/

Thus, according to Allen, the Phoenician sign that is transliterated in this treatise as <_z> was probably read as /dz/ in archaic Greek, and later as /zd/ in early Greek. The coalescence of /d/ and /j/ to become /ʤ/ is a common phenomenon in many languages, and metathesis may arise occasionally in some languages. For example, the English words waps and þrid (thrid) underwent metathesis to become wasp and third.

There is no doubt that the Greek letter that evolved from the Phoenician sign <_z> was read as /zd/ in early Greek because this is supported by inscriptional evidence. One might wonder whether the affricate /dz/ had already evolved into /zd/ at the time when the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet. The Phoenician sign <_z>, we believe, was used to write the Greek /dz_/ syllables at the time when the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, not /zd_/. If there had been Greek words or syllables beginning with /zd/ then, the Phoenicians might have used the signs <_z> zayin plus <_d> dāleth to represent the sound /zd_/, whereas the Greeks might have used the signs <_s> sāmekh plus <_d> dāleth.[2]

If it is true that word-initial /dz/ had not yet evolved into /zd/ in the Greek language at the time when the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, which Phoenician sign or signs would be used to represent /dz_/? If the Greeks had had to write /dz_/ on their own after learning the Phoenician alphabet, they might have had difficulty choosing a suitable Phoenician sign to represent syllables beginning with /dz/ because there is no Phoenician sign that represents syllables beginning with this affricate sound. Judging from the fact that the sign <_z> zayin was chosen to write the Greek /dz_/ syllables, it was probably the Phoenicians who chose this sign, not the Greeks, for the following reasons.

If the Greeks had had to write their /dz_/ on their own, different Greeks might have chosen different Phoenician signs. If the Phoenicians had to write the Greek /dz_/, probably they would generally use the sign zayin <_z> only. Under the influence of their mother tongue, the Phoenicians would probably perceive the Greek sound /dz_/ as a sound closest to the Phoenician /z_/ and so would use the sign <_z> zayin to represent /dz_/. The Phoenicians would tend to miss the initial /d/ in their perception of the Greek word-initial /dz/, just as native Arabic speakers today tend to miss the initial /d/ in their perception of the Italian word-initial /dz/. The Arabic speaker’s perception of the Italian /dz/ is probably a modern parallel of a Semitic speaker’s perception of the Indo-European word-initial /dz/. The Italian name Zola /dzɔ:la/, for example, is transliterated today in Arabic as زولا <aɁ_l uw_z> (Arabic transliterations to be read from right to left hereafter in accordance with the direction of Arabic writing) /zu:la/. The initial /d/ in /dzɔ:la/ is ignored in the Arabic transliteration, which means that the initial /d/ is either missed or considered to be too different from the Arabic /d/ or any other Arabic consonant to be so identified. Allen’s hypothesis about the existence of the Greek affricate /dz/ at the time when the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet is probably correct.

Jeffery points out that in Thera the Greek letter that evolved from the Phoenician sign <_s> was used to represent /dz/ instead of the Phoenician sign <_z> (1961: 317). The Greek affricate /dz/ spoken in Thera might have been less voiced than in other dialects and so was perceived by the Phoenicians as /s/. Hence the Phoenicians used the sign <_s> meant for writing /s_/ to represent the Theran /dz_/ syllables. It goes without saying that the Therans would read the sign <_s> as /dz_/.

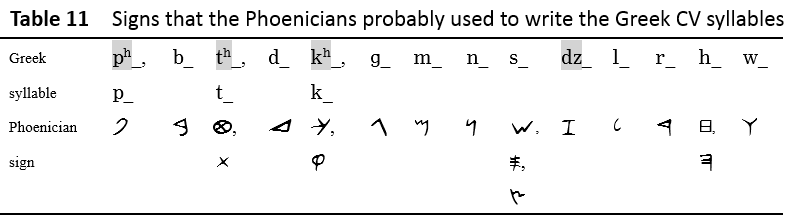

The Phoenician signs used to write the Greek CV syllables: a sum-up

To write a Greek CV syllable, the Phoenicians would use a Phoenician sign plus a mater. Table 11 below shows the eighteen different Phoenician signs that the Phoenicians would use when writing the Greek CV syllables. The highlighted Greek syllable onsets /ph/, /th/, /kh/, and /dz/ did not exist in Phoenician, and the Phoenician signs <_s>, <_ʕs>, and <_h> representing /s_/ and /h_/ were discarded later on by the Greeks, while <_ʕt> and <_t> were used to represent /th_/ and /t_/ respectively.

