13 The creation of new vowel letters in early Greek alphabetic writing

When the five matres became vowel letters, what were their sound values in the scripts? If one were to disregard vowel length, <A>, <I>, and <Y> would each represent one vowel quality in all Greek regions while <E> and <O> would each represent two vowel qualities in many Greek regions. In regions where the dialect had the following seven vowel qualities /a, i, u, e, o, ɛ, ɔ/, <E> and <O> would each represent two vowel qualities: <E> would represent both /e/ and /ɛ/, and <O> both /o/ and /ɔ/.

In regions where <E> and <O> each represented two vowel qualities, there was a need to create two more vowel letters so that each vowel letter could neatly represent one vowel quality. However, the need was not so urgent as to make the creation of two more vowel letters obligatory, for a Greek alphabetic script could still function quite well even when <E> and <O> each represented two vowel qualities. /e/ and /ɛ/ could simply be written as <E>, and /o/ and /ɔ/ simply as <O>. Reading <E> and <O>, however, would pose a slight problem. <E> would be read as either /e/ or /ɛ/, and <O> as either /o/ or /ɔ/. As was said in §12.2, the ancient Greeks had a habit of reading aloud. When reading aloud an unfamiliar word spelt with such a letter as <E> or <O>, they might hesitate about the sound value of the letter because the letter had two different sound values. Such instances would make it less convenient for them to read aloud.

Regions speaking a dialect with seven vowel qualities were divided as to whether it was necessary to create two more vowel letters. Some regions created two more vowel letters so that each vowel letter could neatly represent one vowel quality, such as the eastern Ionic Dodekapolis; others were content to stick to five vowel letters for writing their dialect with seven vowel qualities, such as Attica.

According to A. Malikouti-Drachman, Old Attic of the fifth century BC had the following twelve monophthongs: /a(:), i(:), u(:), e(:), o(:), ɛ:, ɔ:/ (2007:526). If vowel length is discounted, Old Attic can be said to have seven vowel qualities. It is also stated in the article on the Greek language in the Encyclopaedia of Britannica (15th edition) that the above vowel system “may be attributed to Old Attic of about 500 BC” (2003: vol. 22, p. 615). If Old Attic had seven vowel qualities, then the sound values of the five vowel letters in the Attic inscriptions of archaic Greece were probably as follows: <A> /a(:)/, <I> /i(:)/, <Y> /u(:)/, <E> /e(:), ɛ:/, <O> /o(:), ɔ:/. <E> and <O> each represented two vowel qualities. As a matter of fact, the Athenians kept on using their alphabet with only five vowel letters until 403 BC when they voted to replace it with the eastern Ionic alphabet of Miletus with seven vowel letters. When Attic was written in the Milesian alphabet, the sound values of the seven vowel letters were: <A> /a(:)/, <I> /i(:)/, <Y> /u(:)/, <E> /e(:)/, <O> /o(:)/, <H> /ɛ:/, <Ω> /ɔ:/. Each vowel letter neatly represented one vowel quality.

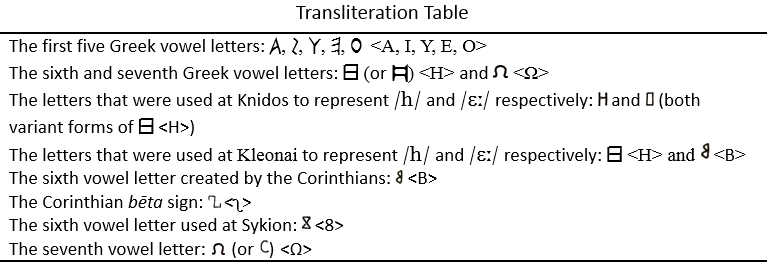

The fact that seven vowel letters were used in the inscriptions of the eastern Ionic Dodekapolis suggests that the eastern Ionic dialect most likely had seven vowel qualities. The sixth and seventh vowel letters in the alphabets of the Ionic Dodekapolis were <H> and <Ω>. How were these two vowel letters created?

