We consider Section 12 to be the most important chapter of our treatise on the origin of the Greek alphabet, and we recommend that the readers read it carefully in order to understand how the concepts of vowel and consonant arose in the first quarter of the first millennium BC in ancient Greece.

12 From the Phoenician way of writing Greek names to the Greek way of writing the Greek language

12.1 From the writing of Greek names to proto-Greek alphabetic writing

As was said earlier, the Phoenicians might have needed to record Greek names in book-keeping in the second millennium BC. In theory they could write a Greek name either with or without matres. But in practice the Phoenicians would soon come to realize that a Greek name written with matres, being less ambiguous in sound representation, was much easier to read out or read back afterwards than one written without matres. Thus the Phoenicians would probably decide at an early stage to use matres to write Greek names. However, their way of writing Greek names might have escaped the notice of the Greeks at the earliest stage because the Greeks had not yet realized that it could be put to some significant use in their daily lives.

Towards the end of the second millennium BC, because of the intense contacts between the Phoenicians and the Greeks, some Greeks might come to realize that the Phoenicians only used about twenty signs to write Greek names in book-keeping. They would be amazed to find that any Greek names could easily be written by means of the Phoenician signs and that some Greek names, when read out by the Phoenicians, sounded pretty close to their own pronunciations. As regards Greek names, it should be noted that a Greek name might comprise everyday Greek words. For example, the Greek names Aristoteles and Cleopatra mean respectively ‘the best purpose’ and ‘glory of the father’. This being the case, some Greeks might sooner or later realize that by and large the Greek language could be written with only about twenty Phoenician signs in the same way as Greek names were written. This idea might have motivated the Greeks to learn writing, possibly in the tenth century BC, from the Phoenicians.

To use a foreign alphabet to write one’s native language, it is easier for one to learn from native users of that alphabet how they use their alphabet to write out the words of the language than for one to try to write the language on one’s own after learning the alphabet. Similarly, it would be easier for the Greeks to learn direct from the Phoenicians how to write the sounds of Greek in the Phoenician alphabet than for the Greeks to try to write Greek on their own after learning the Phoenician alphabet. Many people assume that the Greeks attempted to write their language on their own after learning the Phoenician alphabet. However, judging from the Phoenician signs that were adopted to write archaic Greek, it seems that the Greeks simply followed the Phoenicians’ lead in writing their own language at the earliest stage, as has just been explained in §11.

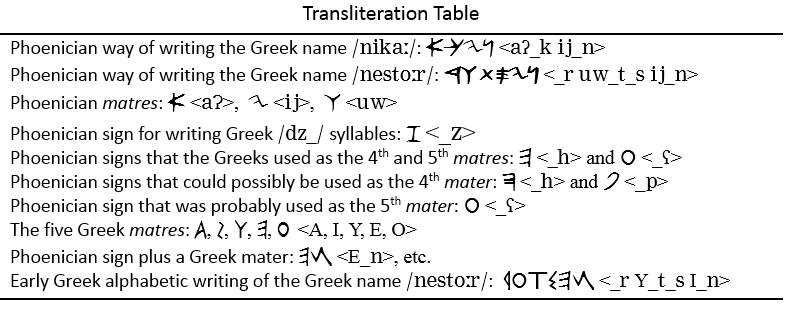

To learn to write Greek in Phoenician signs, some Greeks might ask a Phoenician how Greek names were written and why they were so written. The Phoenician might write out a Greek name, say, /nika:/ as <aʔ_k ij_n> and then explain how the signs functioned in the written name. We think that the Phoenician might explain in the following way.

The first sign <_n>, called nūn (or the like), stood for several sounds in Phoenician, which he would probably say aloud for the Greeks: /na(:)/, /ni(:)/, /nu(:)/, /ne:/, /no:/. All the Greek “sounds” that sounded like the above Phoenician sounds would be written as <_n>.

The second sign <ij>, called yōd (or the like), was a rhyme indicator (technically called a mater in this treatise) that required the preceding sign <_n> to rhyme with it. <ij>, read as /ji/ in its role as a rhyme indicator here, required <_n> to be read as /ni(:)/. Therefore, <ij_n> would be read as /ni(:)/.

The third and fourth signs <aʔ_k> functioned in the same way as the first and second signs <ij_n>. The third sign <_k> stood for /ka(:)/, /ki(:)/, /ku(:)/, /ke:/, and /ko:/, and the fourth sign <aʔ> required <_k> to rhyme with it. <aʔ>, read as /ʔa/, required <_k> to be read as /ka(:)/. Therefore, <aʔ_k> would be read as /ka(:)/. The whole name <aʔ_k ij_n> should be read as /nika:/.

The writing of the Greek name /nika:/ as <aʔ_k ij_n> involves the use of two principles. The first is the principle of the multiple sound values of a Phoenician sign; the second is the rhyming principle of a mater. These two principles should not be too difficult for the Greeks to understand. Once the Greeks understood why /nika:/ was written as <aʔ_k ij_n>, they had already learned the two most fundamental principles of proto-Greek alphabetic writing.

If the Greeks could further understand why the name /nesto:r/ could be written as <_r uw_t _s ij_n>, they would be able to grasp all the basic principles of proto-Greek alphabetic writing. Regarding the written form <_r uw_t _s ij_n> of the name /nesto:r/, the Phoenician might explain that the signs <ij_n> and <uw_t> would be read as /ni(:)/ and /tu(:)/ according to the rhyming principle. However, they could also be read as /ne:/ and /to:/. The sound /ne:/ in /nesto:r/ would be written as <ij_n>, but not as <aʔ_n> or <uw _n>, because among the sounds of <aʔ_n>, <ij_n> and <uw _n> (i.e. /na(:), ni(:), nu(:)/), the sound /ni(:)/ was the closest to /ne:/. By the same token, the sound /to:/ in /nesto:r/ would be written as <uw _t>. Thus <ij_n> could be read as /ni(:)/ and /ne:/, and <uw _t> as /tu(:)/ and /to:/. That <ij_n> and <uw _t> each had two basic readings could be regarded as an extension of the rhyming principle.

The signs <_s> and <_r> in the name <_r uw_t _s ij_n> are not followed by any matres. In this case, they should be read as /sə/ and /rə/. The strength of the schwa /ə/ could vary, but /sə/ and /rə/ should be spoken in such a way that they sounded like the original sounds of the name. This is the principle of the sound of a Phoenician sign not followed by a mater.

The Greeks, through the observation of a lot of Greek names written in Phoenician and through their attempts to write various Greek names in Phoenician signs, would gradually come to grasp how the Phoenician alphabet worked.

As regards the reading of the Greek names written in the Phoenician alphabet, it must be noted that the Greeks would not follow the Phoenicians’ way of reading their names, which was bound to be different from the native speakers’ pronunciations of the names to a greater or less extent owing to the difference between the Phoenician and Greek phonological systems and to the limitation of the Phoenician writing system in representing foreign sounds. A Greek name read in any way other than the Greek way of pronouncing it would sound foreign or unnatural to the Greek ear. Thus the Greeks would naturally read their names in their own native way. This, however, would bring about a new relationship between the Phoenician written forms and their corresponding Greek sound values. For example, while the Phoenicians would read the sign <_z> as /z_/, the Greeks would read it as /dz_/.

