14 The creation of new consonant letters in early Greek alphabetic writing

As explained in §12.5, when the five matres changed into vowel letters, the ordinary Phoenician signs used for writing Greek would inevitably change from syllabic signs into consonant letters. This shift in the nature of Greek alphabetic writing probably took place in the ninth century BC. What were the sound values of the consonant letters of the Greek alphabet when Greek writing had become segmental?

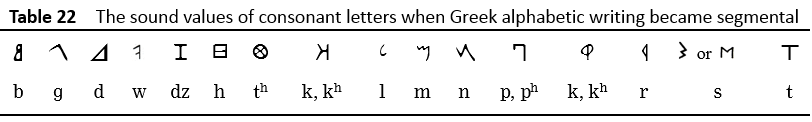

We assume that before Greek alphabetic writing became segmental, the ancient Greeks had already decided to use (1) only <Θ> for /th_/ rather than both <Θ> and <Τ>; (2) only <T> for /t_/ rather than both <Θ> and <T> and (3) only <Σ> or <Μ> (variants of <_ʃ>) for /s_/ rather than <_ʃ>, <_s>, and <_ʔs>. If this assumption is correct, then when Greek alphabetic writing became segmental, the consonant letters would have sound values as shown in Table 22 below:

As can be seen from Table 22 above, although it is generally true that each letter represented one consonant and that each consonant was represented by one letter, there are some exceptions. For instance, the letter <P> represented both /p/ and /ph/ sounds, while the /k/ and /kh/ sounds were each represented by the letters <K> and <Q>. Such instances might pose a slight problem for the ancient Greeks in reading and in writing.

When writing /k/ or /kh/, the ancient Greeks had to choose between <K> and <Q>. This, however, would not pose much of a problem for them because there was a simple rule for them to follow regarding the use of <K> and <Q>. When /k/ or /kh/ was followed by /u(:)/ or /o(:)/, they would use <Q>; otherwise, they would use <K>. This could be the main reason why the ancient Greeks seemed to be quite happy to keep on using both <K> and <Q> for /k/ until the sixth century BC when <Q> was gradually replaced by <K> (see §11.1.1).

When reading aloud an unfamiliar word spelt with such a letter as <P>, <K>, or <Q>, the ancient Greeks might hesitate about the sound value of the letter because the letter had two different sound values: <P> represented both /p/ and /ph/; <K> represented both /k/ and /kh/, and so did <Q>. Such instances would make it less convenient for the ancient Greeks to read aloud. There was thus a need to represent /p/, /ph/, /k/, and /kh/ more precisely. Judging from the local scripts of archaic Greece, the ancient Greeks except the Cretans did take the trouble to create more graphemes so as to represent /k/, /kh/, /p/, and /ph/ more precisely. The Cretans did not seem to mind very much that <P>, <K>, and <Q> each had two sound values. They went on using <P> for /p/ and /ph/ and <K> for /k/ and /kh/ until the fourth century BC when all the Greek regions came to adopt the Milesian alphabet as the standard. As for <Q>, the Cretans used it also for /k/ and /kh/, but replaced it with <K> in the sixth century BC.

14.1 The creation of the new digraphs for /ph/ and /kh/ in Thera

To the ancient Greeks, /p/, /ph/, /k/, and /kh/ were four different sounds. They might not know, however, how these sounds were different. Judging from the way in which /ph/ and /kh/ were written in ancient Thera, these sounds had been analysed and found to be aspirated. Inscriptions 1a(i) and 5 on Plate 61 in The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece (Jeffery 1961: at end) show that in ancient Thera, while /p/ and /k/ were written as <P> and <K> respectively, /ph/ and /kh/ were written as <HP> and <HK> respectively (for simplicity’s sake, <Q>, the alternative of <K>, is ignored from now on). In <HP> and <HK>, <H> represented the aspirate sound /h/. As Inscription 1a(i) on Plate 61 is dated to the end of the eighth century BC, the Therans had probably learned to write /ph/ and /kh/ as <HP> and <HK> at a date earlier than 700 BC.