13.1 The creation of the sixth vowel letter in Greek alphabetic writing

The sixth vowel letter <H> was derived from the Phoenician sign <_ḥ> ḥēth. Its name was pronounced /hɛ:ta/ in many Greek regions, but in regions where /h/ had disappeared, it was pronounced /ɛ:ta/. In a region where <H> was called /ɛ:ta/, <H> could be used as a vowel letter to represent /ɛ:/ for the following reason. When early Greek alphabetic writing became segmental, a letter in the Greek alphabet would generally represent the initial sound or segment of its name. For example, the letter <A> would represent /a(:)/, which is the initial sound or segment of its name alpha. This is the so-called acrophonic principle. By applying this principle, the Greeks could then use <H> to represent the vowel /ɛ:/, which is the initial sound or segment of its name ēta. Now that <H> represented /ɛ:/, <E> could represent only /e(:)/. While <H> was called /ɛ:ta/, <E> was probably called the /e(:)/ sign.

From Inscriptions 1a, 1a–b, 1, and 1 on Plates 59, 61, 63, and 67 respectively of The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece (Jeffery 1961: at end), one can see that <H> was used as a vowel letter for /ɛ:/ in Thera and in Rhodes as early as the late eighth century BC and in Crete and in Samos more than half a century later in the second half of the seventh century BC. In Thera and in Rhodes the letter <H>, besides representing /ɛ:/, was also used as a consonant letter for /h/, whereas in Crete and in Samos <H> was used exclusively as a vowel letter since /h/ had been lost in the Cretan and Samian dialects. Under these circumstances, it seems more likely that the sixth vowel letter <H> was first created in Crete or Samos than in Thera or Rhodes, because, while one can use the acrophonic principle to account for the creation of <H> as a vowel letter in Crete or Samos, it is more difficult to explain how <H> could evolve into a vowel letter in Thera or Rhodes when it had to represent /h/ at the same time. We believe that it is possible that the sixth vowel letter <H> was first created in Crete or in Samos in the eighth century BC even though it is first attested in the Cretan and Samian inscriptions dated to the seventh century BC. In the history of writing it is not unusual that a lapse of time might occur between the creation of a sign in a place and the first attestation of its existence in that place. It is possible that Thera and Rhodes adopted the use of <H> as a vowel letter from Crete or Samos in the eighth century BC.

Besides Thera and Rhodes, many other Greek regions used <H> to represent both /ɛ:/ and /h/, such as the central and northern Aegean islands (Ionic), Knidos, and Kleonai. In other words, <H> was used both as a vowel letter and as a consonant letter in these regions. Only a few Greek regions went one step further by using <H> and its variant form to represent /h/ and /ɛ:/ respectively. From Inscriptions 31-34 on Plate 68 of The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece, one can see that at Knidos, an ancient Greek city not far away from Rhodes, two variant forms of <H> were used to represent /h/ and /ɛ:/ respectively in the sixth century BC. And from Inscriptions 5-7 on Plates 24-25 of The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece, one can see that at Kleonai, an ancient Greek city not far away from Corinth, the letters <H> and <B> were used to represent /h/ and /ɛ:/ respectively in the sixth century BC. Can one say that just as two variant forms of <H> were used to represent /h/ and /ɛ:/ respectively at Knidos, so <H> and <B> were used to represent /h/ and /ɛ:/ respectively at Kleonai? Is <B> a variant form of <H>?

Kleonai probably adopted the use of <B> as a vowel letter from its powerful neighbour Corinth. In the eighth century BC, Corinth was a flourishing commercial centre. There was a real need for a Greek script to keep administrative and trading records there. The newly-created Greek segmental alphabet that spread from region to region during the eighth century BC must have been most welcome at Corinth when it had arrived there. Judging from the archaic Corinthian inscriptions, the Greek alphabet that Corinth received seems to be an eastern alphabet (see §14). What makes the Corinthian alphabet distinct from the parent alphabet is its use of both <B> and <E> as vowel letters for mid front vowels. <B> seems to be the sixth vowel letter created by the Corinthians. How was it created? What exactly were the sound values of <B> and <E>?