The importance of the Phoenicians’ perception of Greek sounds

In regard to the genesis of the Greek alphabet, the Phoenicians’ perception of Greek sounds seems to have been overlooked. If one allows for the possibility of the Phoenicians’ leading role in writing the Greek sounds at the earliest stage of Greek alphabetic writing, one can account for the choice of the Phoenician signs for writing Greek syllables as listed in Table 11. One can also explain why the local scripts of archaic Greece, if they started with the signs as listed in Table 11 at the earliest stage, could end up with such signs as presented in Jeffery’s Table of Letters (1961: at end).

Although the correspondence between the Greek and Phoenician consonants is close, it is not always an easy one-to-one correspondence. A Greek consonant may be heard by the Phoenicians as different sounds corresponding to two or even three Phoenician consonants, and two different Greek consonants may be heard as the same sound corresponding to one Phoenician consonant. Thus the Phoenicians might have used two or three signs to represent Greek syllables beginning with the same consonant, and only one sign to represent Greek syllables with different initial consonants, as can be seen from Table 11 above.

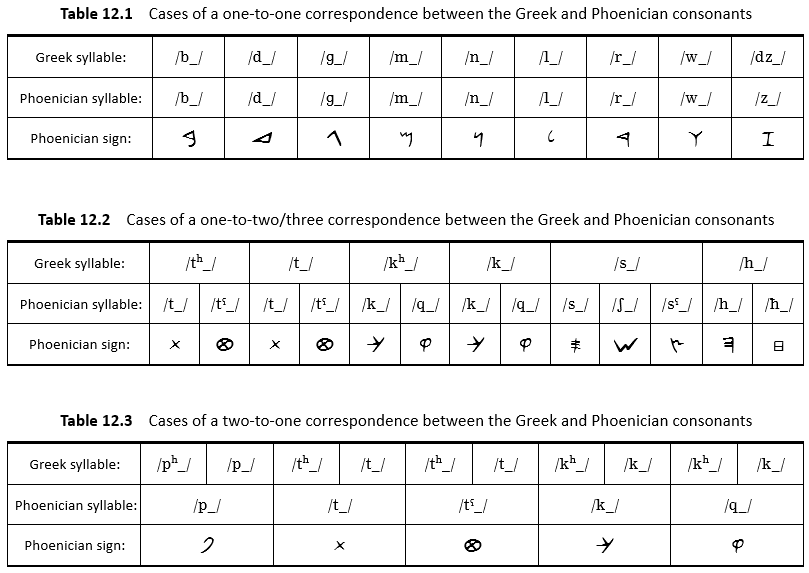

One can perceive from this section (§11.1) that there are three kinds of correspondence between the Greek and Phoenician consonants, which will be shown in Tables 12.1, 12.2 and 12.3 below. The first row of each table shows the Greek syllables to be written by the Phoenicians; the second row shows the Phoenician syllables that correspond to the Greek syllables in the first row; the third row shows the Phoenician signs that the Phoenicians would use to write the corresponding Greek syllables in the first row.

11.1.2 The Phoenician way of using matres to write Greek CV syllables

As was said earlier, the Phoenicians would use a Phoenician sign plus a mater to write a Greek CV syllable. We argued earlier in this treatise that the Phoenicians had three matres <aʔ>, <ij>, and <uw>. Which mater to use would depend on the V of the Greek CV syllable to be written.

Ancient Greek has many more vowels than Phoenician. As was said earlier, Phoenician possibly had only eight monophthongs: /a(:), i(:), u(:), e:, o:/. Ancient Greek, however, had not only a lot of monophthongs, but also quite a lot of diphthongs.