The Theran method of writing /p/, /ph/, /k/, and /kh/ probably implies the following: (1) As /p/, /ph/, /k/, and /kh/ were four different sounds, the Therans wanted to represent them differently in writing. (2) When Greek alphabetic writing became segmental, the ancient Greeks would come to realize that different letters generally represented different segments or sounds. By focusing on the sound represented by a consonant letter, they would be able to grasp better and better the nature of this sound. With the accumulated knowledge of the nature of the sounds represented by the Greek consonant letters, the Therans could set about analysing the sounds of /p/ and /ph/ to see how they were different. Eventually they would come to realize that /p/ was unaspirated, while /ph/ was aspirated. They might reason that if they could write /p/ as <P>, then they could write /ph/ as <HP>, because the aspirate sound could be represented by the letter <H>, which they used for /h/. The Therans hence used <P> for /p/ and <HP> for /ph/. By analogy, they used <K> for /k/ and <HK> for /kh/. It may be noted that the Therans’ method of notating /ph/ and /kh/ over 2500 years ago is basically the same as the one used by the International Phonetic Association today.

The Theran method of writing /p/, /ph/, /k/, and /kh/, scientific as it is, has some shortcomings. <HP> could be read as /ph/, but it could also be read as /pɛ:/, because <H> could also be used in Thera as a vowel letter for /ɛ:/. Thus the Therans had to rely on the context to decide on the sound value of <HP>. Similarly, <HK> could be read as /kh/ or /kɛ:/. It can be said that the Therans’ solution to a problem gave rise to another problem. This phenomenon is by no means rare in the evolution of writing.

The use of <HP> and <HK> for /ph/ and /kh/ is also attested in Inscription 23 on Plate 62 dated to the late sixth century BC from Melos, an island not far away from Thera. It seems that the Theran method of writing /ph/ and /kh/ had spread to Melos during the seventh or sixth century BC.

14.2 The creation of two more letters for /ph/ and /kh/

While Thera managed to represent /p/, /ph/, /k/, and /kh/ differently in writing without creating a new letter, the eastern and western Greeks created two more letters so that these four sounds could each be neatly represented by a distinct letter. To neatly represent /p/, /ph/, /k/, and /kh/, the eastern Greeks used <P>, <Φ>, <K>, and <Χ> while the western Greeks used <P>, <Φ>, <K>, and <ψ>, respectively.

To represent /ph/, both the eastern and western Greeks exploited <Φ>, which we believe is a variant of the Greek letter <Q> qōppa that evolved from the Phoenician sign <_q> qōph. That so many different regions arbitrarily employed the same sign <Φ> for /ph/ probably bespeaks a single source. Because of the arbitrary relationship between the letter <Φ> and the sound /ph/, the numerous Greek city-states could not have created <Φ> to represent /ph/ independently of each other.

When Greek writing became segmental, the Greeks would come to regard a consonant letter as representing the first consonant or sound of its name. For example, the letter <B> represented /b/, which is the first sound of its name bēta. The name bēta originates from the name of the Phoenician sign <_b> bēth. The name bēth, meaning ‘house’ in Phoenician, reminds the Phoenicians that the sign <_b> originally depicts a house. Even though <_b> is not very pictorial, its shape is somehow bound by the meaning of its name bēth as it evolves. However, when the name became bēta in Greek, it had lost its original meaning. To the Greeks, bēta was just the name of a letter. The shape of the letter bēta was thus free to evolve in Greek writing, so long as it remained distinct from the other letters. Thus generally speaking, the relation between the shape of a Greek letter and the sound it represented became more and more arbitrary.

It is possible, therefore, that when some Greek had the bold or unconventional idea of using <Φ> for /ph/, the other Greeks did not find it objectionable in principle to use <Φ> in this way. What bothered them would be that the new letter <Φ> should look distinct from <Q> qōppa. Once they were assured that the two letters were distinct, the idea of using <Φ> for /ph/ would catch on as it had met the need for a new letter for /ph/. The Greeks would then give the new letter a name with the initial sound /ph/, say, phi /phi/. The Greeks would come to realize that any new letter, when given a name that complied with the acrophonic principle, could be used to represent the initial sound of that name as long as it was distinct from the existing letters. In other words, the choice of this letter could be arbitrary. This was no ordinary discovery in the history of writing, which one tends to lose sight of today. Equipped with this piece of knowledge, the Greeks could, in theory, write any Greek phoneme that did not exist in Phoenician, be it a vowel or a consonant.