After grasping the basic principles of proto-Greek alphabetic writing, the Greeks would try to write Greek for some practical purposes such as book-keeping. They would find that the sound of a word was fairly accurately represented with only about twenty Phoenician signs. They might then try to write short messages and simple records of events with these signs. As the Greek words were written with matres, the three Phoenician matres would be used persistently and extensively, and an embryonic form of Greek alphabetic writing would emerge from this. We call this stage of Greek writing with three matres proto-Greek alphabetic writing. The idea that it was possible to use only about twenty signs to write the Greek language might have spread from one Greek region to another during the tenth century BC.

12.2 The inadequate number of matres in proto-Greek alphabetic writing

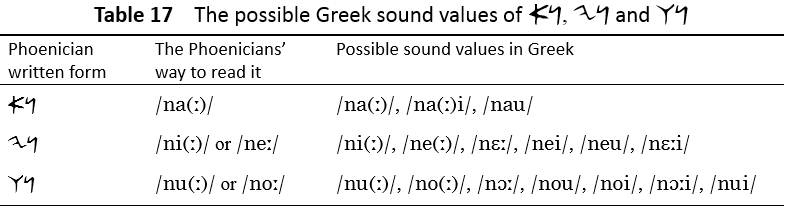

There is little doubt that proto-Greek alphabetic writing had various flaws, such as the use of two or three different signs to represent syllables with the same initial consonant (see Table 12.2) and the use of the same sign to represent syllables with two different initial consonants (see Table 12.3). But the flaw that troubled the Greeks most would be the inadequate number of matres in their writing. To the Phoenicians, a sign plus a mater, such as <aʔ_n>, <ij_n>, or <uw _n>, would have only one or two readings, but the Greeks would find that a sign plus a mater could stand for five to nine syllables, as can be shown in Table 17 below.

It can be seen from the table above that a Phoenician sign plus a mater represented a fairly large number of Greek syllables. If matres were not used to write the Greek language, a Phoenician sign could represent as many as twenty-two Greek syllables. Obviously, a name or word written with matres would be easier to read than one written without. The Greeks might have known that Phoenician was normally written without matres and might have attempted to follow suit. If they ever did so, they would soon realize that it would not be easy to read back what had been written and that it would be better to write with matres than to write without. From their experience of reading out written words, the Greeks would feel that it would be even better to write with more matres.

The Greek scholar E. Voutiras remarks that the ancient Greeks almost always read aloud (2007:275). The ancient Greeks had a habit of reading aloud probably because words in proto-Greek alphabetic writing were not always easy to identify. Word identification in proto-Greek alphabetic writing was difficult for two reasons. First, words were normally written together without any word spaces or dividers. Second, at the initial stage of proto-Greek alphabetic writing when all written words were new, it would take the Greeks a lot of time to familiarize themselves with the shapes of their written forms. One way to help identify the written words would be to read them out aloud to see which of the various possible readings would fit in with a particular context. It would be very natural for the Greeks to exploit their mother tongue to facilitate word identification. When reading a written word aloud, the ancient Greeks would treat a Phoenician sign plus a mater as a unit. The fewer sound values this unit had, the more easily they could work out its precise sound value. Since proto-Greek alphabetic writing had only three matres, the ancient Greeks would at times run into words that they could not easily identify. Despite their attempts to read out these words, they might not be able to get the right sounds of the words that would fit the context. They might wonder then whether the use of more matres, in addition to the three existing ones, would make the reading of such words easier.

It can be seen from Table 17 above that the use of three matres would not be sufficient to differentiate amongst /ni(:)/, /ne(:)/, and /nɛ:/, or amongst /nu(:)/, /no(:)/, and /nɔ:/, as <ij_n> represents /ni(:)/, /ne(:)/, and /nɛ:/, and <uw _n> /nu(:)/, /no(:)/, and /nɔ:/. The syllables ending in the mid vowels /e(:)/, /ɛ:/, /o(:)/ and /ɔ:/ were amongst the most frequently used Greek syllables in the spoken language, but there were no specific matres to represent them (see Appendix 9). To represent these syllables, the Greeks had to use the matres <ij> and <uw> that were originally used to represent the sounds ending in /i(:)/ and /u(:)/. For example, the Greeks could only write /ne(:)/ or /nɛ:/ as <ij_n>, which was originally the written form for /ni(:)/, and similarly they could only write /no(:)/ or /nɔ:/ as <uw _n>, which was originally the written form for /nu(:)/. The Greeks would probably think it better to find two more matres so that the frequently-used syllables that ended in /e(:)/ (or /ɛ:/) and /o(:)/ (or /ɔ:/) could have their specific mater to indicate their precise sound value.

The Greeks probably knew that the use of <ij_n> to represent /ni(:)/ was a true application of the rhyming principle, whereas the use of <ij_n> to represent /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/) was made possible only by an extension of this principle. They might wonder whether /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/) could be better represented by a new mater that rhymed precisely with it. The same can be said regarding the use of <uw _n> to represent /nu(:)/, /no(:)/, and /nɔ:/. The Greeks might also wonder whether the syllable /no(:)/ (or /nɔ:/) could be better represented by a precise mater. The mid vowels /e(:), ɛ:, o(:), ɔ:/ being amongst the most frequently used vowels in ancient Greek, the Greeks would instinctively feel that by creating two more matres for rhyming with syllables ending in the mid vowels, they should be able to read Greek more easily.

The Greeks would then search hard for two more matres which they felt were essential to a more faithful representation of their spoken language. Obviously, the sounds of these two new matres had to rhyme with /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/) and /no(:)/ (or /nɔ:/) respectively. Which two signs of the Phoenician alphabet could satisfy this requirement? How could these two Phoenician signs have the sounds that rhymed with /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/) and /no(:)/ (or /nɔ:/)?

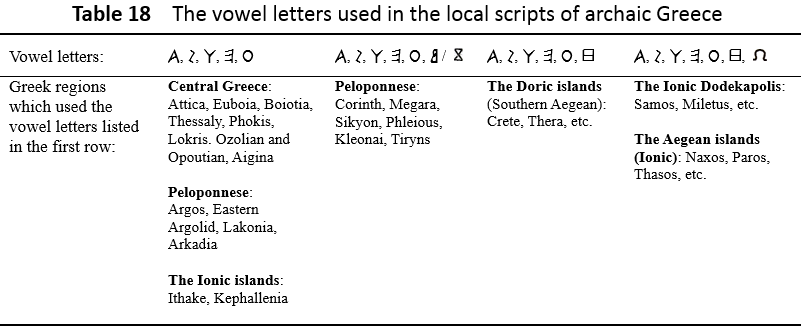

From the vowel letters that were used in archaic Greek inscriptions in the second quarter of the first millennium BC, one can infer that the Phoenician signs <_h> hē and <_ʕ> ʽayin were probably chosen as the fourth and fifth matres, possibly in the ninth century BC when the need to create two more matres was more and more keenly felt as the use of proto-Greek alphabetic writing expanded. Table 18 below shows the vowel letters that were used in the local scripts of archaic Greece.

About the vowel letters that were used in the local scripts of archaic Greece, we would like to make the following points:

- As far as the representation of vowels is concerned, the archaic Greek alphabets are structurally unified, although the letters of these alphabets may assume quite different shapes. All these alphabets have in common the following five basic vowel monographs: <Α, Ι, Υ, Ε, Ο> (or their variant letter shapes).

- The five basic vowel monographs used in archaic Greek inscriptions probably point to one single origin of the archaic Greek alphabets.