Ancient Greek had 10-12 monophthongs, subject to dialect variation. Some dialects had ten monophthongs, which are generally transcribed as: /a(:), i(:), u(:), e(:), o(:)/. Five of the monophthongs were short, and five were long. The quality of a short monophthong is presumed to be basically the same as that of a long monophthong. It should be noted that the mid vowels /e(:), o(:)/ might be realized as vowels that lay somewhere between [e:, o:] and [ɛ:, ɔ:]. If /e(:), o(:)/ were realized as vowels that were closer to [ɛ:, ɔ:] than to [e:, o:], then /e(:), o(:)/ could well be transcribed as /ɛ(:), ɔ(:)/. It is also possible that in some dialects the short mid vowels differed in quality from the long mid vowels. The short and long mid vowels might differ so much in quality that they could be regarded as different vowel qualities. In such cases, the short mid vowels can be transcribed as /e, o/ and the long mid vowels as /ɛ:, ɔ:/. Some Greek dialects had twelve monophthongs, which are generally transcribed as /a(:), i(:), u(:), e(:), o(:), ɛ:, ɔ:/ (Malikouti-Drachman 2007:526: Teffeteller 2006:150: for the tongue position for the vowels, see Figure 60 in Petrounias 2007:558).

Ancient Greek had 10 diphthongs, which are generally transcribed as: /ei, ɛ:i, ai, a:i, ui, oi, ɔ:i, eu, au, ou/. Generally speaking, these diphthongs were not used as frequently as the monphthongs.

A Greek CV syllable may consist of a consonant plus a monophthong or a diphthong. To represent this type of syllable, the Phoenicians would use a Phoenician sign plus a mater.

Regarding the choice of matres in representing a CV syllable, it is the timbre or quality of the vowel that would determine which mater to use to represent the syllable, not the length of the vowel. Thus, regardless of the length of the V in the CV, the Phoenicians would use the same mater as long as the quality of V remained the same.

If the initial C of a Greek CV syllable is /n/, it is possible in theory for it to combine with each of the above monophthongs or diphthongs to form the following twenty-two syllables: /na(:), ni(:), nu(:), ne(:), no(:), nɛ:, nɔ:, nei, nɛ:i, nai, na:i, nui, noi, nɔ:i, neu, nau, nou/. How would the Phoenicians write such syllables in a Greek name? How would they decide on which mater to use after the sign <_n> /n_/?

As the Phoenicians had only three matres in their alphabet, they could write the above twenty-two syllables only in these three written forms: <aʔ_n>, <ij_n>, and <uw_n>, which they would read basically as /na(:)/, /ni(:)/, and /nu(:)/ respectively. However, as the Phoenicians probably had /e:/ and /o:/ apart from /a(:)/, /i(:)/ and /u(:)/, they would hear the Greek syllables /ne:/ and /ni:/ as two distinct syllables, and so would they hear the Greek syllables /no:/ and /nu:/. If they had to write a foreign speech sound that was close to their /ne:/, they would be obliged to write it as <ij_n>, since the /ni(:)/ sound of <ij_n> was the closest to this foreign speech sound, not the /nu(:)/ sound of <uw_n>, nor the /na(:)/ sound of <aʔ_n>. A problem, however, might arise when they read back <ij_n> sometime later. If they remembered the original sound correctly, they would probably read <ij_n> as /ne:/. If they could not remember the original sound, they might read it as /ni:/. In other words, the Phoenicians might sometimes read <ij_n> as /ne:/ apart from /ni(:)/. By the same token, they might sometimes read <uw_n> as /no:/ apart from /nu(:)/. Thus it is possible that <ij_n> and <uw_n> each basically had two readings while <aʔ_n> had one reading only.

If the above hypothesis is correct, then in writing a CV syllable beginning with /n/ in a foreign name, the Phoenicians would compare this sound with their /na(:)/, /ni(:)/, /nu(:)/, /ne:/, and /no:/ syllables. Any sound that was close to their /na(:)/ would be written as <aʔ_n>; any sound that was close to their /ni(:)/ or /ne:/ would be written as <ij_n>, and any sound that was close to their /nu(:)/ or /no:/ would be written as <uw_n>. The Phoenician way of writing foreign speech sounds had probably become a method of sound comparison, which was one step beyond the rhyming principle governing the use of matres.