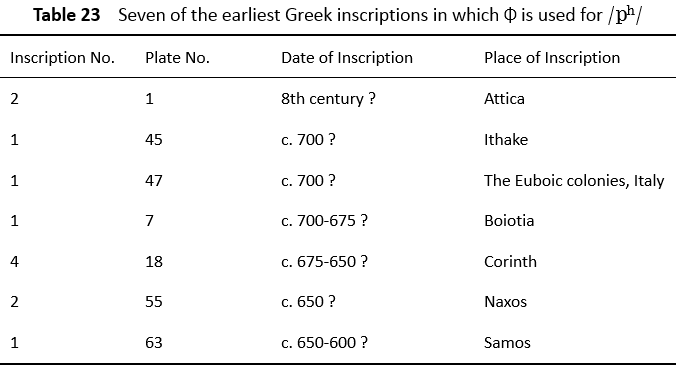

As can be seen from the archaic Greek inscriptions published in Jeffery’s The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece, the use of <Φ> for /ph/ was widespread in ancient Greece. To find out where and when the new letter <Φ> was first created, one can only resort to the earliest inscriptions of the Greek regions in which <Φ> is used for /ph/ and hazard a guess. To this end, some relevant bits of information about seven such inscriptions are listed in Table 23 below:

Judging from the above table, the letter <Φ> was first created for /ph/ probably in the eighth century BC, possibly in Attica in Central Greece. If this hypothesis is correct, one may say that the idea of using <Φ> for /ph/ spread from Attica both eastwards and westwards and won the approval of the Greeks everywhere except those living on the southernmost islands in the Aegean Sea such as the Cretans and Therans.

As for the representation of /kh/, the eastern and western Greeks employed different letters. The eastern Greeks arbitrarily chose <X> or <+>, which we believe is a variant of <T> tau, while the western Greeks used <ψ>, which we believe is a variant of <K> kaph. The new letter <X> or <ψ> used for /kh/ would be given an appropriate name, say, khi /khi/, and with an appropriate name <X> or <ψ> could be used to represent /kh/.

The use of <X> for /kh/ is analogous with the use of <Φ> for /ph/. Just as the letter <Φ> used for /ph/ had to be distinct from the letter <Q> used for /k(h)/, so the letter <X> used for /kh/ had to be distinct from the letter <T> used for /t/.

The use of <ψ> for /kh/ is analogous in a sense with the use of <Ω> for /ɔ:/. Just as the vowel letter <O> and its variant <Ω> were used to represent /o(:)/ and /ɔ:/ respectively, so the consonant letter <K> and its variant <ψ> were used to represent /k/ and /kh/ respectively.

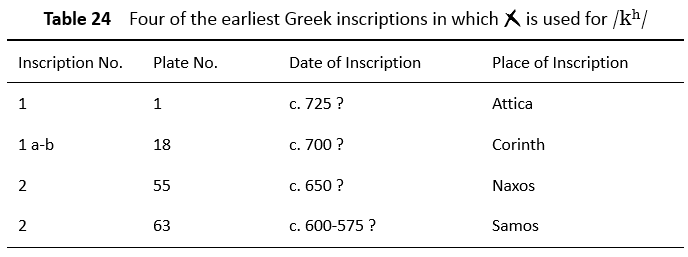

To find out where and when <X> was first used for /kh/, one has to resort to the earliest Greek inscriptions in which <X> is used for /kh/. We refer again to some of the earliest inscriptions published in The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece. Some relevant bits of information about four such inscriptions are listed in Table 24 below:

Judging from Table 24, <X> was first used for /kh/ probably in the eighth century BC, possibly in Attica.