According to Jeffery, at Corinth <B> was “employed for normal ε and η” while <E> was “used for the false diphthong ει only” (1961:24). By this statement Jeffery probably means that at Corinth <B> represented /e/ and /ɛ:/ while <E> represented the monophthong /e:/ that had evolved from the diphthong /ei/. The Greek scholar J. M. Dosuna, however, says that at Corinth “standard epsilon represents short [e] and primary long open [ɛ:]” and that “a special letter (Corinthian epsilon) is used for secondary long close [e:] (resulting from lengthening and contraction, and from the monophthongization of [ei] <ει>)” (2007:447). If by “standard epsilon” and by “a special letter (Corinthian epsilon)” Dosuna means <E> and <B> respectively, then Dosuna seems to be saying in his statement that <E> represents /e/ and /ɛ:/ while <B> represents /e:/. Dosuna’s statement about the sound values of <E> and <B> seems to be at variance with Jeffery’s. Whose statement is correct?

As regards Dosuna’s statement, it should be noted that in the Corinthian inscriptions <B> was used much more frequently than <E>. This means that the vowel(s) represented by <B> occurred much more frequently than the vowel(s) represented by <E>. This is an important point to bear in mind when one talks about the sound values of <B> and <E>. It is unlikely that in the Corinthian inscriptions <E> represented /e/ and /ɛ:/ while <B> represented /e:/, because had this been the case, <E> should have occurred much more frequently than <B> in the Corinthian inscriptions.

Regarding Jeffery’s statement about the sound values of <E> and <B>, we have some queries. If it is true that <B> represented /e/ and /ɛ:/ while <E> represented /e:/, then this implies the following. First, discounting vowel length, <B> represented two vowel qualities (/e/ and /ɛ/) while <B> and <E> represented the same vowel quality (/e/). Second, the creation of the sixth vowel letter <B> had not helped to improve Greek spelling because on the one hand the Corinthians would still have to rely on the context to decide whether <B> should be read as /e/ or /ɛ:/ and on the other they would have to decide whether to use <B> or <E> when writing a sound with the vowel quality /e/. One cannot help wondering why the Corinthians had not made better use of the sixth vowel letter <B> so that <B> and <E> could each neatly represent one vowel quality. Is it possible that the short /e/ and the primary long open /ɛ:/ differed so little in quality that they were considered by the Corinthians to be the same vowel quality? Should this be the case, the short /e/ could be transcribed as the more open /ɛ/, which is distinct from the secondary long close /e:/ that resulted, as Dosuna says, “from lengthening and contraction, and from the monophthongization of [ei]”. If one could reconstruct the vowel system of the Corinthian dialect, one would be able to see more clearly the correlation between its vowels and the six vowel letters in the Corinthian alphabet.

How was the vowel letter <B> created at Corinth? Scholars are divided on this point. Some believe that <B> is a variant of <H>. Some hold that <B> is a variant of <E>. Others say that the Corinthians deliberately and unconventionally used a redundant variant of the bēta sign as a vowel letter. We now comment on these opinions one by one.

Some scholars attribute the creation of the sixth vowel letter <B> to the employment of a variant of <H>. The Corinthians probably knew that <H>, besides representing /h/, was also used as a vowel letter for the mid front vowel in some Greek regions. To disambiguate the function of <H>, the Corinthians used <H> only as a consonant letter for /h/ and its variant <B> only as a vowel letter for the mid front vowel. The first question that arises from this hypothesis is: could <B> be regarded as a derivation of <H> in shape? On the face of it they do not look very much alike, but even so, one cannot deny that there is a sort of family resemblance between them and that <B> could have derived from <H>. The variant of <H> could be written as <B> without being mistaken for the bēta sign because the bēta sign was written in the Corinthian alphabet as <ʅ>, which seems to have derived from the courtyard sign in Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Some scholars believe that <B> is a cursive variant of the vowel letter <E>. If this hypothesis is correct, then the sixth vowel letter <B> was an original Corinthian creation. <E> and its variant <B> were used as vowel letters for the mid front vowels at Corinth. The first question that arises from this hypothesis is similar to the one posed in the above paragraph: could <B> be regarded as a derivation of <E> in shape after all?

Some scholars think that the Corinthians unconventionally used a redundant consonant letter as a vowel letter to represent the mid front vowel. The bēta sign in the Corinthian alphabet had two forms: <ʅ> and <B>. As the Corinthians used only <ʅ> for /b/, <B> became redundant. Since there was a need to create one more vowel letter for the mid front vowel, some Corinthian or Corinthians had the unconventional idea of using <B> as the sixth vowel letter. The other Corinthians soon followed suit. If this hypothesis is correct, then the Corinthians’ decision to arbitrarily use a consonant letter as a vowel letter was a bold move in the history of segmental writing.