- We believe that <Α, Ι, Υ, Ε, Ο> had all been used as matres before they evolved into vowel letters. <Α, Ι, Υ> are traditional matres inherited from the Phoenicians; <E, O> are the fourth and fifth matres created by the Greeks. Why <E, O> were chosen as matres and how <Α, Ι, Υ, Ε, Ο> changed from matres into vowel letters will be explained in §12.3 and §12.5.

- The letter <ʙ> that was used in Corinth and Megara is possibly a variant form of <H> or <E>, and the letter <8> that was used in the neighbouring city Sykion is probably a variant form of the Corinthian <ʙ>. These two points will later be elaborated on.

- The vowel letter <H> was probably created, possibly in the eighth century BC, in a Greek region where /h/ had been lost. The name of the letter <H> was /ɛ:ta/ there, not /hɛ:ta/. When Greek alphabetic writing became segmental, a letter would come to represent the initial segment of its name. For example, the letter <A> came to represent the initial segment /a(:)/ of its name alpha, and the letter <B> the initial segment /b/ of its name bēta. Hence in regions where the letter <H> was called /ɛ:ta/, <H> could be used to represent the initial segment /ɛ:/ of its name.

- The vowel letter <Ω> was created, possibly in the eighth century BC, in order to denote /ɔ:/. Before the creation of <Ω>, the letter <O> was used to represent both /o(:)/ and /ɔ:/. After <Ω> had been created to represent /ɔ:/, <O> came to represent /o(:)/ The letter <Ω> was created probably by modifying the shape of the letter <O>.

12.3 The creation of two more matres in early Greek alphabetic writing

Why did the Greeks choose <_h> and <_ʕ> as matres? Some Greeks might have had the idea of using those Phoenician signs whose names could rhyme with /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/) and /no(:)/ (or /nɔ:/) as the new matres. The Greeks who thought in this way would be able to find only two Phoenician signs that could rhyme with /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/), namely <_h> hē and <_p> pē, but no sign that could rhyme with /no(:)/ (or /nɔ:/). They had to find another way to create a new mater for rhyming with /no(:)/ (or /nɔ:/).

One probable reason why the Greeks chose <_h> hē rather than <_p> pē as the mater for rhyming with /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/) was that <_h> hē could be used exclusively as a mater, but not <_p> pē. As was said in §11.1.1, it is possible that both <_h> hē and <_ḥ> ḥēth were used to represent the Greek /h_/ syllables. When <_ḥ> ḥēth was used to represent the Greek /h_/ syllables, <_h> hē could then be spared from having to represent /h_/ and thus be used exclusively as a mater for rhyming with /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/). The advantage of using a sign exclusively as a mater in archaic Greek alphabetic writing is obvious because the use of such a sign would facilitate ease of reading. As for <_p> pē, it could not be used exclusively as a mater for rhyming with /ne(:)/ (or /nɛ:/), because there was no substitute sign that could relieve it from having to represent the Greek /p_/ and /ph_/ syllables.

The idea of using <_h> hē as the mater for rhyming with syllables ending in /e(:)/ (or /ɛ:/) seems to have been well received in the Greek world. We believe that the Phoenician sign <_h>, read as /e:/ or /ɛ:/ in some Greek regions and as /he:/ or /hɛ:/ in others owing to dialect variation, was used at the early stage of Greek alphabetic writing as a mater. <_h_n >, for example, would probably be read as /ne(:)/ or /nɛ:/, because the mater <_h> /(h)e:/ (or /(h)ɛ:/) required <_n > /n_/ to rhyme with it.

In regions where /h_/ syllables were not spoken, <_h>, read as /e:/ or /ɛ:/, could undoubtedly be used exclusively as a mater since <_h> would not be required to write the /h_/ syllables. Even in regions where /h_/ syllables were spoken, <_h> could still be used exclusively as a mater if a substitute sign for writing /h_/ syllables could be found. Presumably, the Greeks could also use the Phoenician <_ḥ> ḥēth to represent /h_/ syllables (see §11.1.1). We believe that in early Greek alphabetic writing, <_h> was used exclusively as a mater, while <_ḥ> was used exclusively as a letter for writing the /h_/ syllables.

As can be seen from the local scripts of archaic Greece with five vowel letters, the letter <_ʕ> was used to represent the vowels /o(:)/ or /ɔ:/. As has just been said, there was no Phoenician sign whose name could rhyme with /no(:)/ or /nɔ:/. The Greeks would not be able to find a suitable mater to rhyme with /no(:)/ or /nɔ:/ in the same way as they would find the mater <_h> to rhyme with /ne(:)/ or /nɛ:/. The Phoenicians could not have used the sign <_ʕ> ʽayin to write any Greek syllables because no Greek syllables would begin with a sound close to the Phoenician pharyngeal fricative /ʕ/. How could the Greeks use this redundant sign as a mater to rhyme with /no(:)/ or /nɔ:/?

The Phoenicians would probably pronounce the name of the sign <_ʕ> as /ʕajin/ or the like, but the Greeks, having no such sound as /ʕ/ in their phonological system, would probably pronounce it as either /haiin/ or /aiin/. Neither the full name (/(h)aiin/) nor its initial syllable (/(h)ai/) seems to be able to rhyme easily with syllables ending in /o(:)/ or /ɔ:/. How could the Phoenician sign <_ʕ> be used as the new rhyming mater?

C. Brixhe, a French expert on ancient Greek, suggests that the Greeks probably found the sign <_ʕ> for the vowel /o/ in this way. The name of the Phoenician sign <_ʕ> /ʕajin/ means ‘eye’ in Phoenician. Probably because the sign looked like an eye, the Greeks called it the eye sign. As it so happened that all the words for ‘eye’ in ancient Greek began with /o/, the name of the eye sign would begin with /o/ whichever Greek word was chosen. By applying the acrophonic principle, the Greeks could then use the sign <_ʕ> to represent the initial sound of its name: /o/ (2007:285). Brixhe’s idea seems to be supported by such ancient Greek words as οϕθαλμος /ophthalmos/ ‘eye’, ομμα /omma/ ‘eye’, οφις /opsis/ ‘sight’, οσσε /osse/ ‘two eyes’, which all begin with the sound /o/.

Brixhe’s suggestion about the provenance of the vowel letter <_ʕ> is plausible. However, while Brixhe’s concern is with how the Phoenician sign <_ʕ> could become a vowel letter, our concern here is how it could become a mater. In searching for a mater for rhyming with syllables ending in /o(:)/ or /ɔ:/, some Greek or Greeks might have hit upon the idea of exploiting the initial CV or V syllable of the Greek name of a sign rather than its original Phoenician name. In this case the Greeks should be able to isolate the initial V syllable /o/ of the Greek name of the eye sign and use it to rhyme with syllables ending in /o(:)/. The eye sign <_ʕ>, read as /o/ as a mater, could then require the preceding sign to rhyme with it. This idea would catch on in the Greek world as it met the need for a much required mater that could rhyme with syllables ending in /o(:)/.

It seems rather easy for the Greeks to have found two more matres. But it should be noted that the original three matres evolved naturally from ancient Egyptian writing, whereas the Greeks’ search for two more matres represents a deliberate effort to create them. The Greeks must have fully grasped the rhyming principle of the matres before they could create them by exploiting either the name of a sign or the initial CV or V syllable of its name.