While the choice of <X> for /kh/ is quite arbitrary, the choice of <ψ> for /kh/ is not completely arbitrary. <ψ>, a variant of <K>, was possibly used to represent the Greek /k_/ and /kh_/ at a very early date. This letter had probably become redundant when Greek writing became segmental. As there was a need to represent /k/ and /kh/ more precisely in Greek writing, the idea of employing this redundant letter for /kh/ might come to some Greek. When he used <ψ> to write /kh/, the other Greeks would probably find it a good idea to write /kh/ in this way and so would follow suit.

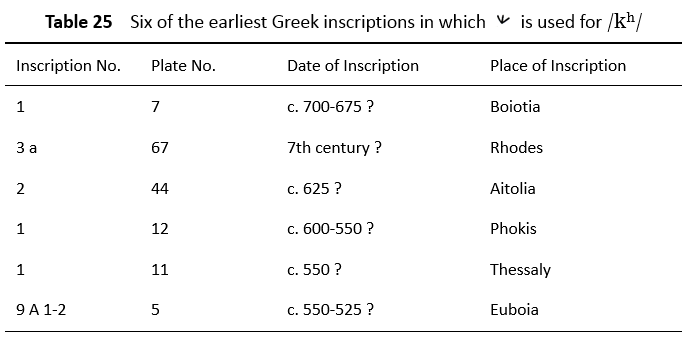

Where and when was <ψ> first used for /kh/? Again we resort to some of the earliest inscriptions published in The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece. See Table 25 below:

Judging from Table 25, <ψ> was first used for /kh/ probably in the eighth century BC, possibly in Boiotia. The idea of using <ψ> for /kh/ possibly spread from Boiotia to the neighbouring regions such as Euboia, Thessaly, Aitolia, and Achaia.

14.3 The creation of two more letters for /ks/ and /ps/

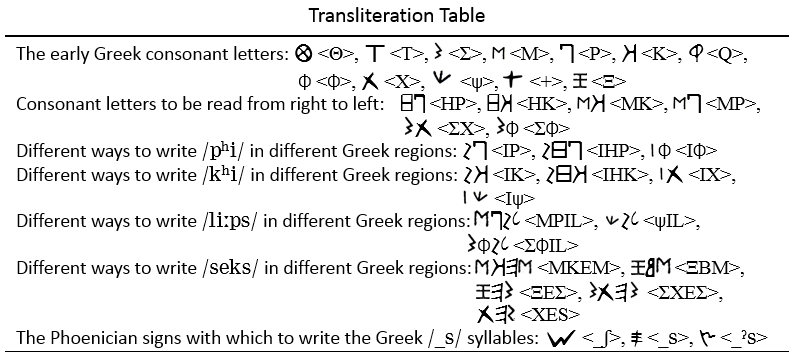

How the ancient Greeks represented the consonant clusters /ks/ and /ps/ in writing is also noteworthy. When Greek writing became segmental, each of these clusters could well be represented by two consonant letters―one letter for /k/ or /p/, and the other for /s/. It is small wonder that so many Greek regions used two consonant letters to represent them. Some regions used <K> for /k/, <P> for /p/, and <M> for /s/, while some others used <X> for /kh/, <Φ> for /ph/, and <Σ> for /s/. It seems that the two consonant clusters were perceived as /ks/ and /ps/ by some Greeks and as /khs/ and /phs/ by others. Consequently, the clusters were written as <MK> and <MP> in some regions and as <ΣX> and <ΣΦ> in others. It is possible that the clusters were spoken either as [ks] and [ps] or as [khs] and [phs]. [khs] and [phs] were possibly a more formal way of speaking than [ks] and [ps]. When the clusters were spoken as [ks] and [ps], the aspirate sound was elided to reduce the effort of speaking.

While many Greek regions used two letters to represent /ks/ and /ps/, many other regions, however, went one step further by arbitrarily choosing one single new letter for each cluster. For example, the Ionic Dodekapolis arbitrarily chose <Ξ> and <ψ> for /ks/ and /ps/ respectively, while Thessaly arbitrarily chose <+> for /ks/. Each of the new letters would be given an appropriate name. <Ξ> and <+> might be called ksi /ksi/, and <ψ> psi /psi/.