The Phoenician sounds /na(:)/, /ni(:)/, /nu(:)/, /ne:/, and /no:/ were possibly the yardsticks against which the above twenty-two Greek syllables were to be measured when the Phoenicians had to decide which of the above three written forms to use in writing these syllables. They would have no difficulty in writing /na(:)/, /ni(:)/, and /nu(:)/, because the three matres rhyme readily with these syllables. As to the remaining syllables, none of the three matres rhyme easily with them, but even so they would have to decide which of the three written forms <aʔ_n>, <ij_n>, and <uw_n> could best represent these syllables. For example, they might use <ij_n> for /nɛ:/ by reasoning like this: since the Phoenician sound /ne:/ of <ij_n> was the closest to the Greek sound /nɛ:/, they could write /nɛ:/ as <ij_n>. They would probably write the other syllables by using the same method of sound comparison. As there are no surviving written records to show how the Phoenicians wrote a Greek name, we have to resort to a modern Semitic script to explore the possible ways in which the Phoenicians would set about writing it.

The Arabic script is a good choice for this purpose as Phoenician and Arabic are both Semitic languages, and as the Phoenician writing system probably has three matres, just like Arabic. The native Arabic speakers’ perception of the sounds of a foreign name and their choice of matres might shed some light on the possible way in which the Phoenicians perceived and wrote a Greek sound. It must be stressed here that the Phoenician vowel system is not the same as that of modern Arabic: while Phoenician possibly has eight monophthongs /a(:), i(:), u(:), e:, o:/, Classical Arabic has only six monophthongs /a(:), i(:), u(:)/ and two diphthongs /ai, au/. The Phoenician consonant system is not the same as that of modern Arabic either, despite many similarities. Thus the Phoenicians’ perception of foreign speech sounds may not be entirely the same as that of the Arabic speakers. Even so, the Arabic speakers’ perception of similar sounds in foreign languages is a useful source of reference in estimating how the Phoenicians would write the above-mentioned twenty-two Greek CV syllables. We may be able to infer the Phoenician way of writing foreign speech sounds by trying to see how these sounds are actually written in Arabic. We will deal with the Phoenician way of writing those Greek syllables containing monophthongs first and then those containing diphthongs later, as the latter case is more complicated.

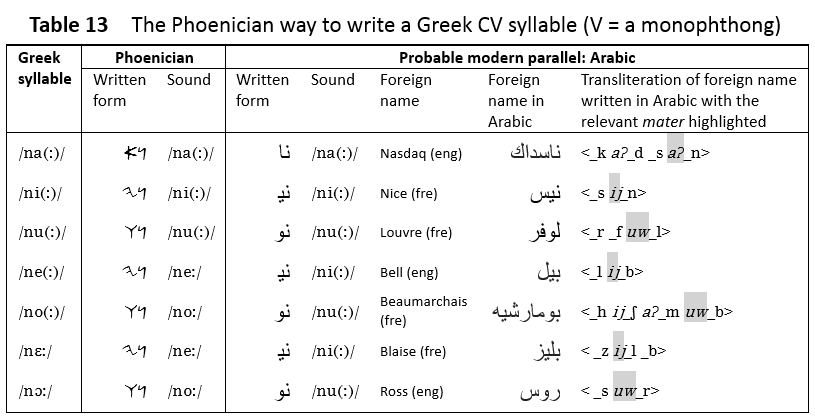

Table 13 below shows how the Phoenicians would write a Greek CV syllable in which V is a monophthong. Based on how similar syllables in a foreign name are written in Arabic, we assume that eventually the Phoenicians would write these syllables with the three matres as shown in the second column of the table. As can be seen from the table below, the Arabic letter ن /n_/ (written as ﻨ at the beginning of a word) is the counterpart of the Phoenician sign <_n> /n_/. The Arabic letters ﮃ ,ﺎ, and و are the respective counterparts of the Phoenician matres <aʔ>, <ij>, and <uw>.

As can be seen from the above table, the Phoenicians might eventually use <aʔ_n> for the Greek syllable /na(:)/,<ij_n> for /ni(:), ne(:), nɛ:/, and <uw_n> for /nu(:), no(:), nɔ:/. The Phoenicians might read <ij_n> as /ni:/ or /ne:/, and <uw_n> as /nu:/ or /no:/. However, as Classical Arabic, like ancient Egyptian, basically has only three vowels (discounting vowel length): /a, i, u/, ﻨﯿ and نو, the counterparts of <ij_n> and <uw_n>, have basically only one reading each. They are read as /ni(:)/ and /nu(:)/ respectively.