12.4 Early Greek alphabetic writing with five matres

Nobody knows exactly when the Greeks created two more matres. But from the inscription on the Dipylon vase we know that these two matres had already been created by 740 BC. As was said earlier, the Greeks might have been motivated to learn writing with three matres from the Phoenicians as early as the tenth century BC. It would probably take the Greeks a long time to develop two more matres for common use in their writing to reach the stage at which they had five matres at their disposal: <Α, Ι, Υ, Ε, Ο>. We believe that these five Greek matres <Α, Ι, Υ, Ε, Ο> originated respectively from the three Phoenician matres (<aʔ>, <ij>, <uw>) and the two ordinary Phoenician signs (<_h> & <_ʕ>).

At the earliest stage of proto-Greek alphabetic writing, the percentage of literate Greeks should be very low, and the areas to which writing could be applied very limited. The development of proto-Greek alphabetic writing would be slow, only to pick up pace at a later date when the literacy rate went up and the areas of the application of writing widened. Therefore it might have taken a century for proto-Greek alphabetic writing with three matres to evolve into early Greek alphabetic writing with five matres. The Greeks might have found two more matres in the ninth century BC.

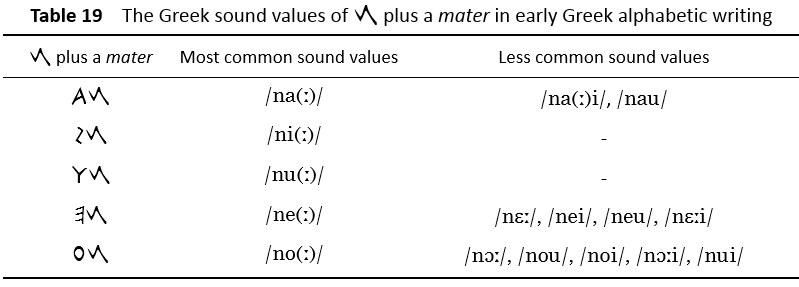

We call the stage of Greek writing with five matres the beginning of early Greek alphabetic writing, as distinct from proto-Greek alphabetic writing with three matres. With five matres, the Greeks would be able to write and read Greek syllables more accurately than before. A sign plus a mater would basically represent one definite Greek syllable comprising a consonant plus a monophthong, as the diphthongs occurred much less frequently than the monophthongs in ancient Greek (see Appendix 9). This can be seen in Table 19 below, which shows the most common and the less common Greek sound values of <_n> plus a mater in those Greek regions where five matres were in use.

It should be noted that in regions where the monophthongs /ɛ:/ and /ɔ:/ existed, <Ε_n> also represented /nɛ:/ apart from /ne(:)/, and <O_n> also represented /nɔ:/ apart from /no(:)/. Even so, <Ε_n> and <O_n> probably represented /ne(:)/ and /no(:)/ much more often than /nɛ:/ and /nɔ:/ (see Appendix 9). Thus the statement that a sign plus a mater in early Greek alphabetic writing basically represented one definite Greek syllable is generally true for all Greek regions where five matres were used. Since a sign plus a mater in early Greek alphabetic writing basically represented one definite Greek syllable, and since three or even four of the five rhyming matres were read as V syllables, early Greek alphabetic writing was in a good position to evolve into a segmental writing system.

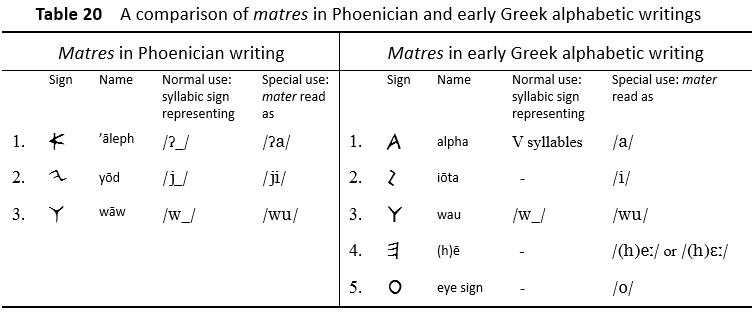

How would the Greeks read the five matres <Α, Ι, Υ, Ε, Ο>? As can be seen from Table 20 below, in Phoenician the signs <_ʔ>, <_j>, and <_w> would be read respectively as /ʔa/, /ji/, and /wu/ when used as matres. When borrowed by the Greeks for use as matres, they would be read, however, as /a/, /i/, and possibly /wu/. The mater <aʔ> would be read as /a/, because the glottal stop /ʔ/ did not exist in Greek. When the Greeks heard the Phoenician sound /ʔa/, they would tend to miss the initial glottal stop /ʔ/ under the influence of their phonological system. The mater <ij> would be read as /i/, not /ji/, because it is generally believed that the consonant /j/ had been lost early in ancient Greek. It is assumed that the letter <I> that appears before another vowel letter in the local scripts of archaic Greece represents the vowel /i(:)/, not the consonant /j/. While the Phoenicians probably read the name of the sign <_j> as /jo:d/, the Greeks probably read it as /i ɔ: ta/ in conformity with their phonological system. As regards the relationship between the consonant /j/ and the vowel /i/, it should be noted that /j/, when lengthened slightly, easily becomes a vocalic /i/ and that /i/, when shortened slightly, easily becomes a consonantal /j/. As for the mater <Y>, it would probably be read as /wu/ in regions where /w/ could be used as a consonant before a vowel. The sound /wu/ might have evolved into /u/ or /hu/ in regions where /w/ had disappeared before a vowel. It should be noted, however, that /u/, used as a word-initial syllable, is not attested in those archaic Greek inscriptions that are published in Jeffery’s The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece. We assume therefore that <Y> might be read as /hu/ when used as a mater in regions where /w/ had disappeared. How the Greeks would read their new-found Greek matres <E> and <O> has been dealt with in §12.3. The Greeks would probably read the mater <E> as /(h)e:/ or /(h)ɛ:/, and the mater <O> as /o/.

As has just been explained, of the five Greek matres, <A, I, O> were most probably read as V syllables (/a/, /i/, and /o/) in Greek. <E> was also read as a V syllable (/e:/ or /ɛ:/) in many Greek regions. When three or four out of five matres were read as V syllables, they would tend to transform themselves from matres into vowel letters in early Greek alphabetic writing (this point will be dealt with later on). When <A, I, E, O> were on their way to becoming vowel letters, the remaining mater <Y> would tend to change into a vowel letter in an analogous manner, and its reading would thus change from /wu/ into /u/.

The five Phoenician signs <_ʔ, _j, _w, _h, _ʕ> evolved into <A, I, Y, E, O> in early Greek alphabetic writing. It should be noted that of the five Greek signs, <I, Y, E, O> would be used exclusively as matres. In Phoenician writing, no matter whether <_ʔ, _j, _w> were used as ordinary letters or as matres, their shapes remained unchanged. The Greeks, however, wanted to differentiate the shape of an ordinary letter from that of a mater in order to facilitate ease of reading. From their experience of using matres, the Greek would come to realize that when a sign was used exclusively as a mater, it could be identified easily. Once it was identified, its function as a mater would become clear and distinct, and this would make reading easier.

It is quite obvious that <I> and <O> would be used only as matres, but not as ordinary letters. As there were no such syllables as /j_/ and /ʕ_/ in ancient Greek, <I> and <O> were not required to denote these sounds and so could be used exclusively as matres. As regards the letter <Y>, it was probably used as both an ordinary sign and a mater initially. Later, while its variant form <F> was used as an ordinary sign standing for /w_/, <Y> was probably used exclusively as a mater, which was read possibly as /wu/. The use of <E> exclusively as a mater has been discussed at some length earlier in this treatise. It is possible that in early Greek alphabetic writing <E> was used exclusively as a mater while <_H> was used as an ordinary letter for writing the /h_/ syllables.