The alphabets of Corinth’s neighbours Megara, Sikyon, and Kleonai are basically identical with that of Corinth. We now focus again on the sixth vowel letter in these alphabets. At Megara as at Corinth, the sixth vowel letter <B> was used much more frequently than <E>, which means that the sound values of <B> and <E> were possibly the same in the two places. By contrast, the sixth vowel letter <B> was used much less frequently than <E> at Kleonai, which means the sound values of <B> and <E> at Kleonai must have been different from those at Corinth and Megara. As regards the sixth vowel letter at Sykion, it was written as <8>, not <B>. This is probably because the bēta sign was written as <B> at Sykion, as in many other places. The Corinthian <B> had to assume another shape at Sykion, which turned it into <8>.

13.2 The creation of the seventh vowel letter in Greek alphabetic writing

It is quite certain how and why the seventh vowel letter was created in Greek alphabetic writing. The seventh vowel letter is <Ω> (or its variant form <C>), which everyone agrees is a variant of <O>. As was said earlier, in Greek regions speaking a dialect with seven vowel qualities but writing in an alphabet with only five vowel letters, the letter <O> represented both /o(:)/ and /ɔ:/. To neatly represent these vowels, some of these Greek regions created the seventh vowel letter <Ω>, such as the eastern Ionic Dodekapolis and three of the Aegean islands Delos, Syros, and Keos. In these regions <O> represented /o(:)/, and <Ω> represented /ɔ:/.

It is not so certain, however, when and where the seventh vowel letter was first created in Greek alphabetic writing. By referring the reader to Guarducci’s Epigrafia greca (1967:101 and 159-60), C. Brixhe says that <Ω> “appears for the first time, at the turn of the eighth and seventh centuries, on a Parian graffto on Delos” (2007:281). If the dating of the Parian graffito is correct, then one can say that the seventh vowel letter <Ω> was first created probably in the eighth century BC, even though one cannot say for certain that it was first created on Paros or Delos, or elsewhere.

In Jeffery’s The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece are collected some of the earliest archaic Greek inscriptions in which the seventh vowel letter <Ω> is attested, such as Inscriptions 61, 2, and 26 on Plates 58, 63, and 56 respectively. The first one is a marble block inscription of the late seventh century BC from Thasos; the second one is a gravestone inscription of the early sixth century BC from Samos, and the third one a marble column inscription of the first half of the sixth century BC from Paros. It seems that many Greek regions came to use the seventh vowel letter <Ω> for the first time much later than the eighth century BC.

It should be noted that the seventh vowel letter <Ω> had different sound values in different Greek regions. As has just been said, in the eastern Ionic Dodekapolis and on three of the Aegean islands Delos, Syros, and Keos, <O> represented /o(:)/ while <Ω> represented /ɔ:/. In these regions, <O> was probably called the /o(:)/ sign, and <Ω> the /ɔ:/ sign. However, on Thasos and Paros, <O> and its variant <Ω> swapped their sound values: <O> represented /ɔ:/ while <Ω> represented /o(:)/. In these regions, <O> was probably called the /ɔ:/ sign, and <Ω> the /o(:)/ sign. It is possible that the names of <O> and <Ω> determined their sound values.

In Melos, Sikinos, Anaphe, and Knidos, the letter <O> and its variant <C> (a half circle) were used to represent /ɔ:/ and /o(:)/ respectively. In these regions, <O> was probably called the /ɔ:/ sign, and <C> the /o(:)/ sign. In Paros and Thasos, the bēta sign happened to be the same shape as <C>; therefore, to avoid confusion with bēta, <C>, a variant of <O>, was turned 90˚ clockwise and, to make it visually more distinct from the other letters, was given two splay feet for it to change into <Ω>. This could possibly account for the shape of <Ω>. Just as <O> and <C> were used to represent /ɔ:/ and /o(:)/ respectively in Melos, Sikinos, Anaphe, and Knidos, so <O> and <Ω> were used to represent /ɔ:/ and /o(:)/ respectively in Paros and Thasos.

5 February 2017

Views: 266