As foreign names containing the syllables /nu(:), ne(:), no(:), nɛ:, nɔ:/ are hard to find, we are obliged to use as examples those foreign names containing syllables with the same rhymes. Even so, we can see from these examples which matres modern Arabic would use if it had to write the syllables /nu(:), ne(:), no(:), nɛ:, nɔ:/ in foreign names.

It should be noted that in the table above the sounds /lɛ/ and /rɔ/ in the names Blaise and Ross are written in Arabic as لي and رو, which are transliterated as <ij_l> and <uw_r> in this treatise. The written forms لي and رو here are read in Arabic as /li:/ and /ru:/, which are quite different from the original sounds /lɛ/ and /rɔ/.

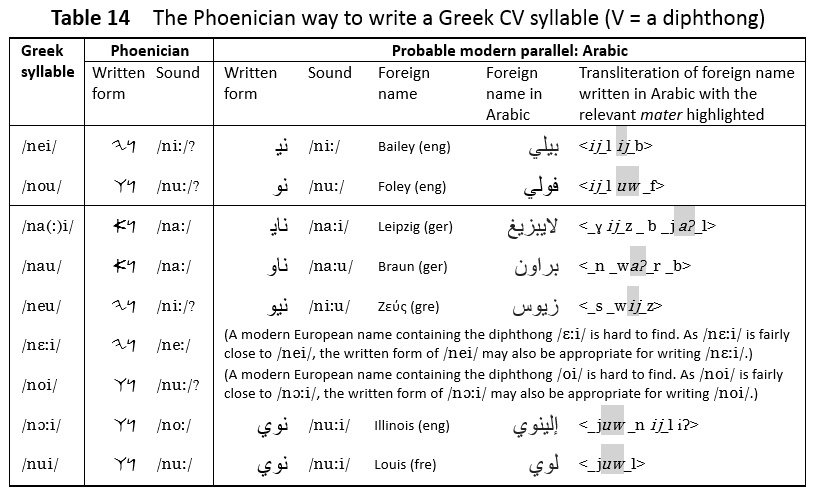

We now deal with those Greek syllables containing a diphthong. In the left-hand column of Table 14 below are listed ten Greek syllables each containing a diphthong. In writing out these ten syllables, the Phoenicians would probably compare these sounds with the five Phoenician syllables having the same onset: /na:, ni:, nu:, ne:, no:/, just in the same manner as they would write those Greek syllables containing a monophthong. How the Phoenicians might write these ten syllables and read their written forms is shown in the second column of Table 14. A question mark (?) next to the sound means that it is uncertain how the Phoenicians would read the written form.

The Phoenicians would probably not be able to analyse the sound of a diphthong in the same manner as modern Arabic does. This should not be very surprising as the Arabic script has benefited from the knowledge of sound analysis accumulated during its long history of development. The Phoenicians would probably be obliged to use the method of sound comparison in writing out a Greek syllable containing a diphthong. They would try to find out which of the five relevant Phoenician syllables /_a:, _i:, _u:, _e:, _o:/ was aurally the closest to this syllable. Take the Greek syllable /nei/ for example. They would compare /nei/ with the five Phoenician syllables /na:, ni:, nu:, ne:, no:/ in order to decide which of the five Phoenician syllables was the closest to /nei/. To the Phoenicians, the Greek /nei/ might sound the closest to either their /ni:/ or /ne:/, depending on the actual sound value of the Phoenician /e:/. If the Phoenician /e:/ sounds like the first vowel of the French word été, the Phoenicians might hear the Greek /nei/ as a sound that their /ne:/ was the closest to. They might then write it as <ij_n> and read <ij_n> as /ne:/. On the other hand, if the Phoenician /e:/ sounds like the first vowel of the French word être, the Phoenicians might hear the Greek /nei/ as a sound that their /ni:/ was the closest to. They might then write it as <ij_n> and read <ij_n> as /ni:/. As was said earlier, how the Phoenicians might write a Greek syllable containing a diphthong and read the written form is shown in the second column of Table 14. As the actual sound values of the Phoenician /e:/ and /o:/ are uncertain, we are not quite sure how the Phoenicians would read the written forms <ij_n> and <uw_n> in the second column of Table 14. As can be seen from Table 14, the Phoenician way of writing a syllable containing a diphthong is generally quite different from the Arabic one.