The case of <A>, however, is more complicated. As explained in §11.3, the Phoenicians might use <aʔ_ʔ>, <ij_ʔ>, and <uw_ʔ> to write the Greek syllables /a/, /i/, and /u/. When the Phoenicians explained to the Greeks that the first sign <_ʔ> should be read as /ʔa/, /ʔi/, /ʔu/, etc, and that the second sign was a mater that determined its sound values, the Greeks would tend to miss the Phoenician glottal stop /ʔ/ under the influence of their mother tongue and would hear /ʔa/, /ʔi/, /ʔu/ as /a/, /i/, /u/. The Greeks would come to understand that the sign <_ʔ> could be used as either an ordinary letter or a mater. When used as an ordinary letter, it should be read as /a/, /i/, /u/, etc; when used as a mater, it would indicate that the preceding sign should be read as a syllable ending in /a(:)/.

Proto-Greek alphabetic writing would evolve into early Greek alphabetic writing when two more matres were created. When five matres were ready for use to write everyday words, Greek writing, presumably, had come of age.

12.5 How the Greek signs changed into vowel and consonant letters

Over time, the five matres <A, I, Y, E, O> would evolve into vowel letters. The earliest extant Greek inscription on the Dipylon vase is already a mature piece of segmental writing. The five signs <A, I, Y, E, O> used in the inscription, we believe, are vowel letters, no longer matres.

We believe that a mater plays an indispensable role in proto-Greek and early Greek alphabetic writings. While the Phoenicians used matres sparingly in Phoenician writing, the Greeks would use matres to write Greek as a rule. A sign plus a mater would be a basic unit of writing in Greek. The reading of a sign in Phoenician writing was context-dependent, whereas that of a sign plus a mater in Greek writing would become more definite when the number of matres had increased from three to five. When there were only three matres, a sign plus a mater could stand for five to nine syllables (see Table 17). When five matres were in use, a sign plus a mater basically stood for one single syllable (see Table 19). For example, <I_n> and <Y_n> would be read definitely as /ni(:)/ and /nu(:)/ respectively; <A_n>, <E_n>, and <O_n> would be read quite often as /na(:)/, /ne(:)/, and /no(:)/ respectively. This is a major departure from Phoenician writing, in which an ordinary sign, written generally without a mater, stood for several syllables.

That a sign plus a mater basically stood for only one syllable would enable the Greeks to see clearly the relationship between the written form and its pronunciation, which would ultimately lead to the perception of a mater as a vowel letter. The five matres must have gone through a long period of gestation before they changed into vowel letters. The evolution of the matres into vowel letters can roughly be divided in four stages as described in the following paragraphs and as schematically presented in Table 21 below. When reading the following description of the evolution of the matres, one may refer to the relevant stages in Table 21.

The written form <I_n> is used as an example to illustrate how a mater would gradually be perceived as a vowel letter by the Greeks. We will attempt to see the change of the mater’s role from the Greeks’ perspective when they still had no phonemic concept. Since Greek alphabetic writing was read mainly from right to left before the sixth century BC, the written form <I_n> (written as <ij_n> in proto-Greek alphabetic writing) is to be read from right to left too. When written boustrophedon, <I_n> became <n_I>. <n_I> should then be read from left to right.

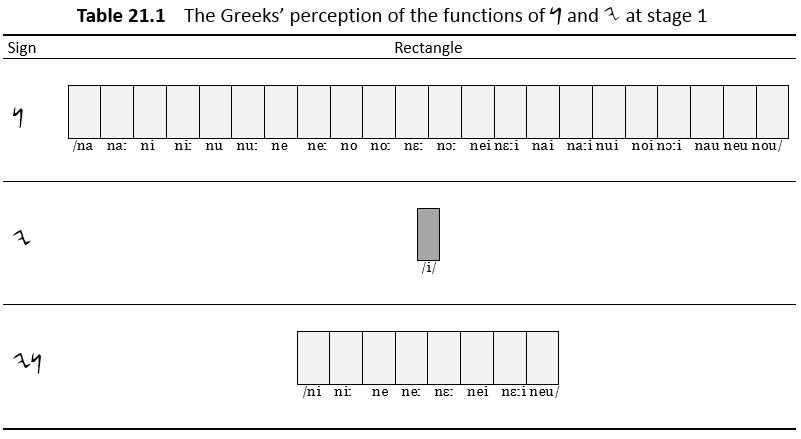

At stage 1, when there were only three matres, <_n>, still in its Phoenician form, could have as many as twenty-two “sounds”. Each sound was the smallest speech sound unit, which one calls a syllable today. The mater <I> would reduce the twenty-two sounds of <_n> to eight, which can be transcribed today as /ni(:)/, /ne(:)/, /nɛ:/, /nei/, /nɛ:i/, /neu / (see Table 17 above and Table 21.1 below). Any one sound of <_n> would be regarded by the Greeks as an integral whole sound unit and is represented here by a light grey rectangle in Table 21.1. The sound of the Greek mater <I>, transcribed today as /i/, is represented by a dark grey rectangle. Since <I_n> had eight sounds, the mater <I> would serve as a rough phonetic indicator only. In a piece of writing, the context would further determine which sound of <I_n> should be used.

As can be seen from Table 21.1 below, even though <I_n> could stand for /ni(:)/, the Greeks were unlikely to regard <I> as representing the last part of the /ni(:)/ sound, because <I_n> could also stand for /ne(:)/, /nɛ:/, /nei/, /nɛ:i/, /neu / apart from /ni(:)/. Besides, it stood more often for /ne(:)/ than for /ni(:)/ (see Appendix 9).

At the outset of stage 1, the pace of development of proto-Greek alphabetic writing must have been very slow as the Phoenicians only needed to write Greek names sporadically. It would also take the Greeks a considerable period of time to learn the Phoenician method of writing Greek sounds and to put it to practical use. The insufficiency of this method would be more and more keenly felt by the Greeks when Greek alphabetic writing was put to wider use. It would also take the Greeks a long time to find two more matres to write Greek more accurately. Stage 1 should span a very long period of time.

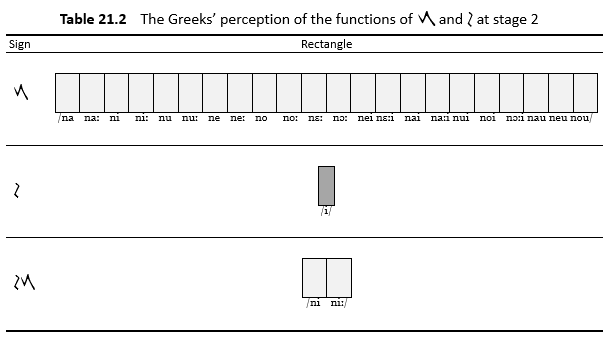

At stage 2 (see Table 21.2 below), there would be five matres. We assume that at this stage the shape of the Phoenician letters, including the matres, had evolved into a simpler form. Table 19 above shows the ordinary letter <_n> and the five matres in simpler form. <_n> would still have as many sounds as before. However, the mater <I> would reduce the number of <_n>’s sounds from twenty-two to only two, transcribed today as /ni/ and /ni:/ (see Table 19 above). Thus <I_n> would basically have only one sound value: /ni/. That <I_n> had only one sound value would be critical in the development of Greek alphabetic writing: a sign plus a mater would basically represent a definite sound. When coming across the signs <I_n>, the Greeks would not have to think about what other sounds <I_n> might represent apart from /ni/. That is, they could rule out at once the possibilities that <I_n> might also be read as /ne(:)/, /nɛ:/, etc. It would eventually dawn on them that <I_n> was to be read unambiguously as /ni/ and only as /ni/. That <I_n> had only one sound value is a major departure from Phoenician writing, in which a sign had a set of sound values.