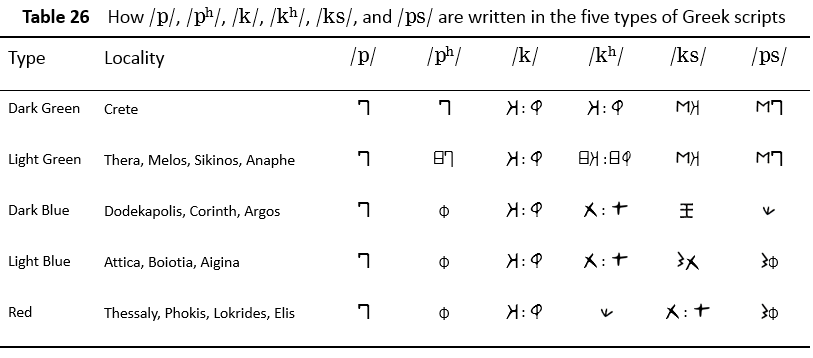

The local scripts of archaic Greece can be classified according to how /p/, /ph/, /k/, /kh/, /ks/, and /ps/ are written. This is basically the idea of the German classical scholar A. Kirchhoff, who labelled the three types of scripts thus classified as “green”, “blue” and “red” on a map of Greece. The “green” type can further be divided into “dark green” and “light green”, and so can the “blue” type. Table 26 below shows the five types of Greek script, the localities where the types were used, and the ways in which /p/, /ph/, /k/, /kh/, /ks/, and /ps/ were written:

As can be seen from the above table, /ph/, /kh/, /ks/, and /ps/ are written differently in different Greek regions. We now use four concrete examples to illustrate this point. If the sound of the English word pea [phi:] were to be written in archaic Greek letters in different Greek regions, it would be written like this: <IP> in Crete, <IHP> in Thera, and <IΦ> in most other city-states (it may be noted that the same letter may assume different shapes in different regions). The sound of the English word key [khi:] would be written like this: <IK> in Crete, <IHK> in Thera, <IX> in Attica, Corinth, and Miletus, and <Iψ> in Thessaly. The sound of the English word leaps [li:ps] would be written like this: <MPIL> in Crete and Thera, <ψIL> in Corinth and Miletus, and <ΣΦIL> in Attica, Boiotia, and Thessaly. The sound of the English word sex [seks] would be written like this: <MKEM> in Crete and Thera, <ΞBM> in Corinth, <ΞEΣ> in Miletus and Samos, <ΣXEΣ> in Attica, and <XES> in Thessaly.

One can see the diversity of the local scripts of archaic Greece from the above four examples. Thus the city-states needed to adopt a standard alphabet if they wanted to communicate with one another more efficiently in writing. From around 400 BC onwards, the Greek city-states gradually came to adopt the Milesian alphabet as the standard alphabet. By 350 BC the Milesian alphabet had evolved into the classical Greek alphabet of 24 letters that was used in common by all the Greek city-states. The names of the letters all conform to the acrophonic principle: a letter in the alphabet basically represents the initial phoneme or sound of its name. The classical Greek alphabet is nearly phonemic, as one letter basically represents one phoneme.