11.2 The Phoenician way to write a Greek CVC syllable

How would the Phoenicians write a Greek name with a CVC syllable structure, such as /nesto:r/? They might write a CVC syllable initially as: Sign1 + Mater1 + Sign2 + Mater2, thus turning the CVC structure into CVCV. They might write the first CVC syllable /nes/ as <ij_s ij_n>, and read it as /ne:si/ or /ni:si/. The Phoenicians might write the /s/ sound as <ij_s>, because they might hear the Greek /s/ as a sound that the /si(:)/ sound of <ij_s> was the closest to. On the other hand, the Phoenicians might sooner or later come to realize that, if they dropped the last mater, the CVC syllable would be more accurately represented, because in Phoenician writing the sign <_s> sometimes stood for /s/ followed by a barely perceptible schwa. In other words, when not followed by a mater, <_s> would be read as /s/ followed by a barely perceptible schwa. Likewise, they might write the second CVC syllable /to:r/ initially as <aʔ_r uw_t> /to:ra/ or /tu:ra/, and eventually as <_r uw_t> /to:r/ or /tu:r/. To the Phoenicians, the norm for writing a Greek CVC syllable would ultimately be: Sign1 + Mater1 + Sign2. Sign2 could be read as a light and short sound, albeit with different degrees of accentuation. This sound, if analysed phonemically, can be regarded as a C followed by a barely audible schwa or no schwa. It goes without saying that the way to read Sign2 should conform to the Phoenician phonological system.

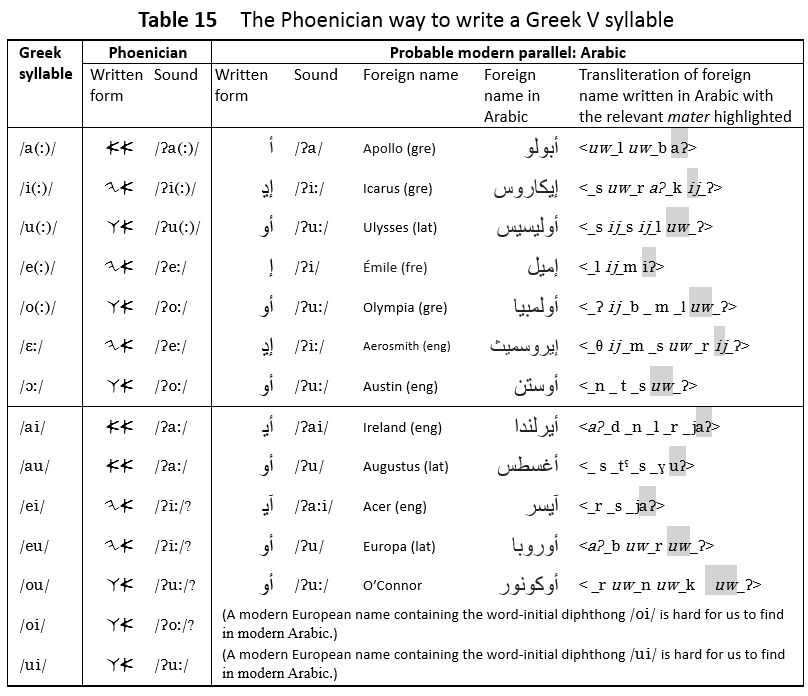

11.3 The Phoenician way to write a Greek V syllable

Judging from the spelling of ancient Greek names in the local scripts of archaic Greece, many of such names began with a V syllable. This word-initial syllable consisted of only one vowel, which was either a monophthong or a diphthong. The word-initial V syllables commonly used in ancient Greek names are: /a(:), i(:), u(:), e(:), o(:), ɛ:, ɔ:, ai, au, ui, ei, eu, oi, ou/. How would the Phoenicians write these syllables, when they did not have any words beginning with V syllables in their language? By examining the way in which foreign names with word-initial V syllables are represented in the modern Arabic script, one can hazard a guess at the possible ways in which the Phoenicians tackled the task.