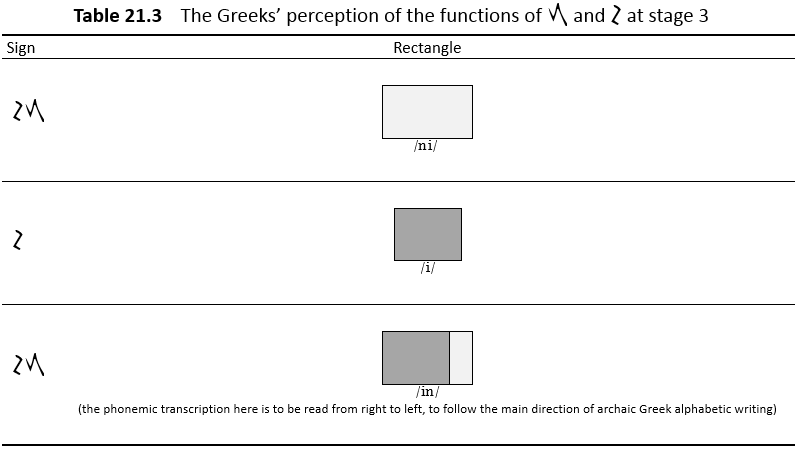

Stage 3 is the most crucial stage in the evolution of Greek alphabetic writing. It witnesses the transitional period during which Greek alphabetic writing evolved from a syllabic writing system into a segmental one, and it will be dealt with at greater length here. At the beginning of this stage, when coming across the simpler form of <I_n>, the Greeks would read it automatically as /ni/. To the Greeks, /ni/ was an integral sound unit, which they would not bother to analyse. However, from their aural and visual experience of reading and writing <I_n> and other written forms ending in <I>, the Greeks would sooner or later come to realize that not only could the sound of the mater <I> rhyme with the sound of <I_n> but it was also virtually the same as the rear part of <I_n>’s sound. With respect to sound quality, sonority, and duration, the rear part of <I_n>’s sound can be said to be nearly the same as the sound of the mater <I>. Thus it would not be very difficult for the Greeks to identify the rear part of <I_n>’s sound with the sound of the mater. This being the case, the Greeks might then wonder whether the mater <I> could be regarded as representing the rear part of <I_n>’s sound (see Table 21.3 below).

Traditionally, the Greeks would regard the mater <I> in <I_n> as a sound indicator of <_n> only. While <_n> by itself could have quite a lot of sounds, <I>’s function was to point out which ones of the sounds that <_n> should have. <I> would not be regarded as a sign that could represent a part of one of <_n>’s sounds. However, when <I_n> basically had only one sound and when the sound of <I> happened to be nearly the same as the rear part of this sound, it was then possible for the Greeks to perceive <I> as a sign that could represent the rear part of <I_n>’s sound.

The visual form <I_n> would also make it easier for the Greeks to perceive the sound of <I_n> as comprising two parts—the front and the rear. As the second sign <I> would gradually come to be perceived by the Greeks as representing the rear part of the sound, the Greeks might begin to wonder whether the first sign <_n> could be regarded as representing the front part of the sound.

The Greeks’ perception of the function of the matres would begin to change as a result of their experience of reading and writing those written forms ending in <I> such as <I_n> /ni(:)/, <I_b> /bi(:)/, <I_g> /gi(:)/, <I_d> /di(:)/, etc. Each of these written forms comprises two signs. The second sign <I>, common to each of these forms, would come to be perceived as representing the rear part of the sound of each written form, as has just been explained. This change in the Greeks’ perception of the function of the mater <I> would make the Greeks wonder whether the function of the other matres <A, Y, E, O> could be perceived in the same way.

As can be seen from Table 19, <A_n> and <O_n> would be read quite often as /na(:)/ and /no(:)/. When they were read in this way, the Greeks, aided by their perception of the mater <I> as representing the rear part of a sound, might also come to regard the matres <A> and <O> (read as /a/ and /o/) as representing the rear parts of /na(:)/ and /no(:)/. This way of perceiving the function of the matres <A> and <O> in <A_n> and <O_n> would be reinforced by the Greeks’ experience of reading and writing those written forms ending in <A> and in <O>, such as <A_b>, <A_g>, <A_d>, <O_b>, <O_g>, <O_d>, etc.

It can also be seen from Table 19 that <E_n> would be read quite often as /ne(:)/ and <Y_n> definitely as /nu(:)/. Just as the matres < I, A, O> could be regarded as representing the rear parts of /ni(:)/, /na(:)/ and /no(:)/ respectively, so the matres <E, Y>, by analogy, could be regarded as representing the rear parts of /ne(:)/ and /nu(:)/ respectively, even though the matres <E, Y> were not read as V syllables in many Greek regions.

From their experience of reading and writing <A_n, I_n, Y_n, E_n, O_n>, the Greeks would be more and more sure that the matres <A, I, Y, E, O> could be regarded as representing the rear parts of the sounds /na(:)/, /ni(:)/, /nu(:)/, /ne(:)/, and /no(:)/. This way of perceiving the function of the matres would be reinforced by the Greeks’ experience of reading and writing other written forms ending in a mater. Consequently, the five matres <A, I, Y, E, O> would eventually be regarded by the Greeks as representing a part of a syllable. This seems to be a small step taken by the Greeks in the development of their alphabetic writing. However, by taking this small step, the Greeks had in fact taken a giant leap for mankind. Not until the Greeks had taken this step did man realize that a sign could be used to represent a segment of a syllable.

The Greeks could regard a mater as representing a part of a syllable because Greek alphabetic writing had evolved into a stage at which the following two conditions were met: (1) two successive signs were used to represent basically a single CV syllable; (2) the second sign was read as a V syllable, which happened to rhyme with the sound represented by the two successive signs. These two conditions do not seem to be very unusual to people used to segmental writing, but it had taken more than two thousand years for these two conditions to arise naturally as a result of the script development from ancient Egyptian writing, through proto-Semitic, proto-Canaanite and Phoenician alphabetic writings, to early Greek alphabetic writing with five matres. Had any one of the above writing systems not been created, the above two conditions would not have occurred. It should be noted that before the advent of early Greek alphabetic writing, a mater had always been perceived as an indicator of a whole sound, but not as a sign that could represent a component part of a whole sound.

In early Greek alphabetic writing with five matres, the above-mentioned two conditions had arisen and so the Greeks would gradually come to realize that a mater could be regarded as representing the rear part of a sound. If a mater was thus regarded, then the question that inevitably followed would be: could the ordinary sign preceding the mater be regarded as representing the front part of the sound? For example, in the case of <I_n>, if the mater <I> was regarded as representing the rear part of the sound of <I_n>, could the ordinary sign <_n> be regarded as representing its front part? It must be noted that the Greeks had probably never imagined that <_n> could be regarded as representing only a part of a sound because they had been used to perceiving <_n> as representing quite a lot of sounds. Before they thought it possible to regard <I> as representing the rear part of the sound of <I_n>, they might even never have thought that the sound of <I_n> could have a front part.