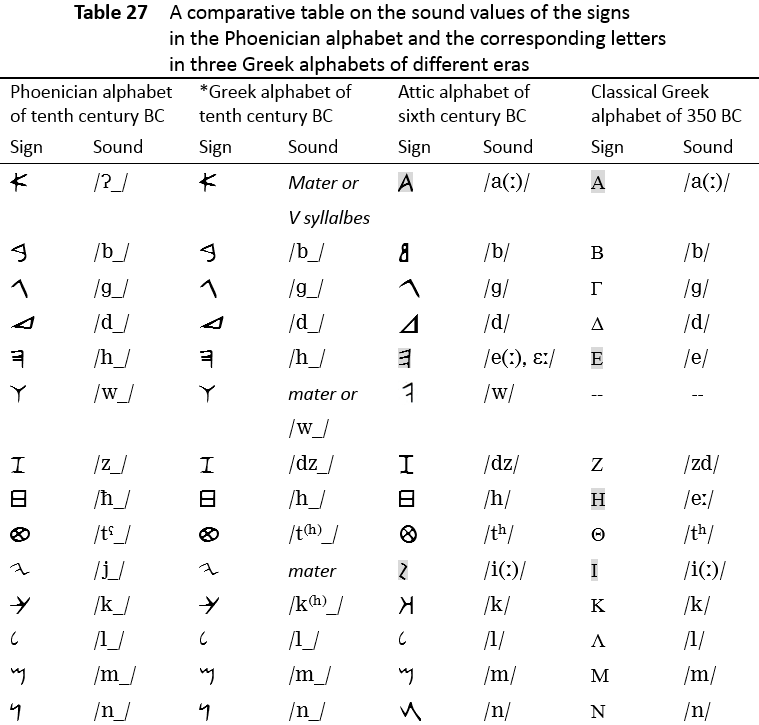

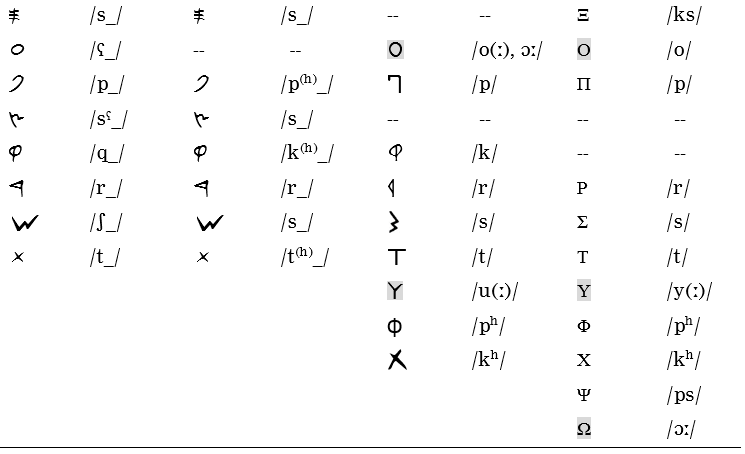

Table 27 below is a comparative table on the sound values of the signs in four alphabets―the Phoenician alphabet of the tenth century BC, a hypothetical Greek alphabet of the tenth century BC, the Attic alphabet of the sixth century BC, and the classical Greek alphabet of 350 BC which evolves from an eastern Ionic alphabet.

By comparing the sound values of the signs in one alphabet in Table 27 with those of the corresponding signs in the alphabet in the next column, one can see how in essence Greek alphabetic writing developed in the first millennium BC, and one can come to the following conclusions.

By comparing the sound values of the signs in one alphabet in Table 27 with those of the corresponding signs in the alphabet in the next column, one can see how in essence Greek alphabetic writing developed in the first millennium BC, and one can come to the following conclusions.

First, even though the hypothetical Greek alphabet of the tenth century BC is in essence of the same nature as the Phoenician alphabet, there are some important differences. One important difference is that a Phoenician sign represents far fewer CV syllables than the corresponding Greek letter. Another important difference is that matres are used much more persistently and regularly in Greek writing than in Phoenician writing.

Second, even though the letters in the hypothetical Greek alphabet of the tenth century BC and the Attic alphabet of the sixth century BC are more or less the same in outward form, they are in fact drastically different in nature. While a letter in the former alphabet may represent as many as twenty-two CV syllables with a common onset, a letter in the Attic alphabet basically represents only a single vowel or a single consonant.

Third, the classical Greek alphabet of 350 BC with seven vowel letters (highlighted in the table) represents a vocalic system with seven vowel qualities more precisely than the Attic alphabet with five vowel letters (also highlighted in the table).

We believe that among all the local alphabets of archaic Greece, the Cretan alphabet is the closest to the parent alphabet of the ninth century BC when Greek alphabetic writing first became segmental.

6 February 2017

Views: 3590