As can be seen in Table 15 below, a word-initial V syllable in a foreign name is treated as a CV syllable comprising a glottal stop /Ɂ/ + a V in the Arabic script. This being the case, it is possible that under the influence of their mother tongue, the Phoenicians would hear a Greek V syllable as a CV syllable comprising a glottal stop /Ɂ/ + a V. For example, the Phoenicians would probably perceive the word-initial syllables /a/, /i/, and /u/ in Greek as sounds close to their /Ɂa/, /Ɂi/, and /Ɂu/ respectively, and so would write the Greek V syllables /a/, /i/, and /u/ as <aʔ _ʔ>, <ij _ʔ>, and <uw _ʔ> accordingly. The first sign of each of the above three written forms is <_ʔ>, which stands for the /Ɂ_/ syllables. The second sign is the mater that specifies the sound value of <_ʔ> /Ɂ_/. Table 15 below shows how the Phoenicians might write the Greek word-initial V syllables.

To write the Greek word-initial V syllables, the Phoenicians might use <aʔ _ʔ> /Ɂa(:)/ for /a(:), ai, au/, <ij _ʔ> /Ɂi(:)/ or /Ɂe:/ for /i(:), e(:), ɛ:, ei, eu/, and <uw _ʔ> /Ɂu(:)/ or /Ɂo:/ for /u(:), o(:), ɔ:, ou, oi, ui/.

It should be noted that the Arabic way of writing a foreign V syllable is a very much developed one. As can be seen from Table 15, the ordinary or normal sign that represents the word-initial /Ɂ_/ syllable in a foreign name seems to have been differentiated by the use of diacritics. The sign أ very often stands for /Ɂa/, but it may also stand for /Ɂu/ or /Ɂ_/. Its sound value is to be determined by the reader. The signs ﺇ and آ, however, are less ambiguous: they stand for /Ɂi/ and /Ɂa:/ respectively. The above signs can be followed by a mater. For example, ﺇﮃ and ﺃﻮ stand for /Ɂi:/ and /Ɂu:/ respectively. It can be said that when compared with the Arabic way of writing a V syllable in a foreign name, the Phoenician way of writing a Greek V syllable is perhaps generally more primitive or primary.

11.4 The Phoenician way to write a Greek VC syllable

How would the Phoenicians write the Greek VC syllables? The Phoenicians might turn the VC syllables into CVCV or CVC. The possible ways in which the Phoenicians wrote CVCV or CVC syllables have been explained above.

11.5 The Phoenician way to write a Greek consonant cluster

The Greek language has consonant clusters, which the Semitic languages generally lack. How would the Phoenicians write the consonant clusters in such a Greek name as /kle-o-pa-tra/? Some Phoenicians might turn a C1C2 cluster into a single C by leaving out the less prominent C. The syllable /kle/ might be written as <ij_k> /ki:/ or /ke:/, and the syllable /tra/ as <aʔ_t> /ta:/. Phoenicians who had sharp ears might write the first syllable /kle/ as <ij_l ij_k> /kili:/ or /kile:/ and the last syllable /tra/ as <aʔ_r aʔ_t> /tara:/, by turning each CCV syllable into two CV syllables. They might realize at a later stage that they could write the Greek sounds /kle/ and /tra/ more accurately by leaving out the first mater of each written form. They would read <ij_l _k> and <aʔ_r _t> as /kəli:/ (or /kəle:/) and /təra:/ respectively. When reading <ij_l _k> and <aʔ_r _t>, they would try to pronounce the schwa /ə/ as lightly as possible.

11.6 How the Phoenicians would write and read a Greek name

Based on their ways of writing various syllable structures in Greek names that have been discussed so far, the Phoenicians might write and read the following four Greek names as shown in Table 16.

The Phoenician ways to write and read Greek names would be conditioned by both their method of writing foreign names and their perception of Greek sounds. The closeness of the Phoenicians’ reading of a written Greek name to the actual Greek pronunciation should be of secondary importance as long as the Phoenicians could identify the person or place that the name stood for when reading out the written name.

[1] It should be noted that when the Greeks wrote in boustrophedon style, the signs would appear in reversed forms.

[2] See Allen (1974:54-55) as to why the Greeks might have chosen the signs σδ <sd> to represent /zd/ if /zd/ had existed at the time when the Greeks first adopted the Phoenician alphabet.

22 January 2017

Views: 814