Without the assistance of the visual form <I_n>, it might not have occurred to the Greeks that the sound of <I_n> could have two parts—the front and the rear. If the sounds of <I_n> and <I> had been written in Japanese kana as に and い, which have the sound values of /ni/ and /i/ respectively, they would probably have regarded the sounds of に and い simply as two different sounds, though with the same rhyme. The written forms of the two Japanese syllabograms would not have given the Greeks any visual clues that enabled them to come to the idea that a syllable could be made up of two parts. If they had regarded the sounds of <I_n> and <I> simply as two different sounds, they would not have bothered to give further thought to the relationship between them. It was probably the written form of <I_n> that forced the Greeks to recognize that the sound of <I_n> could have a front part. As the sign <I> was perceived as representing the rear part of the sound of <I_n>, the Greeks would be forced to consider whether <_n> could be perceived as representing its front part.

The Greeks would not be sure at first what sort of sound the sign <_n> could represent if the mater <I> was regarded as representing the rear part of the sound of <I_n>. To find out what sort of sound it was, they would be obliged to analyse the sound of <I_n>, probably by comparing it with the sound of <I>. They might reason that if <I> was regarded as representing the rear part of the sound of <I_n>, then <_n> could be regarded as representing the remaining part of the sound, that is, the front part. As this front part of the sound could hardly exist on its own in their language, the Greeks would probably have some difficulty in isolating it from the whole sound. In order to see what sort of sound the front part really was, the Greeks might do the following.

They might read out <I_n> as [ni] and the mater <I> as [i] to see how the sounds were different. They would find that the two sounds were articulated differently at the beginning, though ending in the same rhyme. They might then try out other sounds whose onset was the same as that of [ni], but whose rhymes were different, such as [na], [nu], [ne], [no]. To this end, they might read out <A_n>, <I_n>, <Y_n>, <E_n>, <O_n> as [na], [ni], [nu], [ne], [no]. In saying out these sounds, they would feel the presence of a common front part in each sound. In order to find out the phonetic nature of the front part, which was very short in duration, they might try to prolong this part deliberately by pronouncing, say, [na] as [nnna] to make it aurally more distinct. The Greeks would probably learn from this experiment that it was possible to regard <_n> as representing the front part of the sound.

They might also try out other sounds with the same rhyme as [ni], but different onsets, for example, by reading out <I_s>, <I_m>, <I_l>, <I_b>, <I_k> as [si], [mi], [li], [bi], [ki]. When saying out these sounds, they would unmistakably feel the presence of a different front part in each sound. In order to further explore the nature of the front parts of these sounds, they might try to prolong the front parts by pronouncing these sounds as [sssi], [mmmi], [llli], […bi], […ki] (the sign … here denotes the holding up of a sound before its release). They would feel from the sounds they said out that their front parts were articulated in different ways and that some of these front parts could be prolonged more easily than others. They could also hear from the sounds they said out that all these front parts were aurally different and that each front part had its own phonetic distinctiveness. The Greeks would probably learn from this experiment that the sign preceding the mater could decidedly be regarded as representing the front part of the sound.

As was said in §11.2, the Phoenicians might have used Sign1 + Mater1 + Sign2 to write a Greek CVC syllable. If this was the case, when recording such a Greek name as /nesto:r/, the Phoenicians would probably write it as <_r uw_t _s ij_n>, which would evolve, as was explained at great length in this treatise, into <_r Y_t _s I_n> in early Greek alphabetic writing. When coming across such a written name, the Greeks would read it as /nesto:r/. As a syllable-final consonant /s/ is easier to prolong than a syllable-initial consonant /s/, the Greeks would be able to pronounce [nesss] more easily than, say, [ssse]. When the consonant /s/ was pronounced [sss] as in [nesss], it could be isolated more easily from the whole sound /nes/. Consequently, the Greeks would be able to better grasp the phonetic nature of the syllable-final consonant /s/ that was represented by the sign <_s> in the written name <_r Y_t_s I_n>. The Greeks could then identify the less isolable syllable-initial consonant /s/ with the more isolable syllable-final consonant /s/, since the syllable-initial /s/ was phonetically similar to the syllable-final consonant /s/ in many ways. Just as the sign <_s> in the name <_r Y_t _s I_n> was used to represent the more isolable syllable-final consonant /s/, so the same sign <_s>, as was used in the written form, say, <I_s>, could be regarded as representing the less isolable syllable-initial consonant /s/, that is, the front part of the syllable /si/. What is said about the sign <_s> in <_r Y_t _s I_n> applies to the sign <_r> in <_r Y_t _s I_n>. The point to make in this paragraph is that the Greeks’ perception of the signs <_s> and <_r> in, say, <I_s> and <I_r>, as representing the front part of a syllable would be reinforced by their perception of the signs <_s> and <_r> in <_r Y_t _s I_n> as representing the more isolable syllable-final consonants /s/ and /r/.

To recapitulate, the way in which a CV syllable was written in early Greek alphabetic writing would also make it easier for the Greeks to perceive that a sound was made up of two parts—the front and the rear. For example, that /na/, /ni/, /nu/, /ne/, /no/ were written as <A_n>, <I_n>, <Y_n>, <E_n>, <O_n>—the same sign (<_n>) for the front parts but different signs (<A, I, Y, E, O>) for the rear parts—would make it easier for the Greeks to perceive that the front parts of the sounds were the same while the rear parts were all different. On the other hand, that /si/, /mi/, /li/, /bi/ were written as <I_s>, <I_m>, <I_l>, <I_b>—the same sign (<I>) for the rear parts but different signs (<_s>, <_m>, <_l>, <_b>) for the front parts—would make it easier for the Greeks to perceive that the front parts of the sounds were all different while the rear parts were the same. In other words, the visual representation of a CV syllable in early Greek alphabetic writing probably also played an important role in the Greeks’ perception of its component parts.

The Greeks would gradually come to have the idea that a sound could be regarded as being composed of two parts. For example, in the case of <I_n>, the ordinary sign <_n> and the mater <I> would eventually be regarded as representing the front and the rear parts of the sound /ni/ respectively. Thus the sound of <I_n> in the last row of Table 21.3 is represented by a rectangle comprising two parts that are different shades of grey—the light grey front part and the dark grey rear part. The rear part is dark grey because the Greeks identified the rear part of the sound of <I_n> with the sound of the mater <I>, which is represented by a dark grey rectangle in the row just above.

Traditionally, the Greeks had been used to regarding <I> as an indicator of the sounds of <_n>. Now that they perceived the functions of <I> and <_n> in a new way, the nature of Greek alphabetic writing was beginning to change, even though the written form <I_n> for the sound /ni/ remained unchanged. It would probably take the Greeks some considerable time to come to the conclusion that an ordinary sign plus a mater could be regarded as representing the front and the rear parts of a sound.

The longer the Greeks used their alphabetic writing with five matres, the more they would be convinced that the matres <A, I, Y, E, O> in, say, <A_n>, <I_n>, <Y_n>, <E_n>, and <O_n> could be regarded as representing the rear parts of the sounds /na(:)/, /ni(:)/, /nu(:)/, /ne(:)/, and /no(:)/ and that the ordinary sign <_n> could be seen as representing the front part of each of these sounds. The more experience the Greeks had in reading and writing <_n>, the better they would be able to grasp the transformed nature of <_n> and its new relationship with the sound it stood for. What had originally been thought to be an integral sound, say, /ni/ as represented by <I_n>, was eventually split up by the Greeks into two successive discrete parts or segments—/n/ and /i/, which later came to be called a consonant and a vowel. The Greeks had been used to perceiving <_n> in <I_n> as representing a lot of sounds, each one of which could be easily pronounced; now they used it to represent a part of a sound which could hardly exist on its own in their language. The nature of the sign <_n> had undergone a drastic change.

It must be noted that it would not be easy for people to perceive a consonant as a component part of a spoken sound without the visual aid of its written representation in segmental writing. This point is easy to understand, but tends to be overlooked by many people. Having learnt their alphabet since early childhood, these people take segmental writing so much for granted that they tend to think that such a syllable as /na/ can naturally be analysed into /n/ and /a/. It might not have occurred to them that this kind of analysis is by no means as natural as they think. As a matter of fact, until Greek segmental writing came into being in the first quarter of the first millennium BC, man was not able to isolate even the V element from a simple CV syllable, not to say the C element. There had been neither vowel letters nor consonant letters before the birth of Greek segmental writing. People who regard the Semitic alphabetic scripts as examples of consonantal writing might argue that in a consonantal writing system like Phoenician, from which Greek segmental writing evolved, a sign denotes a consonant. We have argued at great length in this treatise that in a so-called consonantal writing system like Phoenician, a sign stands for a set of CV syllables with a common onset followed by variable rhymes, not for a consonant.

We believe that to discover the use of a sign to stand for a consonant is no ordinary achievement. That the ancient Greeks were able to discover the use of such a sign was due to the occurrence of the following two conditions in early Greek alphabetic writing: (1) two successive signs represent a single CV syllable: (2) the second sign, read as a V syllable, rhymes with the CV syllable. As was said earlier in this section, the occurrence of these two conditions was contingent upon a combination of many factors. Had any one of these factors been missing, the above two conditions in the Greek alphabetic script would not have arisen.

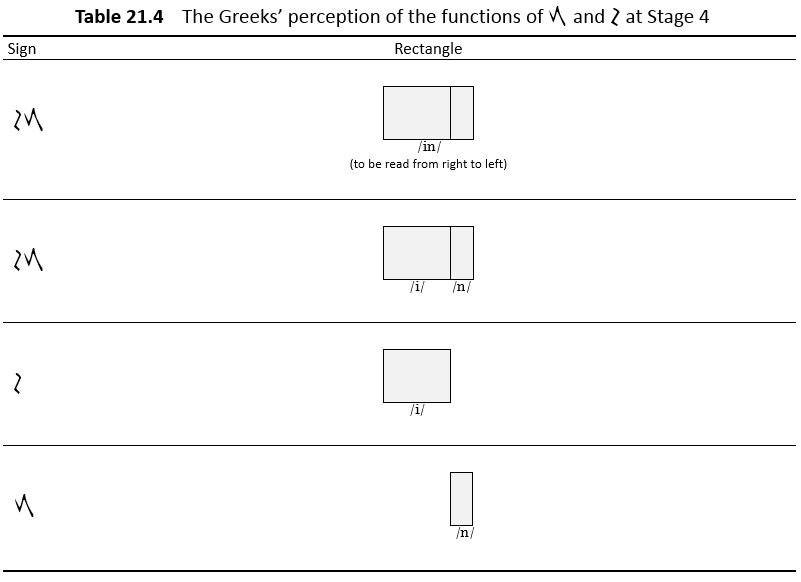

At stage 4 (see Table 21.4 below), the Greeks would eventually realize that in the written form of <I_n>, <_n> and <I> could be regarded as representing the front and the rear parts of <I_n>’s sound. When <_n> and <I> were regarded in this way, they were on their way to becoming a consonant letter and a vowel letter respectively. The ordinary sign <_n>, instead of denoting a lot of Greek syllables with a common onset, was regarded as representing the front part of <I_n>’s sound, which is called a consonant today. The mater <I>, instead of serving to denote the sound(s) of <_n>, was regarded as representing the rear part of <I_n>’s sound, which is called a vowel today.

In Table 21.4 below the sound of <I_n> is represented by a rectangle comprising two parts that are the same shade of light grey. The two parts are the same shade because the functions of the two letters <_n> and <I> had changed. Instead of <I> serving as a mater to denote the sounds of <_n>, both <_n> and <I> now directly represented the two segments of the sound of <I_n>. In other words, as far as sound representation is concerned, <I> can be considered to be on a par with <_n>. Hence the sound segments they represented are the same shade of light grey.

The sound of <I> lasts longer than that of <_n>, and thus <I> is represented by the greater part of the rectangle for the sound /ni/, as shown in the second row of the table. Since <I> represents the rear part of the sound, <_n> naturally represents the front part. The sound of <_n>, by itself, is less prominent and not as long-lasting as the sound of <I>. Hence it takes up the lesser part of the rectangle. It should be noted that the Greeks did not have to heed the sound durations of <_n> and <I>. They did not have to know when exactly the sound of <_n> ended and when the sound of <I> began. All they needed to know was that the sound of <I> followed the sound of <_n>.

Previously, <_n> had been a syllabic sign with multiple sound values, whereas <I> had been a mater. Now to the Greeks, <I> represented the rear part of the sound of <I_n>. The syllabic sign <_n> would thus be reduced to a sign representing only the front part of the sound. Subsequently <_n> would change from a syllabic sign into a consonant letter.

Our explanation of the transformation of the sign <_n> can be said to be fairly close to what I.J. Gelb means by the principle of reduction (1952: 183). Unfortunately, Gelb did not further elaborate on this point. Possibly partly for this reason, other linguists do not seem to have taken the principle of reduction very seriously.

With the vowel and consonant letters in place, Greek writing had at last transformed from a syllabic system to a segmental one. However, the forms of all the letters, including the matres, remained the same throughout the transformation period. Outwardly, nothing seemed to have changed. What had changed was the Greeks’ perception of the functions of the letters, which led to a change in the nature of the letters. The change of the inner structure of Greek alphabetic writing from a syllabic system to a segmental one is not easily discerned. This could possibly be one of the reasons why the origin of the Greek alphabet has not been satisfactorily explained for so long. This change of the nature of Greek alphabetic writing is of enormous significance in the history of writing. It has given rise to a new writing system—segmental writing. Thanks to Greek segmental writing, mankind was able for the first time to split a syllable into its component parts—a consonant and a vowel.

With five vowel letters and less than twenty consonant letters, the Greeks could write quite accurately all kinds of syllable structure in their language, such as V (including monophthongs and diphthongs), VC, and CCV. They would re-examine the existing written words and, if necessary, re-spell them for a more refined and accurate representation of the sound segments of the words. When writing a word not yet written before, they could analyse its sound segment by segment and then write out the segments with the appropriate Greek letters. To be able to write the sound of a word in this way must have been a novel and thrilling experience for the Greeks. Take for example the written representation of the syllable /nai/. In proto-Greek alphabetic writing the Greeks would probably write /nai/ as <A_n>, as they had not yet been able to write diphthongs accurately with the matres they then had (see Table 14). Now that they could write /nai/ out segment by segment as <IAN>, they must have felt that the new written form <IAN> was a significant improvement over the old one <A_n> for the syllable /nai/.

3 February 2017

Views: 623